“Medicine is a great humbug. I know it is called a science. Science, indeed! It is nothing like science. Doctors are mere empirics, when they are not charlatans. We are as ignorant as men can be… I know nothing in the world about medicine, and I don’t know anybody that does know anything about it. I repeat it. Nobody knows anything about medicine. I repeat it to you, there is no such thing as medical science.”[1]

― Dr. Francois Magendie, 1856

“No sooner did Dr [Jenner] announce his discovery to the public, and its merits were examined, than every facility was given to its circulation. The rage was extreme, and fashionable, not only amongst the medical profession; but all classes of society...”[2]

― Thomas Brown, Surgeon, 1809

“I’m trying to free your mind, Neo. But I can only show you the door. You’re the one that has to walk through it.”

― The Matrix, 1999

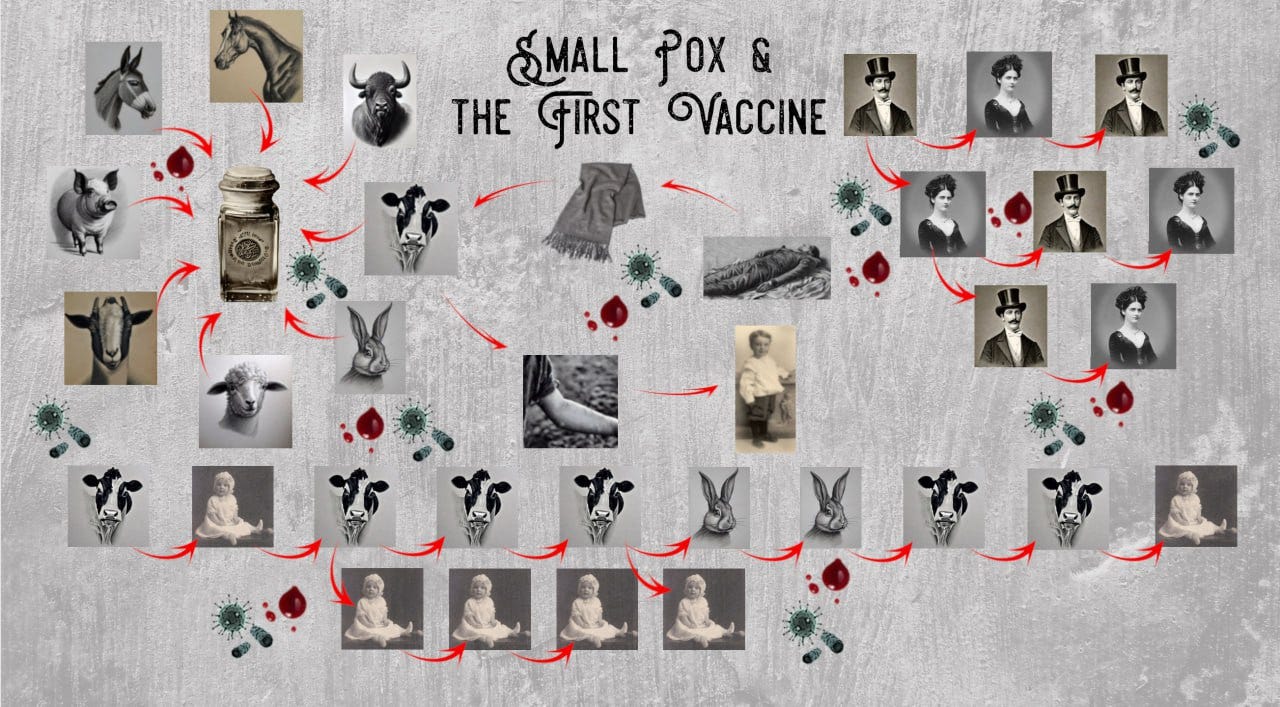

Vaccination. The history of smallpox and its supposed cure is a tale of bizarre theories, tragic failures, and relentless resistance. In the late 17th century, Thomas Sydenham, the Father of English medicine, called smallpox “the most slight and safe of all diseases” when properly managed. Yet, by 1721, variolation—deliberate infection with smallpox—was killing 2–3% of those inoculated, proving as dangerous as the disease itself. Edward Jenner’s cowpox experiments in 1796 sparked hope, but early vaccines were unreliable. In 1801, a Massachusetts vaccination campaign unleashed a smallpox outbreak, claiming 68 lives. By 1810, the Medical Observer documented 535 cases of smallpox after vaccination, including 97 fatalities. Compulsory vaccination laws in the 19th century failed to halt epidemics; in 1873, over 122,000 vaccinated individuals in England still contracted smallpox.

By the late 1800s, smallpox had mutated into a milder illness, often indistinguishable from chickenpox, even as vaccination rates declined. In 1897, a mild smallpox outbreak spread across the United States, yet mortality rates plummeted to unprecedented lows. By 1908, the fatality rate had dropped to 0.26%—a staggering 98.7% decrease from 1895. In England, vaccination rates plunged after the introduction of conscientious objection clauses in 1897, yet smallpox deaths continued to decline. By 1948, the Leicester experiment proved that smallpox could be controlled with isolation and sanitation alone—despite vaccination rates falling to just 18%. Dr. Thomas Mack later argued that smallpox faded due to economic development, not vaccines.

The story of vaccination is far from the clean-cut victory we’re told it is. It’s a chaotic, controversial saga—littered with dubious claims, deadly mistakes, and bitter disputes. The history of smallpox and vaccination is as unsettling as it is revealing. Dare to dig deeper? The truth might shake everything you thought you knew.

