The Charts Don’t Lie

Infectious Diseases Were Already in Freefall Before Vaccines and Antibiotics

By the time laboratory medicine came effectively into the picture the job had been carried far toward completion by the humanitarians and social reformers of the nineteenth century... When the tide is receding from the beach it is easy to have the illusion that one can empty the ocean by removing the water with a pail.

— René Dubos, Mirage of Health

The decline of mortality in the nineteenth century was due primarily to a large extent to the improved standard of living, especially the better diet of the people, and to a lesser extent to specific public health or medical interventions.

— Thomas McKeown, The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage, or Nemesis? (1976)

We are meant to be a modern society that relies on evidence and data to inform our decisions. In principle, especially regarding public health, this reliance on transparent scientific evaluation should be a foundational principle. Yet, many health policies enacted by governments—particularly those involving vaccination—are imposed through mandates rather than open, critical scientific scrutiny.

Some of these mandates are enforced through laws requiring vaccination for school attendance, regardless of individual beliefs or personal medical considerations. In more extreme cases, such as in Connecticut, governments do not permit religious or philosophical exemptions if a child does not complete the full vaccination schedule. During the recent COVID-19 fiasco, many individuals were coerced into receiving a newly developed biological product—labeled a vaccine—through threats of job loss and other forms of institutional pressure. Such coercive tactics to compel vaccination are not new; governments have used them since the mid-19th century.

If we, as a society, fail to analyze data critically, we risk supporting interventions that may have played only a minor or negligible role in the historical decline of mortality. Even worse, we risk ignoring or overlooking the very factors—improved sanitation, nutrition, housing, and working conditions—that were actually responsible for saving lives. By failing to investigate and act on these true drivers of health improvement, we do a profound disservice to the people of the world: wasting resources, misleading the public, and neglecting real solutions that could enhance well-being and quality of life. Instead, we elevate interventions that may be unnecessary—or even harmful—simply because they are backed by policy rather than rigorous data.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis was one of the most devastating public health threats for centuries, responsible for immense suffering and death, particularly among the impoverished. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, it ravaged populations in both America and Europe, claiming millions of lives. The death rate during the 1860s to 1880s was from 300 to 375 per 100,000. The standard narrative attributes its decline to the advent of antibiotics and vaccination—but the data tells a different story.

Historical records from Massachusetts show that tuberculosis was a leading cause of death throughout the 1800s. Yet by the time chemotherapeutic treatments like streptomycin (introduced in 1947) and the BCG vaccine arrived, the death toll had already plummeted, with the disease having been steadily retreating for decades.

As noted by medical historian Thomas McKeown, an extraordinary 96.8% reduction in tuberculosis mortality had already occurred before these medical interventions were introduced. While he acknowledged a further decline afterward, the data shows that the impact of antibiotics and vaccination was relatively minor, if any, in the broader historical context:

“Chemotherapy [Streptomycin, 1947; BCG Vaccination, 1954] reduced the number of deaths [from tuberculosis] in the period since it was introduced (1948-1971) by 51 per cent; for the total period since cause of death was first recorded (1848–71) the reduction was 3.2 per cent.”[1]

Similar trends are evident in the data from England and Wales, where respiratory tuberculosis mortality had already undergone a dramatic decline well before modern medical tools were deployed. These patterns strongly suggest that the primary drivers of tuberculosis control were improvements in living conditions—such as sanitation, nutrition, housing, and working environments—not vaccines or antibiotics.

Edward H. Kass notes in a 1971 article in The Journal of Infectious Diseases that tuberculosis mortality has declined steadily and almost linearly since the mid-19th century, largely unaffected by medical interventions such as vaccination, testing, or antibiotics. The decline persisted despite wars and hardship, with the poor suffering the most; however, no significant shift occurred due to scientific discoveries or public health campaigns.

