What is a mortality chart? The answer might seem relatively straightforward, but it turns out to be more involved than it first appears.

First, the easy part.

When understanding complex information, a mortality chart is a powerful tool. This graphical representation allows us to easily visualize death rates for a specific population over time, providing a clear and accurate picture of trends and patterns.

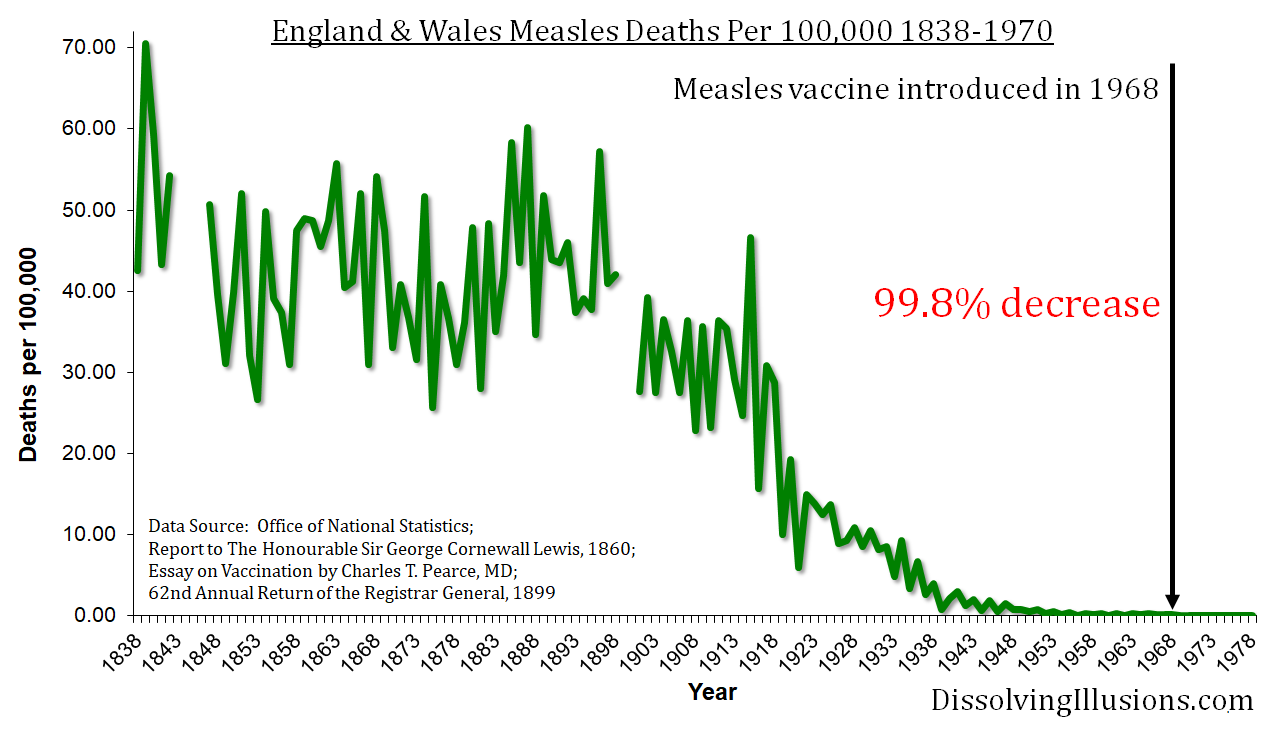

A mortality chart standardizes the data by expressing the death rate typically as the number of deaths per 100,000 individuals. This allows for fair comparison over time, regardless of population size changes. The chart’s vertical y-axis displays the death rate as the number of deaths per 100,000 individuals, and the horizontal x-axis represents the years. With this visual representation, we can quickly and easily identify death rate trends and observe various intervention impacts on death rates over time.

Seems simple. A person dies of a disease. Their death is recorded, and all the numbers are added up. The total for a year is divided by the population to get a fair comparison over time and standardized to deaths per 100,000. In the end, you can see trends over the years. But is it really that simple?