1681: Dr. William Cole writes in a letter to Thomas Sydenham, MD, “I heartily thank you for your method of Cure in the Small-pox, whereby that dreadful Disease (unless some malignity, of some unusual thing happen, may be easily cured) if Nurses, a sort of People very injurious to the Health of Man, did not obstruct, who by the hot Regimen and Medicines, confound all things, and kill so many before their Time.[3]

1688: Thomas Sydenham, MD, renowned as the Father of English medicine notes: “…from all the observations that I can possibly make, that if no mischief be done, either by physician or nurse, it [smallpox] is the most slight and safe of all other diseases.”[4]

1717: Lady Mary Wortley Montague writes in a letter to Miss Sarah Chriswell, “The smallpox, so fatal and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless by the invention of engrafting.”[5] This starts the practice called variolation, which entailed taking a small amount of material from a human smallpox lesion and scratching it into another person's skin.[6]

1721: “Inoculation became fashionable and was fervently supported by many leading physicians in Europe. But there was a good deal of opposition, which increased when it became clear that success did not always follow. ‘The ensuing and protecting attack of smallpox was by no means always a mild one; it has been reckoned that two or three persons died out of every hundred inoculated.”[7]

1722: Isaac Massey, apothecary at Christ’s Hospital, shared his thoughts on the need for this inoculation. “Inoculation is an art of giving smallpox to persons in health, who might otherwise have lived many years, and perhaps to a very old age without it, whereby some unhappily come to an untimely Death.”[8] Having attended to the patients at Christ’s Hospital, which typically housed around 600 children, he observed that over 20 years, only 5 or 6 deaths were attributed to smallpox. Furthermore, in the preceding 8 years, the count stood at a mere solitary fatality. With four decades of experience in the medical field, Isaac Massey, had never witnessed a trend quite like this, and he fervently wished that very few patients would consent to undergo inoculation or, as he renamed it, “incantation.”

1724: Mrs. Anne Rolt recounted the harrowing death of her 9-year-old daughter after succumbing to the advice of her acquaintances to have her child inoculated. The inoculator had assured Mrs. Rolt that her daughter would remain in good health and would “play about the room the whole time” after undergoing the inoculation of smallpox and going through the induced disease process. “In nine Weeks after the Inoculation, and after the most miserable suffering, that ever poor creature underwent, she died worn to nothing but skin and bone.”[9]

1725: Strange and bizarre medical notions were being practiced very much akin to witchcraft. “From another standard medical work, “Collectanea Medica,” London, 1725, page 26 we find the following remedies: For Quinsy: powder of burnt owl, two drachms; burnt swallows, two drachms; cat’s brains, two drachms; dried and powdered blood of white puppy dogs, two drachms. For Colic: wolf’s guts, dried and powdered, two drachms; old man’s urine, three drachms; sheep’s excrements, two drachms; a sovereign remedy.”[10]

1747: Standard and commonly accepted medical procedures of that time included bleeding patients to the point of fainting, withholding even a single drop of cold water, depriving patients of light and fresh air, and promoting catharsis, which involved inducing forceful and abundant bowel movements through the use of cathartics. In 1747, Charles Perry, MD, noted some of these medical notions that were in widespread use in the treatment of smallpox. “Bleeding (which is now very generally practised amongst us, where Small Pox is expected, and even when it has just made its Appearance) is the first Thing necessary to be done; and ought to precede every Thing else... I advise Bleeding copiously... And this I advise to every one indiscriminately, without Regard to Age, Sex, or Temperament… The next Thing I advise, is to give a Vomit... This Medicine is evidently calculated to cleanse and empty the whole alimentary Tube, for it will purge as well as vomit…”[11]

1748: There was public acceptance of inoculation.[12]

1754: The Royal College of Physicians of London strongly endorsed inoculation.[13]

1764: Daniel Sutton introduced a new method of inoculation that greatly reduced the symptoms of the procedure and made it highly popular among the public. As a result, Sutton and those who followed his method became very wealthy. The Suttonian method of inoculation was widely accepted and remained popular in England until it was eventually replaced by Jenner's cowpox, later known as vaccination.[14]

1764: An article presented statistical data showing that inoculation led to an increase in smallpox and smallpox deaths.[15]

1767: Dr. Langton believed that the new Suttonian inoculation was perpetuated by a charlatan and that its popularity, which quickly spread across society, starting with the lower classes, was simply “popular madness.” He stated that this form of inoculation was “contagious caustic water, instead of laudable pus.”[16]

1768: Thomas Dimsdale visited Russia to inoculate Catherine the Great, the Empress of Russia, and her son against smallpox. He was rewarded with a fee of £12,000, an annuity for life of £500, and the rank of Baron for his services.[17]

1783: George III’s son Octavius dies following smallpox inoculation.[18]

1787: Edward Jenner went with his nephew George Jenner to look at a horse with diseased heels. Edward Jenner proclaimed, “There,” said he, pointing to the horse’s heels, “is the source of smallpox.[19]

1789: Edward Jenner conducted his first experiment on his 18-month-old son, Edward. He inoculated the child with swine-pox. Between that year and 1792, he continued to inoculate his son with smallpox repeatedly. It is possible that these experiments contributed to his son’s poor health and eventual death from tuberculosis, then known as consumption, at the age of 21.[20]

1790: Robert Walker MD writes that from 1731-1742 to 1763-1772, there was almost a 50% increase in smallpox deaths despite inoculation being widely used. In the twelve years from 1731 to 1742 inclusive, the average proportion of deaths by small-pox, is 74 in 1000; in the succeeding ten years [1743-1752], it is 83; in the next ten [1753-1762], it is 96; and in the last ten [1763-1772], when the disease and the method of treating it are supposed to be better understood than ever, it is increased to 109. Doth not this intimate connection between the progress of inoculation and the destructive increase of the small-pox, lead to a suspicion, that the one is, in some degree at least, influenced by the other?[21]

1796: Despite the widespread use of inoculation, a record smallpox epidemic was responsible for over 18% (nearly 1 in 5) of deaths. [22]

1796: Edward Jenner conducted an experiment in which he took fluid from a cowpox sore on the hand of a woman named Sarah Nelms and used it to inoculate an 8-year-old boy named James Phipps.[23]

1797: Because the dairies no longer appeared to have cowpox, Edward Jenner attempted to create the disease on the heels of a horse, “I even procured a young horse, kept in constantly in the stable, and fed him with beans to make is heels swell; but to no purpose.”[24]

1798: Smallpox vaccination was introduced by Edward Jenner (1749-1823). He published a work titled ‘An inquiry into the causes and effects of variolae vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of Cow pox.’[25]