“The data on deaths from tuberculosis show that the mortality rate from this disease has been declining steadily since the middle of the 19th century and has continued to decline in almost linear fashion during the past 100 years. There were increases in rates of tuberculosis during wars and under specified adverse local conditions. The poor and the crowded always came off worst of all in war and in peace, but the overall decline in deaths from tuberculosis was not altered measurably by the discovery of the tubercle bacillus, the advent of the tuberculin test, the appearance of BCG vaccination, the widespread use of mass screening, the intensive anti-tuberculosis campaigns, or the discovery of streptomycin.”[2]

Scarlet Fever

Before the modern era, scarlet fever ranked just behind tuberculosis as one of the deadliest infectious diseases in the industrialized world. While not as lethal as tuberculosis, its mortality rates often soared between 120 and 160 deaths per 100,000 during the 19th century, roughly 40% the fatality rate of tuberculosis. Despite its devastating toll, scarlet fever has largely vanished—not only from medical concern but from public memory as well.

Crucially, no widely adopted vaccine was ever developed for scarlet fever. Although antibiotics such as penicillin—first mass-produced in 1944— were eventually employed to treat the disease, the sharpest and most sustained decline in mortality occurred decades earlier, long before any medical intervention existed. As with tuberculosis, the disappearance of scarlet fever appears to have been driven primarily by broad, society-wide improvements in living conditions—especially enhanced hygiene, sanitation, nutrition, and housing—rather than by pharmaceutical or vaccine-based interventions.

Similar patterns are evident in data from England and Wales, among children under 15 years of age—the demographic most vulnerable to the disease. In this group, the mortality rate was significantly higher than that of the general population, reaching 150 to 240 deaths per 100,000 during the 19th century. Once again, this dramatic decline occurred without the help of any vaccine, reinforcing the argument that non-medical societal progress—rather than pharmaceutical intervention—was the primary driver of the mortality reduction.

Measles

Measles is a disease familiar to nearly everyone, often featured in news reports with urgency whenever a case emerges—frequently accompanied by a wave of public concern or even panic. Historically, measles was indeed a serious illness, with mortality rates ranging from 40 to 70 deaths per 100,000 during the 19th century—roughly one-half to one-third the fatality rate of scarlet fever.

Because a vaccine for measles now exists, it is commonly assumed that vaccination was the key factor behind the disease’s dramatic decline. However, data from England and Wales clearly show that the measles death rate had already fallen by nearly 100% before the introduction of the national measles vaccination program in 1968.

As with tuberculosis and scarlet fever, the overwhelming decline in measles mortality was largely the result of sweeping societal advancements—particularly improved sanitation, better nutrition, enhanced housing, and overall higher standards of living—long before the arrival of any pharmaceutical intervention. The data strongly suggest that it was these public health foundations—not vaccines—that were primarily responsible for taming measles as a deadly threat.

Similar patterns appear in data from England and Wales among children under 15—the age group most vulnerable to measles. In this population, mortality rates rose as high as 100 to 130 deaths per 100,000 during the 19th century, significantly exceeding the average for the general population. Yet, this steep and sustained decline in measles mortality occurred well before the introduction of any vaccine.

Once again, the data reinforces the broader conclusion: it was not pharmaceutical intervention, but instead sweeping improvements in public health infrastructure—such as sanitation, housing, nutrition, and hygiene—that drove the decline in deaths. By the time the measles vaccine was introduced, the disease had already ceased to pose a significant danger.