For example, let’s take a closer look at measles mortality rates. National mortality statistics for measles were first compiled in the United States in 1900. The mortality rate is represented on the vertical y-axis as deaths per 100,000 individuals. The horizontal x-axis shows the years beginning in 1900 and ending in 1970. As the years progressed, the chart demonstrates fluctuations in the number of deaths caused by measles, with an overall trend of decreasing deaths over time. The measles injection was introduced in 1963, and as you can see on the chart, the death rate from measles had been reduced by a striking 98.6% from its peak by that time.

We can look at similar data in England. They began to collect data much earlier, in 1838. Here again, we see a massive decline in deaths from measles starting in the late 1800s and plummeting to near zero by 1968 when a vaccine was introduced there. That decline was by almost 100%.

Initially, these charts seem impossible. That’s because we have been taught to think that there is a single microbe that causes death from a disease such as measles. We have also been trained to believe that the vaccine was created, and that’s why we don’t see measles deaths. Yet, we can see in these charts that the vaccine couldn’t have caused such a massive drop in measles deaths since they were introduced well after almost all of the improvements in the death rate had been accomplished.

The way most of us were taught to think about measles deaths is too simplistic and an incorrect way to look at reality. There had to be other factors that made the difference in the decline in the measles death rate.

One significant change from the 1800s to the mid-1900s was the improvement in people’s nutrition. For example, vitamin A has been thoroughly demonstrated to effectively reduce mortality rates and the length of hospital stays.

Combined analyses showed that massive doses of vitamin A given to patients hospitalized with measles were associated with an approximately 60% reduction in the risk of death overall, and with an approximate 90% reduction among infants... Administration of vitamin A to children who developed pneumonia before or during hospital stay reduced mortality by about 70% compared with control children.[1]

Vitamin A administration also reduces opportunistic infections such as pneumonia and diarrhea associated with measles virus-induced immune suppression. Vitamin A supplementation has been shown to reduce risk of complications due to pneumonia after an acute measles episode. A study in South Africa showed that the mortality could be reduced by 80% in acute measles with complications, following high-dose vitamin A supplementation.[2]