1799: Mr. Drake administered vaccinations to children using cowpox material obtained by Edward Jenner. However, when these children were later exposed to smallpox, they contracted the disease, indicating that the vaccination was ineffective. “The lad was inoculated with smallpox on the 20th December, being the eighth day from his vaccination, and the two children on the 21st, being again the eighth day. They all developed smallpox.”[26]

1801: England—The adoption of vaccination was swift, with at least 100,000 individuals receiving the smallpox vaccine.[27]

1801: Marblehead, Massachusetts—A physician procured vaccine material from a sailor who had recently arrived from London and proceeded to vaccinate individuals in the town. Regrettably, this resulted in an outbreak of smallpox, causing sickness in 1,000 individuals and claiming the lives of 68 people.[28]

1802: Edward Jenner presented a petition to the House of Commons, claiming to have discovered a method of inoculation using cowpox that was safe, protected individuals from smallpox for life, and would ultimately safely and easily “annihilate” smallpox. “That your petitioner, having discovered that a disease which occasionally exists in particular from among cattle, known by the name of cow-pox, admits of being inoculated on the human frame with the most perfect ease and safety, and is attended with the singular beneficial effect of rending through life the person so inoculated perfectly secure from the infection of small-pox... and from its nature must finally annihilate that dreadful disorder.”[29]

1804: Acting on Edward Jenner's recommendation, the King of Spain issued an order for all the children in the Foundling Hospital of Madrid to be vaccinated using goatpox.[30]

1805: John Birch, MRCS, London, notes experiments and reports show vaccination is a “fashionable rage” and “that what has been called the cow-pox is not a preservative against the natural small-pox.[31]

1805: Reports of smallpox and fatalities arising from those who have undergone cowpox or vaccination. “1. A Child was vaccinated by Mr. Robinson, surgeon and apothecary, at Rotherham, towards the end of the year 1799. A month later it was inoculated with small-pox matter without effect, and a few months subsequently took confluent small-pox and died. 2. A woman-servant to Mr. Gamble, of Bungay, in Suffolk, had cow-pox in the casual way from milking. Seven years afterwards she became nurse to Yarmouth Hospital, where she caught small-pox, and died. 3 and 4. Elizabeth and John Nicholson, three years of age, were vaccinated at Battersea in the summer of 1804. Both contracted small-pox in May, 1805 and died... 13. The child of Mr. R died of small-pox in October 1805. The patient had been vaccinated, and the parents were assured of its security. The vaccinator’s name was concealed. 14. The child of Mr. Hindsley at Mr. Adam’s office... died of small-pox a year after vaccination.”[32]

1810: The Medical Observer reports on cases of smallpox occurring after individuals have received cowpox or vaccination. “The Medical Observer for 1810 contains particulars of 535 cases of small-pox after vaccination, 97 fatal cases, 150 cases of vaccine injuries, with the addresses of ten medical men, including two professors of anatomy, who had suffered in their own families from vaccination.”[33]

1814: John Birch, MRCS, notes that he considered natural smallpox a mild disease and that it is “rendered malignant by mistakes in nursing, in diet, and in medicine, and by want of cleanliness…It would hardly he too bold to say, that the fatal treatment of this disease, for two centuries, by warming and confining the air of the Chamber, and by stimulating and heating cordials, was the cause of two-thirds of the mortality which ensued.”[34]

1817: Believing that horse grease was a source of “vaccine” Edward Jenner took that and supplied it to the national vaccine establishment where it would be widely be used. “Edward Jenner took matter from Jane King (equine direct) for the National Vaccine Establishment. The pustules beautifully correct. The matter from this source, was I believe, very extensively diffused. I received supplies of it, and it was likewise sent to Scotland. I may mention, at the same time, that some years before this period Mr. Melon of Lichfield has found the equine virus in his neighbourhood. He sent a portion to Dr. Jenner; and I believe it proved efficacious.”[35]

1817: An article in the London Medical Repository Monthly Journal and Review revealed that despite undergoing vaccination, many individuals were still contracting smallpox. “Variola [smallpox,] above all, continues and spreads a devastating contagion. However painful, yet it is a duty we owe to the public and the profession, to apprize them, that the number of all ranks suffering under Small Pox, who have previously undergone Vaccination by the most skillful practitioners, is at present alarmingly great.”[36]

1818: Musselburgh, Scotland—Thomas Brown, a highly experienced surgeon with over 30 years of practice, concluded that vaccination was ineffective after performing 1,200 vaccinations. Despite receiving the vaccination, many individuals were still contracting and dying from smallpox. As a result, he could no longer support vaccination to prevent smallpox. “Experience has also shewn [shown] that the natural small-pox have made their appearance, when the vaccine puncture had previously existed, surrounded with the areola of the most perfect appearance for more than two days, and not in the least modified, but in the highest degree confluent, and followed by death... The accounts from all quarters of the world, wherever vaccination has been introduced... the cases of failures are now increased to an alarming proportion…”[37]

1820: “Cases of small pox after cow pox, are become so common, as no longer to excite any interest. In one family we lately met with seven children laid up with small pox, all of whom had been vaccinated, some eight years, and others four years ago.”[38]

1822: Many cases of smallpox were reported among individuals who had previously contracted the disease or had undergone vaccination. “...during the years 1820, 1, and 2 [1820–1822] there was a great hubbub about the small-pox. It broke out with the great epidemic to the north... It pressed close to home to Dr. Jenner himself... It attacked many who had had small-pox before, and often severely; almost to death; and of those who had been vaccinated, it left some alone but fell up-on great numbers.”[39]

1829: Mr. Fosbroke observed in The Lancet that Edward Jenner had utilized lymph from a horse, not a cow, for several years. Additionally, other medical practitioners were found to have been using lymph from goats for inoculation.[40]

1829: William Cobbett, a farmer, journalist, and English pamphleteer, wrote about the failure of vaccination as a method to protect people from smallpox. “...in hundreds of instances, persons cow-poxed by JENNER HIMSELF [William Cobbett’s capital emphasis], have taken the real small-pox afterwards, and have either died from the disorder or narrowly escaped with their lives!” He calls vaccination “quackery.”[41]