Whooping Cough

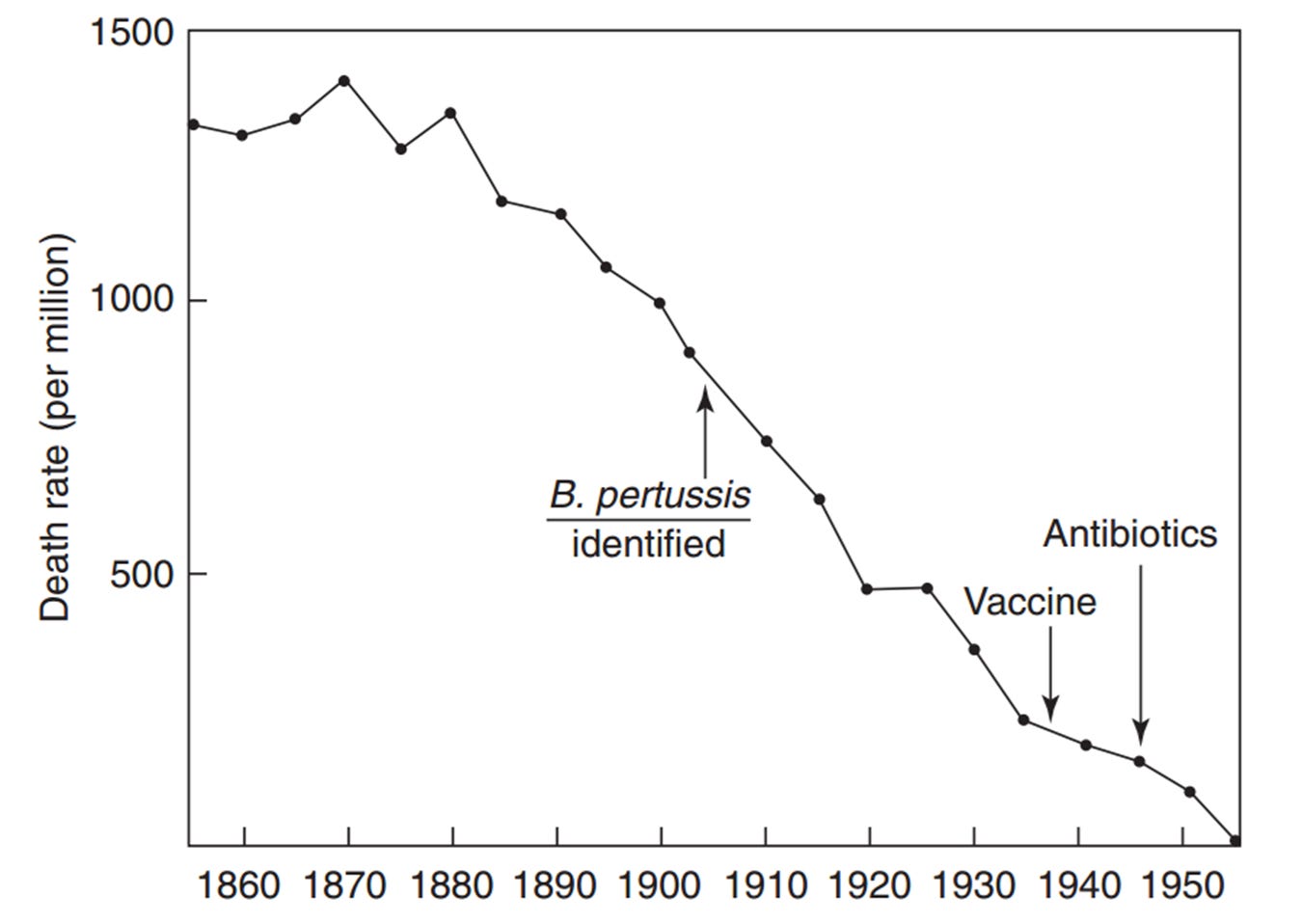

Much like measles, whooping cough (pertussis) was once a serious and often deadly childhood illness, with mortality rates in the 19th century routinely ranging between 40 and 70 deaths per 100,000. Today, because a vaccine for whooping cough—DTP/DTaP—is widely available, many assume that this medical advance was chiefly responsible for the disease’s sharp decline.

However, historical data from England and Wales tell a different story. The vast majority of the drop in whooping cough mortality occurred well before the launch of widespread vaccination programs. In fact, the death rate had already plummeted by nearly 100% by the time the national measles vaccination campaign was introduced in 1957.