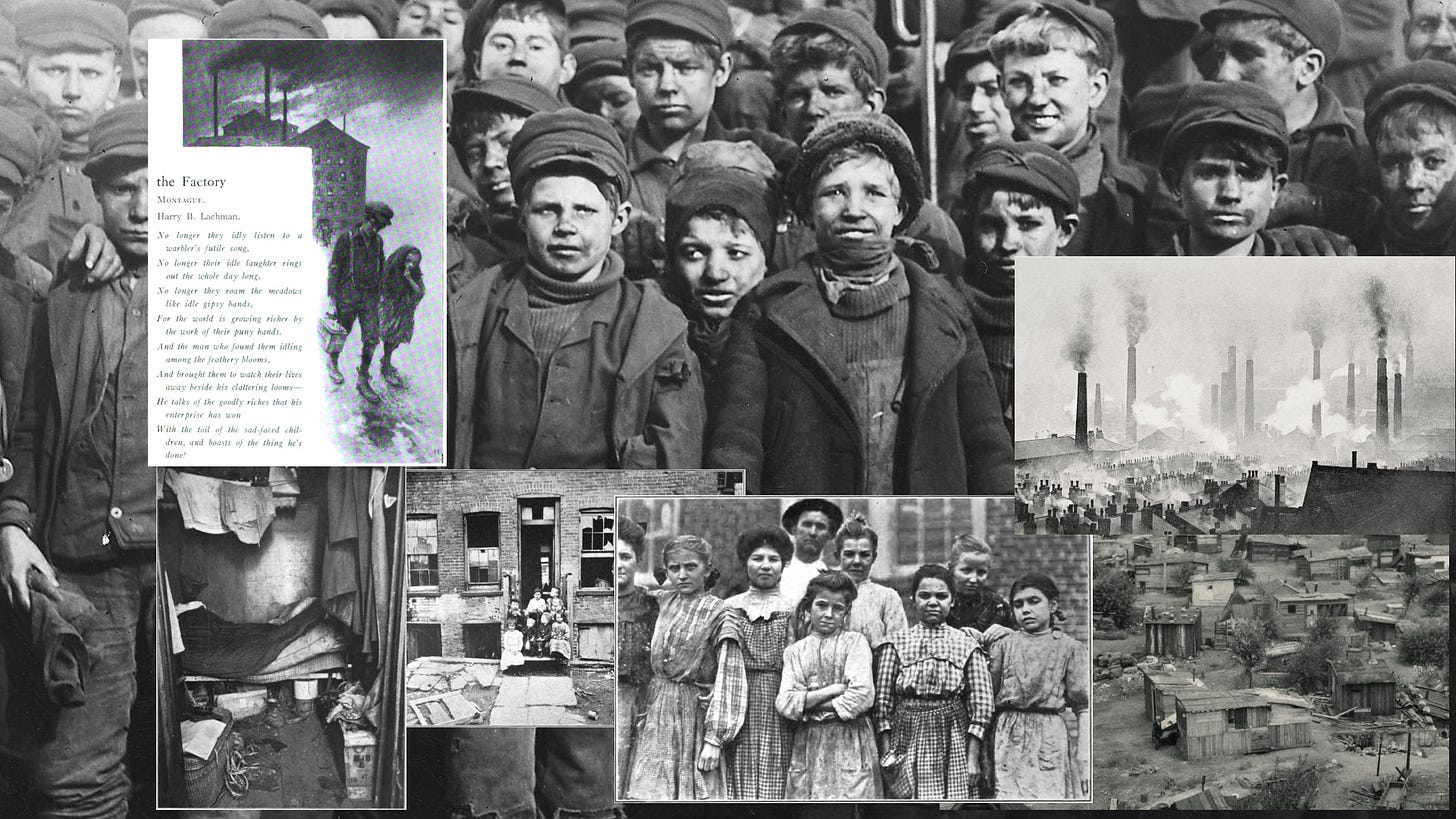

But it’s not enough just to look at vitamin A. Life before the mid-1900s was incredibly tough for both adults and children. Imagine living in homes that were not just dirty, but infested with pests like rats and cockroaches. There were no proper sanitation or clean water systems, so the water people drank was often contaminated with waste and harmful chemicals from factories. Both adults and children, some as young as four years old, had to work for very long hours in terrible conditions. Imagine working in dark, dangerous factories or mines most of your day.

Food was a challenge too. Without refrigeration, much of the food people could access was low quality and often spoiled. Imagine eating rotten food that offered little to no nutrition. To make matters worse, coal was commonly used for heating and powering machines, which led to severe air pollution in many places. The air was thick with smoke and harmful particles, making breathing difficult.

All these terrible conditions took a toll on people’s health. Diseases of all kinds were rampant, and many people didn’t live long lives because of the poor living and working conditions they endured. It was a time of great hardship and suffering for many people.

For millions, entire lives—albeit often very short ones—were passed in new industrial cities of dreadful night with an all too typical socio-pathology: foul housing, often in flooded cellars, gross overcrowding, atmospheric and water-supply pollution, overflowing cesspools, contaminated pumps, poverty, hunger, fatigue and abjection everywhere. Such conditions, comparable to today’s Third World shanty town or refugee camps, bred rampant sickness of every kind. Appalling neonatal, infant and child mortality accompanied the abomination of child labour in mines and factories; life expectations were exceedingly low—often under twenty years among the working classes—and everywhere sickness precipitated family breakdown, pauperization and social crisis.[3]

A 1913 Massachusetts Child Labor Committee report describes the difficult working conditions and the effects on children.

It [work] is done in close, poorly-ventilated rooms, often in dirty kitchens and in unhygienic houses... The children work long hours and often late at night by lamplight. Small children of five, seven, and nine years of age work in a bending position until nine or ten o’clock. This is bad for the eyes, causes nervous strain, interferes with the child’s schooling. The anemic, tired, nervous, overworked children are driven until they cry out against the abuse... A girl seven years old had worked sitting in the hot sun while she was sick with measles. The lack of care at that time was followed by her death...[4]

[A peek at life in the 1800s and early 1900s]

Yet, over the 1800s, the seeds of positive change were sowed and slowly took root. It was the beginning of the world’s greatest health revolution. Clean water infrastructure with pipes and sewers, hand washing, eliminating slums, moving industries away from housing, improved food handling, vastly improved nutrition, labor, and child labor laws, public schools replacing child labor, proper rest, electricity, refrigeration, transportation, the flush toilet, other scientific advancements, mitigating horrible air, water and land pollution, and other factors, radically changed the environment and thus the health of the people.