1830: Barmen, Germany—Dr. Sonderland developed a technique of producing cowpox vaccine material by exposing cows to materials taken from patients who had died of smallpox, specifically by enclosing the heads of the cows in blankets that were used by patients who had succumbed to the disease. This method was intended to infect the cows with cowpox and generate a source of vaccine material.[42]

1834: An article by Dr. Fiard highlighted the confusion surrounding the true definition of a vaccine virus. The main theories surrounding the origin of the vaccine virus are: 1) it derived from a horse sickness known as ‘The Grease’; 2) it was a modified form of smallpox transmitted to cows; 3) it was a rare disorder specific to cows known as cowpox.[43]

1835: England and Wales—Act makes vaccination of infants compulsory.[44]

1836: Attleborough, Massachusetts—Smallpox is inoculated on a cow’s udder, and the product is used to vaccinate about 50 people. The result is an epidemic of smallpox, a panic, and the suspension of business.[45]

1836: Dr. Thiele successfully produced smallpox vaccine material by inoculating cows with variolous virus, which resulted in “the genuine vaccine disease.” Using this vaccine material, he vaccinated over 3,000 individuals through 75 transmissions.[46]

1840: The Vaccination Act banned variolation, a smallpox inoculation method that had been in use for nearly 120 years. It also established Britain's first free medical service by providing free infant vaccination.[47]

1840: Brighton, England—Mr. Badcock succeeded in small-poxing a cow and derived a stock of “genuine vaccine lymph.” He repeated the experiment about 600 times, succeeding in 37 cases. The virus obtained from these experiments has been distributed to many practitioners, resulting in tens of thousands of vaccinations being administered using this vaccine.[48]

1844: During a smallpox outbreak, approximately one-third of those vaccinated developed a mild form of the disease. However, a significant number of those vaccinated, around 8%, still died, and nearly two-thirds of cases among the vaccinated were severe.[49]

1850: A letter to the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle stated, “there were more admissions to the London Small-Pox Hospital in 1844 than in the celebrated small-pox epidemic of 1781 before vaccination was introduced.”[50]

1853: England—Smallpox vaccination was made compulsory for all newborn children.[51]

1854: “...a boy from Somers-town, aged 5 years, ‘small-pox confluent, unmodified (9 days).’ He had been vaccinated at the age of 4 months; one cicatrix... the wife of a labourer, from Lambeth, aged 22 years, ‘small-pox confluent, unmodified (8 days).’ Vaccinated in infancy in Suffolk; two good cicatrices... the son of a mariner, aged 10 weeks, and the son of a sugar baker, aged 13 weeks, died of ‘general erysipelas after vaccination, effusion of the brain.’”[52]

1855: Massachusetts—The government implements a comprehensive and strict set of vaccination laws. “...in 1855 Massachusetts took the most advanced stand ever taken by any of the states and enacted a law which required parents or guardians to cause the vaccination of all children before they were two years old, and forbade the admission of all children to the public schools of any child who had not been duly vaccinated.”[53]

1856: Dr. Francois Magendie writes “Medicine is a great humbug. I know it is called a science. Science, indeed! It is nothing like science. Doctors are mere empirics, when they are not charlatans. We are as ignorant as men can be… I know nothing in the world about medicine, and I don’t know anybody that does know anything about it. I repeat it. Nobody knows anything about medicine. I repeat it to you, there is no such thing as medical science.”[54]

1857: England—A smallpox epidemic claims more than 14,000 lives.[55]

1867: England—The Vaccination Act was passed, increasing the penalties for failure to vaccinate infants. Parents who failed to comply with the law faced fines or even imprisonment.[56]

1869: England—Henry Pitman’s Anti-Vaccinator is published.[57]

1870: United States, Boston, Massachusetts—Use of calf lymph for smallpox vaccination begins.[58]

1871: England—By this point, legislation had made vaccination mandatory, and Boards of Guardians were responsible for enforcing it, imposing repeated fines for non-compliance. In cases of failure to comply, parents faced the possibility of having their assets seized and being imprisoned.[59]

1873: England—Over 122,000 individuals who had been vaccinated contracted smallpox.[60]

1873: London—“The London Lancet of July 15, 1871, said: Of nine thousand three hundred and ninety-two [9,392] small-pox patients in London hospitals, six thousand eight hundred and fifty-four [6,854] [73%] had been vaccinated. Seventeen and one-half per cent [17.5%] of those attacked died.[61]

1873: Europe—“particularly in France and Germany, the visitation [of smallpox] was even more severe. Bavaria, for example, with a population vaccinated more than any other country in Northern Europe, except Sweden, which experienced the greatest that had ever been known. What was even more significant, many vaccinated persons in almost every place were attacked by small-pox before any unvaccinated persons took the disease.”[62]

1873: Boston—“The latest epidemic that of 1872-1873, having proved fatal to 1040 persons, was the most severe that has been experienced in Boston since the introduction of vaccination.”[63]

1874: England—The National Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League was established, which sparked acts of civil disobedience and led to the imprisonment of some individuals.[64]

1876: “...deaths from vaccination and re-vaccination are hushed up... Mr. Henry May, writing to the Birmingham Medical Review, January, 1874, on ‘Certificates of Death,’ says ‘As instances of cases which may tell against the medical man himself, I will mention erysipelas from vaccination and puerperal fever. A death from the first cause occurred not long ago in my practice, and although I had not vaccinated the child, yet in my desire to preserve vaccination from reproach I omitted all mention of it from my certificate of death.’”[65]

1877: Dr. Roth prescribed two tablespoons of vinegar, taken after breakfast and in the evening, for 14 days, as a treatment for those who were ill or had been exposed to smallpox. “Few persons thus treated took the disease at all. None who adopted the prophylactic treatment died, while among those under ordinary treatment, the mortality was as usual.”[66]

1878: English Parliamentary Returns No. 488, session of 1878: “Twenty-five thousand children are slaughtered annually by disease inoculated into the system by vaccination, and a far greater number are injured and maimed for life by the unholy rite.”[67]

1880: England—From 1870 to 1880 approximately 500 deaths were attributed to vaccination, with many succumbing to Erysipelas, a painful and fatal condition.[68]