As with other infectious diseases of the era, the real turning point came from non-medical advances: cleaner water, improved sewage systems, better diets, more stable housing, and broader societal efforts to raise living standards. These foundational public health measures appear to have played the dominant role in curbing whooping cough mortality. The evidence is clear: it was not vaccines, but a healthier society, that turned this once-deadly disease into a manageable one.

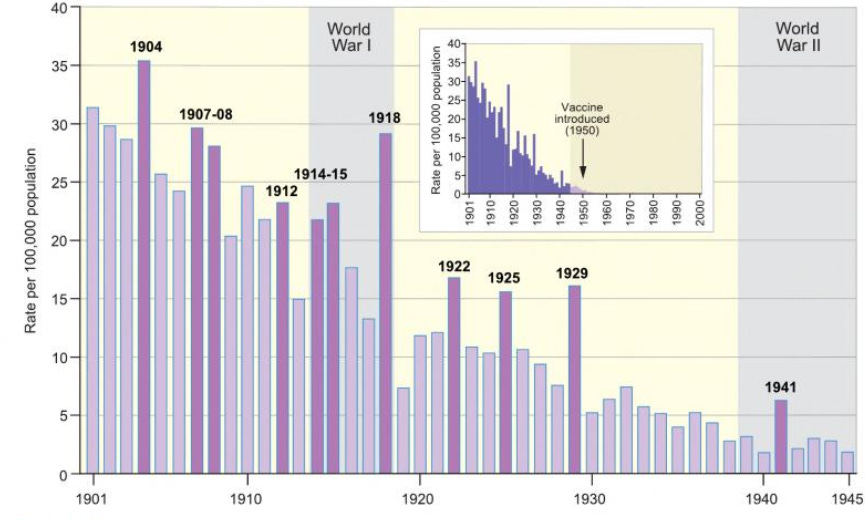

The data is also presented in a slightly different chart format in the 2012 book Atlas of Epidemic Britain: A Twentieth-Century Picture. This includes a bar chart illustrating annual death rates from whooping cough per 100,000 population in England and Wales between 1901 and 1945.[3] Years with unusually high mortality compared to the overall trend are highlighted with dark purple bars. An inset graph places this period in a broader, century-long perspective from 1901 to 2000. During the twentieth century, a total of 233,698 deaths from whooping cough were recorded in England and Wales, with over 97% occurring within the 1901 to 1945 timeframe.

A similar trend is evident in historical data from England and Wales for children under 15—the demographic most vulnerable to whooping cough. In this age group, mortality rates during the 19th century reached alarming levels, rising to 100 to 140 deaths per 100,000, far exceeding the rate seen in the general population. And yet, the dramatic and consistent decline in whooping cough-related deaths began decades before any vaccine was introduced.

Once more, the pattern is unmistakable: the steep reduction in mortality was not driven by pharmaceutical interventions, but by broad-based public health progress. Enhanced sanitation systems, better housing, improved nutrition, and advances in personal hygiene played the most pivotal roles in reducing deaths from whooping cough. Likewise, the whooping cough vaccine emerged only after that illness, too, had already ceased to be a major killer—further reinforcing the conclusion that societal conditions, not medical products, were the primary force behind these public health victories.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Roots of Public Health Progress

The sweeping decline in infectious disease mortality over the past two centuries is frequently hailed as one of the greatest triumphs of modern medicine. Yet this popular narrative often overlooks the broader context—and the deeper forces—that truly reshaped public health. While medical interventions such as vaccines and antibiotics are credited with saving millions of lives, the timeline tells a more complex story, one in which societal and environmental changes played the leading role.