Accordingly, the present generation is beginning to learn and will realize more thoroughly as time wears on that the fatalistic idea with regard to contagious and infectious disease is absolutely erroneous and that many so-called unavoidable diseases are positively preventable. It is not true each individual must run the gamut of measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, diphtheria, tuberculosis and the like if proper precautionary measures be taken at the outset. Sunshine, fresh air, wholesome nutrition, exercise, rest and the hygienic mode of living are far more effectual than all the subsequent medication in existence.[5]

So, it was a wide variety of factors that resulted in the massive drop in measles deaths as well as other diseases like whooping cough, scarlet fever, and tuberculosis. These diseases all declined simultaneously without any medical interventions like vaccines or antibiotics. In fact, the faulty medical notions of the time contributed to a considerable number of deaths that would have sometimes been counted as the diseases they were attempting to treat.

During this era, numerous conventional medical beliefs and practices embraced by medical men had the very real potential to be lethal. These medical men of the time wielded a range of toxic medications, including calomel (mercury), phosphorus, strychnine, opium, laudanum (opium and alcohol), arsenic, cyanide, chloral, morphine, and jalap (a potent purgative), among others, as essential tools in their medical arsenal.

For upwards of twenty-three centuries to starve, bleed, purge, and torture, had been the all but exclusive business of the man of medicine. From the days of Hippocrates till within the last few years, this was the undoubted practice in almost all diseases.[6] — Samuel Dickson, MD

Mankind has been drugged to death, and the world would be better off if the contents of every apothecary shop were emptied into the sea, though the consequences to the fishes would be lamentable. The disgrace of medicine has been that colossal system of self-deception, in obedience to which mines have been emptied of their cankering minerals, the entrails of animals taxed for their impurities, the poison-bags of reptiles drained of their venom and all the inconceivable abominations thus obtained thrust down the throats of human beings suffering from some fault of organization, nourishment or vital stimulation.[7] — Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes

How often are we disappointed in our expectations from the most certain and powerful of our remedies, by the negligence or obstinacy of our patients! What mischief have we done under the belief of false facts (if I may be allowed the expression) and false theories! We have afflicted in multiplying diseases. – We have done more – we have increased their mortality.[8] — Benjamin Rush, MD

The science of medicine is barbarous jargon, and the effects of our medicines on the human system are in the highest degree uncertain, except that they have already destroyed more lives than war, pestilence and famine combined.[9] — Dr. John Mason Good

There was more quackery in the profession than out of it; and I declare it to be my most conscientious opinion, that if there were not a single physician, or surgeon, or apothecary, or druggist in the world, there would be less mortality among mankind than there is now.[10] — Sir William Johnson

More harm than good has been done by the use of drugs in the treatment of measles, scarlatina, and other self-limited diseases.[11] In their zeal to do good, physicians have done much harm. They have hurried thousands to the grave who would have recovered if left to nature.[12] — Professor Alonzo Clark, MD

Among history’s most renowned infectious diseases stands smallpox, a sickness often regarded as dangerous, claiming the lives of one in every five afflicted individuals. However, throughout history, some doctors documented that smallpox might not be the overwhelmingly fatal disease it was generally believed to be. Instead, smallpox appeared to be a mild ailment when appropriately managed and not mishandled.

…from all the observations that I can possibly make, that if no mischief be done, either by physician or nurse, it [smallpox] is the most slight and safe of all other diseases.[13] — Thomas Sydenham, MD, 1688

A natural simple small-pox seldom kills, unless under very ill-management, or when some lurking evil that was quiet before is roused in the fluids and confederated with the pocky ferment.[14] — Isaac Massey, Apothecary to Christ’s Hospital, 1727

I consider even the Natural Small-pox a mild disease, and only rendered malignant by mistakes in nursing, in diet, and in medicine, and by want of cleanliness…[15] — John Birch, MRCS, 1814

It [smallpox] is a most harmless disease if properly treated. I have treated hundreds of cases without a single fatality.[17] — Dr. Smiley, Matlock, Bath, 1907

Could these doctors have been right? Was smallpox a mild disease made worse by not only the general health of the people and the environment in which people lived but also by the medical treatment notions of the time?