1881: Leicester, England—Prosecutions for violating compulsory vaccination laws resulted in over 6,000 prosecutions, 64 resulted in imprisonment, and 193 distraints [seizure of property to obtain money owed] upon goods.[69]

1882: G. H. Merkel, MD stated, “The surgeon sat on a box in the storeroom, lancet in hand, and around him were huddled as many as could be crowded into the confined space, old and young, children screaming, women crying; each with an arm bare and a woe-begone face, and all lamenting the day they turned their steps toward ‘the land of the free.’ The lymph used was of unknown origin, kept in capillary glass tubes, from whence it was blown into a cup into which the lancet was dipped. No pretence of cleaning the lancet was made; it drew blood in very many instances...”[70]

1884: At Highgate Hospital, there were 474 cases of smallpox, 447 of which had been vaccinated. Out of these vaccinated individuals, 43 [9.6%] died.[71]

1885: Germany—From 1870 to 1885 official returns indicate that over 15 years, one million individuals who were vaccinated against smallpox died from the disease.[72]

1885: Ivory points covered with “vaccine” material were used to give smallpox vaccinations by rubbing, scratching, or inserting the vaccine into cuts on the skin made by a lancet. It’s significant to highlight that Dr. Allnatt from Cheltenham, England, believed these ivory points could lead to death if inserted into the bodies of children with fragile constitutions. “Some of the vaccinators use real instruments of torture. Ivory points are driven into the flesh, and wounds ensue which become erysipelatous, and in the delicate constitutions of weakly children fatal.”[73]

1885: Leicester, England—Approximately 3,000 individuals faced legal action for failing to receive vaccinations. A significant rally against mandatory vaccination was held and was attended by a crowd of over 20,000. Event organizers stated that the number of participants was between 80,000 and 100,000.[74]

1886: In his book, The Value of Vaccination: A Non-partisan Review of Its History and Results, George William Winterburn, Ph.D., MD, pointed out that the practice of vaccination relied on a shaky foundation in terms of the methods used to create vaccines. “Millions of vaccinations are made every year, and nobody knows what they are made with. The whole process is a haphazard game with chance.”[75]

1888: Dr. Charles Creighton publishes an article opposing vaccination in the Encyclopedia Britannica.[76]

1888: Dr. T. V. Gifford states, “It is a convenient habit of vaccinators to speak of vaccinations as uniform, as if the virus of the rite were as definite as a drop of water, a pinch of salt, or a grain of gold. Nothing could be further from the truth. The virus called vaccine is not one but various, not uniform but multiform, not certain but uncertain with an uncertainty which in transit from body to body, ad infinitum, can be predicted nor ascertained... The matter of his lancet he cannot define and its effects he cannot foresee... To these Jennerian stocks have been added Smallpox Cowpox obtained by inoculating cows with the virus or pus of human smallpox. Thus we have virus derived from horse grease cowpox, from natural or spontaneous cowpox, from horsepox, and from smallpox cowpox, plus the constitutional taints of the generations of vaccinifers through which these diverse poxes have been passed; and which is which, and how modified for better or for worse in the course of travel none can tell.”[77]

1889: Italy—Despite a vaccination coverage rate of 98.5%, there were 16,249 deaths from smallpox in 1887, 18,110 in 1888, and 13,413 in 1889.[78]

1889: Dr. Charles Creighton, MD, professor University of Cambridge stated, “It is difficult to conceive what will be the excuse for a century of cow-poxing; but it cannot be doubted that the practice will appear in as absurd a light to the common sense of the twentieth century as blood-letting now does to us. Vaccination differs, however, from all previous errors of the faculty, in being maintained as the law of the land on the warrant of medical authority. That is the reason why the blow to professional credit can hardly help being severe, and why the efforts to ward it off have been, and will continue to be so ingenious.”[79]

1890: Leicester, England—The vaccination rate among new births dropped to just 5%.[80]

1892: Japan—“...the official records show that during the seven years mentioned [1885–1892], they had 156,175 cases of small-pox and 39,979 deaths. By a compulsory law, every infant in Japan had to be vaccinated within the first year of its birth and in case it did not take the first time, three additional vaccinations had to follow within the year, and every year to seven years after.”[81]

1893: The Leicester Method, a method of smallpox control, demonstrated its effectiveness during an outbreak. Despite the majority of the population being unvaccinated, the town had a case-fatality rate of 5.8%, significantly lower than in neighboring towns with higher vaccination rates.[82]

1894: The process of retro-vaccination, in which the virus is passed from children to calves and back to children repeatedly, was believed to be a scientifically sound method for maintaining the effectiveness of the vaccine material.[83]

1897: England—Vaccination Act outlawed arm-to-arm vaccination, which had been used for 100 years. It also includes the exemption clause, thus introducing the concept of ‘conscientious objection’ into English law.[84] Parents can apply in police courts for certificates exempting their offspring from vaccination. Still, the stipulation and stumbling block were that the applications needed to “satisfy” the justices of the bona fides of their conscientious objection. However, many of these magistrates refused to be satisfied. “But the fact that three-quarters of a million of these official exemption certificates were actually obtained evidences the strong volume of public opinion adverse to the cowpox ring.”[85]

1897: After the summer of 1897, the severe type of smallpox with its high death rate, with rare exceptions, had entirely disappeared from the United States. ‘During 1896, a very mild kind of smallpox began to prevail in the South and later gradually spread over the country. The mortality was very low, and it [smallpox] was usually at first mistaken for chicken pox or some new disease called “Cuban itch,” “elephant itch,” “Spanish measles,” “Japanese measles,” “bumps,” “impetigo,” “Porto Rico scratches,” “Manila scab,” “Porto Rico itch,” “army itch,” “African itch,” “cedar itch,” “Manila itch,” “Bean itch,” “Dhobie itch,” “Filipino itch,” “nigger itch,” “Kangaroo itch,” “Hungarian itch,” “Italian itch,” “bold hives,” “eruptive grip,” “beanpox,” “waterpox,” or “swinepox.”’[86]