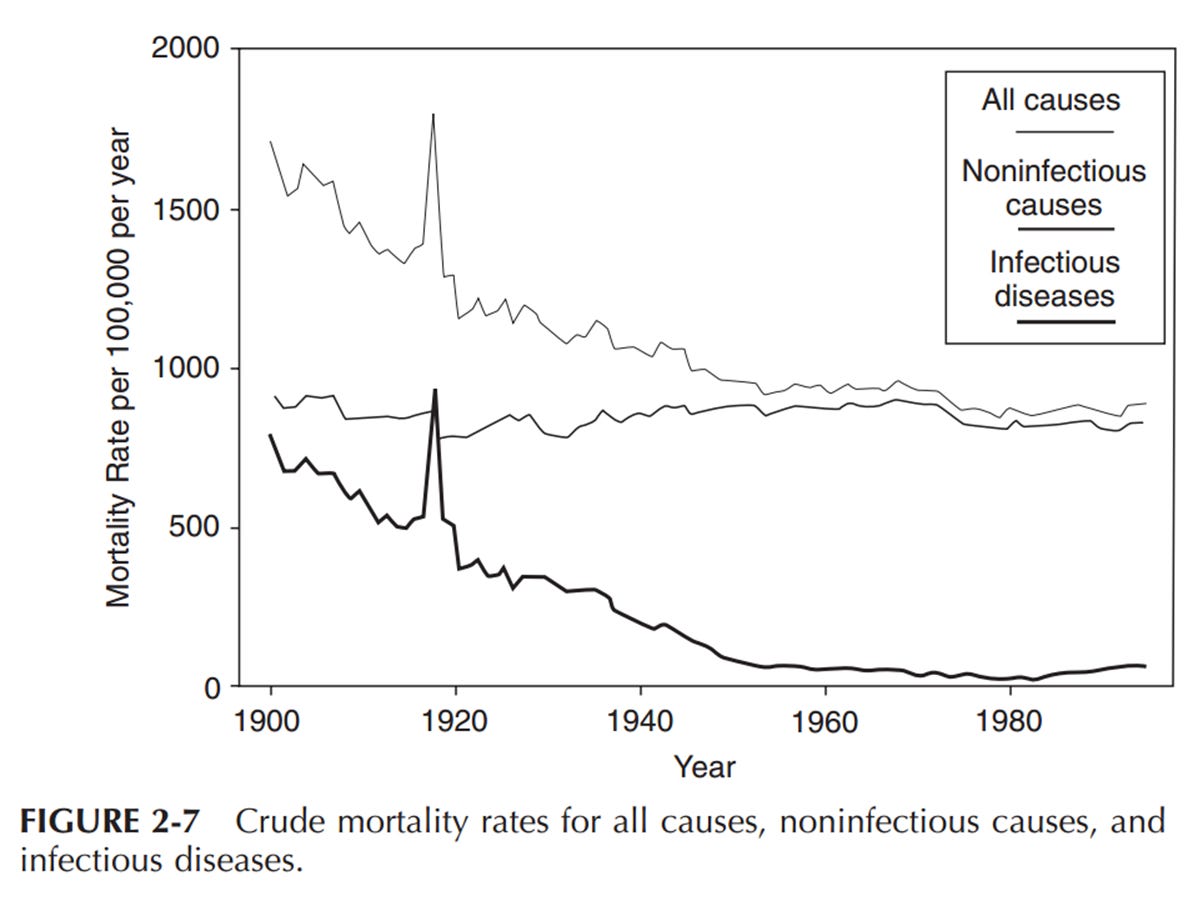

As Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice acknowledges:

“Although the crude mortality rate for infectious diseases was dramatically reduced during the first eight decades of the 1900s, the mortality from all noninfectious diseases has not shown a similar change (Figure 2-7). In fact, most of the decline in mortality during the 1900s can be attributed to the dramatic reduction in infectious disease mortality. In the last two decades of the 1900s, the mortality from coronary heart disease has declined substantially; however, this has been offset by increasing mortality for lung cancer and other diseases. Clearly, the decline in mortality from infectious diseases during the 1900s stands as a tribute to the advances in public health and safer lifestyles, compared with that in previous centuries.”[4]