For 80 years, smallpox was attempted to be stopped by inoculation, which was taking pus from a smallpox sore and scratching it onto a healthy person. This was followed by vaccination, which was basically the same thing, except the pus was taken from a cow, horse, goat, sheep, donkey, buffalo, or other animal. That medical idea continued for over 100 years, failing to stop the plague it had promised to stop.

It wasn’t until every infectious disease deaths began to decline that smallpox deaths too began to decrease.[18] The reason? Vastly improved health and environment and reduced deadly medical interventions, including falling smallpox vaccination rates.

In fact, like every other infectious disease, smallpox became a mild disease of little consequence by the end of the 1800s into the early 1900s.

Smallpox had become a mild illness, with a significant decrease in its fatality rate. The fatality rate of 20.84% in 1895 had dropped to an astonishing 0.26% [98.7% decrease]. [19]

By 1939, in the United States, 72,946 smallpox cases in 1902 fell to 9,877 in 1939 [86.5% decrease], 2,510 smallpox deaths in 1902 fell to 38 in 1939 [98.5% decrease], and the case/fatality rate of 4.24 in 1900 fell to 0.38 in 1939 [91% decrease].[20]

So, was smallpox the deadly disease it has been portrayed as, or was its deadly nature (like every other infectious disease) due to the poor health of the people, the miserable environment they lived in, and the destructive medical practices of the time?

The next time you look at a chart showing causes of death, think about whether it’s just one germ causing a single disease or if there are other hidden reasons behind the numbers that you might not know about. These hidden factors can change what the chart really means and the illusion you may have been living under.

[1] Wafaie W. Fawzi, MD; Thomas C. Chalmers, MD; M. Guillermo Herrera, MD; and Frederick Mosteller, PhD, “Vitamin A Supplementation and Child Mortality: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of the American Medical Association, February 17, 1993, p. 901.

[2] Prakash Shetty, Nutrition Immunity & Infection, 2010, p. 82.

[3] Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, Harper Collins, New York, 1997, p. 399.

[4] Child Labor in Massachusetts Tenements, Annual Report of the Massachusetts Child Labor Committee, January 1, 1913, pp. 5–6.

[5] Author unknown, Oral Hygiene, vol. 1, no. 1, January 1911, pp. 183–184.

[6] Samuel Dickson, MD, Glasgow, The “Destructive Art of Healing;” or, Facts for families, Second Edition, 1855, London, pp. 5-6.

[7] “Honest Confessions of Weakness,” Journal of Osteopathy, vol. IV, no. 5, October 1897, Kirksville, Missouri, p. 228.

[8] Benjamin Rush MD, Professor of Chemistry University of Pennsylvania, Medical Inquiries and Observations, Second Edition, 1789, pp. 47-48.

[9] Thomas R. Hazard, Civil and Religious Persecution in the State of New York, 1876, Boston, p. 102.

[10] A New Year's Gift to the Lord Provost, Magistrates, and Town Council of the City of Glasgow, 1st January, 1874. p. 45.

[11] Thomas R. Hazard, Civil and Religious Persecution in the State of New York, 1876, Boston, p. 105.

[12] Emmet Densmore MD, How nature cures, comprising a new system of hygiene, 1892, p. 205.

[13] R. G. Latham, MD, The Works of Thomas Sydenham, MD, vol. I, 1848, London, pp. lxxii-lxxiii.

[14] Isaac Massey, Remarks on Dr. Jurin’s Last Yearly Account of the Success of Inoculation, 1727, London, p.5.

[15] The Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1814, p. 24

[16] The Public, Chicago, Saturday, August 27, 1898, no. 21, p. 5.

[17] The Parliamentary Debates, 1907, vol. CLXIX, p. 408.

[18] C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, 1914, London, p. 16

[19] Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913, p. 172

[20] “Smallpox in the United States: Its decline and geographic distribution,” Public Health Reports, vol. 55, no. 50, December 13, 1940, pp. 2303-2312

This is important information!

Born in ’69 I did not get the vax for the common childhood diseases. When I asked my mom she said I had been through all of them without any issues.

I only remember measles. Woke up with red spots all over my body that faded within an hour or so. That was it, did not feel sick or anything. But I do know one person who got very sick and who's parents operated a junkfood place. My mom cooked meat and veggies every day.