1897: Japan—“Another act passed in 1896 made repetition of vaccination every five years compulsory on every subject regardless of station; yet in the very next year, 1897, they had 41,946 cases of smallpox and 12,276 deaths—a mortality rate of 32 per cent, nearly twice that from smallpox previous to the vaccination period.”[87]

1899: Dr. Howe demonstrated vinegar’s ability to protect a person from acquiring smallpox. Those who used the vinegar protocol could take care of others with smallpox without fear of contracting the disease. The author notes that, despite several hundred exposures, vinegar was protective against smallpox and was considered an “established fact.”[88]

1901: Passaic, New Jersey—Approximately 350 women employed at the American Tobacco Company were involuntarily locked in the building and forced to receive vaccinations administered by health officers and police.[89]

1904: England—From 1881 to 1904 over 24 years, 1,041 deaths were reported by reputable physicians in England as being directly caused by cowpox or related effects of vaccination, according to their own certificates.[90]

1908: United States—According to the Surgeon General of Public Health report, between December 28, 1907, and February 21, 1908, 2,851 cases of smallpox in the United States, with only 9 deaths. A case/fatality rate of 0.32%. “It seems, therefore, that in spite of pest houses, maltreatment, unnecessary fear, and compulsory vaccination, smallpox is not a very fatal disease. And yet there is more fuss made about smallpox than all the other diseases put together.”[91]

1908: United States—Smallpox had become a mild illness, with a significant decrease in its fatality rate. The fatality rate of 20.84% in 1895 had dropped to an astonishing 0.26% [98.7% decrease].[92]

1910: North Carolina—3,875 cases of smallpox and 8 deaths, a fatality rate of 0.2%.[93]

1912: Passaic, New Jersey—Health Commissioner George Michels fights to keep his daughter from being vaccinated. He said, “I would move out of the State rather than be compelled to vaccinate my child. My father died of smallpox after being vaccinated and my sister was crippled through being vaccinated, and there are many cases on record in and out of the city of great harm and even death caused by vaccination.”[94]

1914: “For forty years, corresponding roughly with the advent of the ‘sanitary era,’ smallpox has gradually but steadily been leaving this country (England). For the past ten years, the disease has ceased to have any appreciable effect upon our mortality statistics. For most of that period, it has been entirely absent except for a few isolated outbreaks here and there. It is reasonable to believe that with the perfecting and more general adoption of modern methods of control and with improved sanitation (using the term in the widest sense), smallpox will be completely banished from this country as has been the case with plague, cholera, and typhus fever. Accompanying this decline in smallpox, there has been a notable diminution during the past decade in the amount of infantile vaccination. This falling off in vaccination is steadily increasing and is becoming very widespread.”[95]

1915: “The photographs are of Miss Fannie Lent, of Cincinnati, Ohio. She was vaccinated when a child, and thereafter became a mass of running sores. She visited Zion City a few years ago, and has since died. She suffered the tortures of hell, and was a sight that would melt a heart of stone. These pictures tell the story of what vaccination can do, and has done in thousands of cases. The time has come to down the dirty doctors, and drive vaccination back to hell where it came from.”[96]

1918: Camp Dodge, Iowa—Elmer N. Olson, a soldier in training from Goodrich, Minnesota, who refused to undergo vaccination, was put on trial by general court-martial and was sentenced to serve fifteen years in the disciplinary barracks at Fort Leavenworth.[97]

1920: Smallpox is now difficult to tell apart from chickenpox.[98]

1922: England—From 1857 to 1922, over 1,600 deaths were officially reported as a result of vaccination.[99]

1934: England—From 1914 to 1934, 107 children under five years of age died of smallpox, however 273 died of vaccination or 2½ times as many died from vaccination.[100]

1939: England—Only about 34% of children are vaccinated against smallpox.[101]

1939: United States—The 72,946 smallpox cases in 1902 fell to 9,877 in 1939 [86.5% decrease]. The 2,510 smallpox deaths in 1902 fell to 38 in 1939 [98.5% decrease]. The case/fatality rate of 4.24 in 1900 fell to 0.38 in 1939 [91% decrease].[102]

1948: England—Vaccination rate at 18%.[103]

1948: England—The Leicester experiment proved to be a success, as there were very few deaths from smallpox recorded since vaccination had been largely discontinued 62 years earlier. “Vaccination has been steadily declining [in England] ever since the ‘conscience clause’ was introduced until now nearly two-thirds of the children born are not vaccinated. Yet smallpox mortality has also declined until now quite negligible.”[104]

1948: United States—The last smallpox death occurred.[105]

1948: England—The idea of compulsory smallpox vaccination is finally abandoned with the introduction of the NHS.[106]

2002: Dr. Mack testified that his professional background includes extensive experience working with smallpox outbreaks in populations, likely more than virtually anybody ever has. He stated that smallpox disappeared due to advancements and improvements in society rather than universal vaccination. “If people are worried about endemic smallpox, it disappeared from this country not because of our mass herd immunity. It disappeared because of our economic development. And that’s why it disappeared from Europe and many other countries, and it will not be sustained here, even if there were several importations, I’m sure. It’s not from universal vaccination.”[107]

[1] “Paris Correspondence - Rue De La Chausee D’Astin, Paris, Feb. 24, 1856,” New York Medical Gazette and Journal of Health, vol. 7, no. 6, June 1856, p. 347.

[2] Thomas Brown, Surgeon, Musselburgh, An Inquiry into the Antivariolous Power of Vaccination; in which, from the state of the Phenomena and the occurrence of a great variety of Cases, the most Serious Doubts are suggested of the Efficacy of the Whole Practice, and its Powers at best proved to be only Temporary, Edinburgh, 1809, p. 3.

[3] John Pechey, MD, The Whole Works of that Excellent Practical Physician Dr. Thomas Sydenham, MD, 1696, London, p. 404.

R. G. Latham, MD, The Works of Thomas Sydenham, MD, vol. I, 1848, London, pp. lxxii–lxxiii.

[5] “Smallpox Superstitions,” The Columbus Medical Journal, December 1908, vol. XXXII, no. 12, pp. 686-687.