Rather than pharmaceutical breakthroughs, it was socioeconomic progress—better housing, cleaner water, improved nutrition, safer working conditions, and overall hygiene—that drove this transformation. As that same source observes:

“Similarly, death rates from scarlet fever, diphtheria, and whooping cough (pertussis) in children under age 15 in England and Wales began to decline well before these organisms were identified in the laboratory, and the availability of effective antibiotics had a small effect on the overall mortality decline.”[5]

And yet, despite the significance of these developments, the mechanisms remain poorly understood. The editors of Infectious Disease Epidemiology go further:

“…trends in mortality have been reported with respect to diphtheria, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, pertussis, measles, and many others… This decline in rates of certain disorders, correlated roughly with improving socioeconomic circumstances, is merely the most important happening in the history of the health of man, yet we have only the vaguest and most general notions about how it happened and by what mechanisms socioeconomic improvement and decreased rates of certain diseases run in parallel.”[6]

Physician W.J. McCormick, in a 1951 article, presented a compelling challenge to the conventional wisdom that medical advances were primarily responsible for the decline in infectious diseases. Drawing on a comprehensive review of the literature, he noted that the timing and scale of mortality reduction did not align with the introduction of medical interventions. McCormick’s insight underscores a central theme echoed across historical and epidemiological research: that the primary engine behind the disappearance of many deadly diseases was not medicine per se, but widespread improvements in living conditions and public health.

“The usual explanation offered for this changed trend in infectious diseases has been the forward march of medicine in prophylaxis and therapy but, from a study of the literature, it is evident that these changes in incidence and mortality have been neither synchronous with nor proportionate to such measures. The decline in tuberculosis, for instance, began long before any special control measures, such as mass x-ray and sanitarium treatment, were instituted, even long before the infectious nature of the disease was discovered. The decline in pneumonia also began long before the use of the antibiotic drugs. Likewise, the decline in diphtheria, whooping cough and typhoid fever began fully years prior to the inception of artificial immunization and followed an almost even grade before and after the adoption of these control measures. In the case of scarlet fever, mumps, measles and rheumatic fever there has been no specific innovation in control measures, yet these also have followed the same general pattern in incidence decline. Furthermore, puerperal and infant mortality (under one year) has also shown a steady decline in keeping with that of the infectious diseases, thus obviously indicating the influence of some over-all unrecognized prophylactic factor.”[7]

Even leading medical journals have recognized the limited role of vaccination in driving the historical decline of certain infectious diseases. In its 1977 review of whooping cough (pertussis), The Lancet—one of the most respected names in medical publishing—offered a striking assessment of the disconnect between vaccine introduction and mortality trends:

“There was a continuous decline, equal in each sex, from 1937 onward. Vaccination [for whooping cough], beginning on a small scale in some places around 1948 and on a national scale in 1957, did not affect the rate of decline if it be assumed that one attack usually confers immunity, as in most major communicable diseases of childhood... With this pattern well established before 1957, there is no evidence that vaccination played a major role in the decline in incidence and mortality in the trend of events.”[8]

This candid admission stands in sharp contrast to the dominant narrative that credits vaccination as the pivotal turning point in the control of childhood diseases. The data, as The Lancet acknowledged, tell a different story—one in which the most substantial decline in whooping cough mortality occurred well before the vaccine was rolled out on a national scale.

Rather than being the catalyst for improved outcomes, vaccination appears to have followed a trajectory of decline already firmly in place—driven largely by improved sanitation, nutrition, and living conditions. The statement by The Lancet underscores the importance of revisiting historical trends with a critical eye, and of questioning assumptions that have long gone unchallenged.

Taken together, these findings challenge the dominant narrative that credits vaccines and antibiotics with the lion’s share of public health successes. They urge us to look deeper, to recognize the broader context in which disease burdens were lifted—not primarily through laboratories and syringes, but through the work of reformers, engineers, educators, and an awakened public conscience.