[6] William Douglass, MA, A Summary, Historical and Political, of the First Planting, Progressive Improvements and Present State of the British Settlements of North-America, London, 1760, London, R & J Dodsley, p. 407.

[7] Frederick F. Cartwright, Disease and History, 1972, Rupert Hart-Davis, London, p. 124.

[8] Isaac Massey, apothecary to Christ’s Hospital, A Short and Plain Account of Inoculation, 1722, London, pp. 20–21.

[9] Francis Howgrave, apothecary, Reasons Against the Inoculation of the Small-pox, 1724, Printed for John Clark at the Bible under the Royal-Exchange, pp. 26–28.

[10] Alexander Milton Ross MD, Fallacies and Delusions of the Medical Profession, 1888, Toronto.

[11] Charles Perry, MD, An Essay on the Smallpox, 1747, London. pp. 17–20.

[12] George Gregory MD, “Vaccination Tested by the Experience of Half a Century,” The Medical Times and Gazette, June 26, 1852, pp. 633–636.

[13] George Gregory MD, “Vaccination Tested by the Experience of Half a Century,” The Medical Times and Gazette, June 26, 1852, pp. 633–636.

[14] Giles Watts, M.D., A Vindication of the Method of Inoculating the Smallpox, 1767, London, p. v.

[15] “The Practice of Inoculation Truly Stated,” The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, vol. 34, 1764, p. 133.

[16] William Langton MD, An address to the public on the present method of inoculation: proving that the matter inoculated is not the small-pox. To which is added an inquiry into the nature of the confluent pox, and its cure, 1767, London, pp. 9–10.

[17] Henry Strickland Constable, Our Medicine Men: A Few Hints, 1876.

[18] Derrick Baxby, “The End of Smallpox,” History Today, March 1999, pp. 14–16.

[18] Walter R. Bett, The History and Conquest of Common Disease, 1954, University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 3–70.

[19] John Baron, MD, The Life of Edward Jenner, 1827.

[20] John Baron, MD, The Life of Edward Jenner, 1827.

[21] Robert Walker MD, An Inquiry into the Small-Pox, Medical and Political, 1790, London, p. 455.

[22] London Bills of Mortality.

[23] Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911, The Encyclopædia Britannica Company, New York, vol. XV, pp. 319–321.

[24] John Baron, MD, The Life of Edward Jenner, 1827.

[25] Velv W. Greene, PhD, MPH, “Personal Hygiene and Life Expectancy Improvements Since 1850: Historic and Epidemiologic Associations,” American Journal of Infection Control, August 2001, pp. 203–206.

[26] Charles Creighton MD, Jenner and Vaccination. A Strange Chapter of Medical History, 1889, Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

[27] Walter R. Bett, The History and Conquest of Common Disease, 1954, University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 3–70.

[28] Connecticut Gazette and the Commercial Intelligencer, January 1801.

[29] John Baron, MD, The Life of Edward Jenner, 1827.

[30] George William Winterburn, PhD, MD, The Value of Vaccination: A Non-partisan Review of Its History and Results, 1886.

[31] John Birch, MRCS, London, “Facts and Observations tending to disprove the efficacy of the practice of Vaccination, as a preventive of Small-Pox,” The Philadelphia Medical and Physical Journal, part I., vol. II, 1805, pp. 78–81.

[32] William Scott Tebb MD, A Century of Vaccination and What it Teaches, 1898, London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

[33] “Vaccination by Act of Parliament,” Westminster Review, vol. 131, 1889, p. 101.

[34] The Gentleman's Magazine, July 1814, p. 24.

[35] [35] John Baron, MD, FRS, Life of Edward Jenner, MD, vol. II, 1838, London.

[36] Observations on Prevailing Diseases,” The London Medical Repository Monthly Journal and Review, vol. VIII, July–December 1817, p. 95.

[37] Thomas Brown, Surgeon Musselburgh, “On the Present State of Vaccination,” The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. 15, 1819.

[38] The Monthly Gazette of Health, vol. V, no. 51, March 1, 1820, p. 439.

[39] “Observations by Mr. Fosbroke,” The Lancet, vol. II, 1829, pp. 583–584.

[40] “Observations by Mr. Fosbroke,” The Lancet, vol. II, 1829, pp. 583–584.

[41] William Cobbett, Advice to Young Men and (Incidentally) to Young Women, 1829, London, pp. 224–225.

[42] George William Winterburn, PhD, MD, The Value of Vaccination: A Non-partisan Review of Its History and Results, 1886.

[43] Dr. Fiard, “Experiments upon the Communication and Origin of Vaccine Virus,” London Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. 4, 1834, p. 796.

[44] Frederick F. Cartwright, Disease and History, 1972, Rupert-Hart-Davis, London.

[45] Ephraim Cutter MD, “Partial Report on the Production of Vaccine Virus in the United States,” Transactions of the American Medical Association, Volume XXIII, 1872.

[46] George William Winterburn, PhD, MD, The Value of Vaccination: A Non-partisan Review of Its History and Results, 1886.

[47] Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911, The Encyclopædia Britannica Company, New York, vol. XV, pp. 319–321.

[48] George William Winterburn, PhD, MD, The Value of Vaccination: A Non-partisan Review of Its History and Results, 1886.

[49] George Greogory, MD, “Brief Notices of the Variolous Epidemic of 1844,” Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society, January 28, 1845, p. 163.

[50] “Small Pox and Vaccination,” Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle, March 2, 1850.

[51] J. W. Hodge, MD, “State-Inflicted Disease in Our Public Schools,” Medical Century, vol. XVI, no. 10, October 1908, pp. 308–314.

[52] The Morning Chronicle, April 12, 1854.

[53] Susan Wade Peabody, “Historical Study of Legislation Regarding Public Health in the State of New York and Massachusetts,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, suppl. no. 4, February 1909, pp. 50–51.

[54] “Paris Correspondence - Rue De La Chausee D’Astin, Paris, Feb. 24, 1856,” New York Medical Gazette and Journal of Health, vol. 7, no. 6, June 1856, p. 347.

[55] J. W. Hodge, MD, “State-Inflicted Disease in Our Public Schools,” Medical Century, vol. XVI, no. 10, October 1908, pp. 308–314.