As René Dubos eloquently observed:

“By the time laboratory medicine came effectively into the picture the job had been carried far toward completion by the humanitarians and social reformers of the nineteenth century... When the tide is receding from the beach it is easy to have the illusion that one can empty the ocean by removing the water with a pail.”[9]

The real lesson of history is not that science failed, but that we have profoundly misattributed the impact of specific medical interventions—especially vaccines and antibiotics. In our eagerness to celebrate technological breakthroughs, we have too often overlooked the quieter, more powerful forces that reshaped human health: cleaner water, adequate nutrition, safer housing, improved labor conditions, and equitable access to the essentials of life. These were not miracles of medicine but hard-won victories of public infrastructure, social reform, and collective action.

By placing all credit at the feet of pharmaceuticals, we risk ignoring the true foundations of health—and, worse, allowing those foundations to continue to erode. If we are to build a healthier future, we must look beyond the needle and the pill. We must reclaim and reinvest in the tools that truly transformed society: justice, dignity, clean environments, and the shared will to care for one another. Let us remember what really made the difference—and ensure those lessons are not lost to the myths of medical modernity.

[1] Thomas McKeown, The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage, or Nemesis? 1979, Princeton University Press, p. 93.

[2] Edward H. Kass, Infectious Diseases and Social Change, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, January 1971, vol. 123, no. 1, p. 111.

[3] Matthew Smallman-Raynor and Andrew Cliff, Atlas of Epidemic Britain: A Twentieth Century Picture, 2012, Oxford University Press, p. 52.

[4] Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice, edited by Kenrad E. Nelson and Carolyn Masters‑Williams, pp. 51-52.

[5] Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice, edited by Kenrad E. Nelson and Carolyn Masters‑Williams, p. 52.

[6] Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice, edited by Kenrad E. Nelson and Carolyn Masters‑Williams, p. 52.

[7] W. J. McCormick, MD, “Vitamin C in the Prophylaxis and the Therapy of Infectious Diseases,” Archives of Pediatrics, vol. 68, no. 1, January 1951.

[8] “Vaccination Against Whooping-Cough: Efficacy Versus Risks,” The Lancet, January 29, 1977, pp. 236, 237.

[9] René Dubos, Mirage of Health.

Two of our children were vaccinated for pertussis per the CDC schedule, and both caught pertussis as toddlers. It took 3 visits to the pediatrician to determine their illness - The pediatricians themselves didn’t know that the pertussis vaccine does not prevent illness/transmission. Subsequently, the county public health office called to ask if our children were vaccinated for pertussis. We told them yes so why did they catch it? The county rep went on to blame the “unvaccinated” for driving pertussis virus evolution/ new strains.

Despite this experience, it wasn’t until the advent of the covid pandemic that our eyes were opened to the true risk/reward profiles of vaccines, the corrupted studies and the irrational justifications. While we had declined the Vitamin K drops for our children at birth and delayed the Hep B shot, we regret not seeing the truth earlier. We would have certainly done things differently. While Covid has been a traumatic experience for all (including deaths of family members), the only silver lining is that it has awakened so many to the institutional corruption and the vital need to do one’s own research and question all proposed interventions.

Thank you for your thoughtful research and compelling charts that can help us awaken others. We are grateful for all of your efforts!

Thank you so much for this even greater clarity. I had wondered about tb as it was something that people remembered when I was a child and had obviously feared. I remember getting a tb test (which they called a BCG) and a tb shot at school in the fifties in England.

Interestingly, James Herriot, vet and author (All Creatures Great and Small) who was well known as a vet in North Yorkshire, spoke about the government rolling out the tb injections in cows and I remember drinking TT tested milk.

I noted recently on listening to these stories again, that they saw this as a good thing, not only from a payment point of view, but from a health point of view.