[56] Encyclopædia Britannica, 1890, The Henry G. Allen Company, New York, vol. XXIV, pp. 23–30.

[57] Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, 1997, Harper Collins Publishers, pp. 397–427.

[58] Walter R. Bett, The History and Conquest of Common Disease, 1954, University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 3–70.

[59] Stuart M. F. Fraser, “Leicester and Smallpox: The Leicester Method,” Medical History, 1980, vol. 24, pp. 315–332.

[60] The Parliamentary Debate, no.7, vol. XII, Fifth Volume of Session May 12, 1893, pp. 837–864.

[61] G. W. Harman, MD, “A Physician’s Argument Against the Efficacy of Virus Inoculation,” Medical Brief: A Monthly Journal of Scientific Medicine and Surgery, vol. 28, no. 1, 1900.

[62] Alexander Wilder, MD, “The Fallacy of Vaccination,” The Metaphysical Magazine, vol. III, no. 2, May 1898, p. 88.

[63] “Small-Pox and Revaccination,” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. CIV, no. 6, February 10, 1881, p. 137.

[64] Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, 1997, Harper Collins Publishers, pp. 397–427.

[65] The Ipswich Journal, November 7, 1876.

[66] “Acetic Acid in Scarlet Fever,” American Homoeopathist—A Monthly Journal of Medical Surgical and Sanitary Science, vol. 1, no. 1, July 1877, p. 73.

[67] Joe Shelby Riley, MD, MS, PhD, Conquering Units: Or The Mastery of Disease, 1921.

[68] The Parliamentary Debate, no.7, vol. XII, Fifth Volume of Session May 12, 1893, pp. 837–864.

[69] C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, pp. 1073–1075.

[70] Massachusetts Eclectic Medical Journal, November 1882.

[71] The Parliamentary Debate, no.7, vol. XII, Fifth Volume of Session May 12, 1893, pp. 837–864.

[72] G. W. Harman, MD, “A Physician’s Argument Against the Efficacy of Virus Inoculation,” Medical Brief: A Monthly Journal of Scientific Medicine and Surgery, vol. 28, no. 1, 1900.

[73] William White, The Story of a Great Delusion, 1885, London, E. W. Allen, p. xxxi.

[74] “Anti-Vaccination Demonstration at Leicester,” The Times, March 24, 1885.

[75] George William Winterburn, PhD, MD, The Value of Vaccination: A Non-partisan Review of Its History and Results, 1886.

[76] Derrick Baxby, “The End of Smallpox,” History Today, March 1999, pp. 14–16.

[77] Dr. T. V. Gifford, “What is Vaccination,” Journal of Hygeio-therapy, vol. II, no. 8, August 1888, p. 178.

[78] Charles Ruata, MD, “Vaccination in Italy,” The New York Medical Journal, July 22, 1899, pp. 188–189.

[79] Charles Creighton MD, Jenner and Vaccination. A Strange Chapter of Medical History, 1889, Swan Sonnenschein & Co., p. 354.

[80] J. W. Hodge, MD, “How Small-Pox Was Banished from Leicester,” Twentieth Century Magazine, vol. III, no. 16, January 1911.

[81] Simon L. Katzoff, MD, “The Compulsory Vaccination Crime,” Machinists’ Monthly Journal, vol. 32, no. 3, March 1920, p. 261.

[82] Stuart M. F. Fraser, “Leicester and Smallpox: The Leicester Method,” Medical History, 1980, vol. 24, pp. 315–332.

[83] “Massachusetts Medical Society, Suffolk District, Section for Clinical Medicine, Pathology and Hygiene – Regular meeting, Wednesday, February 21, 1894,” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, May 3, 1894, vol. CXXX, no. 18, pp. 447–450.

[84] C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, pp. 1073–1075.

[85] John H. Bonner, “The Death Knell of Vaccination,” The Columbus Medical Journal, October 1908, vol. XXXII, no. 10, pp. 535–536 John H. Bonner, “The Death Knell of Vaccination,” The Columbus Medical Journal, October 1908, vol. XXXII, no. 10, pp. 535–536.

[86] Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913.

[87] Simon L. Katzoff, MD, “The Compulsory Vaccination Crime,” Machinists’ Monthly Journal, vol. 32, no. 3, March 1920, p. 261.

[88] “Vinegar to Prevent Smallpox,” The Critique, January 15, 1899, p. 289.

[89] “Factory Girl’s Resistance, American Tobacco Company’s Employees’ Fight Against Compulsory Vaccination,” New York Times, April 12, 1901.

[90] J. W. Hodge, MD, “State-Inflicted Disease in Our Public Schools,” Medical Century, vol. XVI, no. 10, October 1908, pp. 308–314.

[91] “Smallpox in the United States,” The Columbus Medical Journal, April 1908, vol. XXXII, no. 4, p. 200.

[92] Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913.

[93] Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913.

[94] “Fights Vaccination Law, Passaic Health Commissioner Arrested for Refusing to Obey It,” New York Times, March 8, 1912.

[95] Dr. C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience, 1914, London.

[96] “Vaccination,” Leaves of Healing, January 2, 1915, vol. XXXV, No. 14, p. 313.

[97] “Refused Vaccination; Got 15 Years,” The New York Times, May 2, 1918.

[98] John Gerald Fitzgerald, Peter Gillespie, Harry Mill Lancaster, An introduction to the practice of preventive medicine, 1922, C.V. Mosby Company.

[99] J.T. Biggs, Leicester: Sanitation Versus Vaccination, 1912.

[100] J. H. Tilden MD, Miscellaneous Writings of J. H. Tilden, 1957.

[101] Derrick Baxby, “The End of Smallpox,” History Today, March 1999, pp. 14–16.

[102] “Smallpox in the United States: Its decline and geographic distribution,” Public Health Reports, vol. 55, no. 50, December 13, 1940, pp. 2303–2312

[103] Arthur Allen, Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver, 2007, p. 69

[104] C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, pp. 1073–1075.

[105] Gordon T. Stewart, “Whooping Cough in Relation to Other Childhood Infections in 1977–9 in the United Kingdom,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, vol. 35, 1981, p. 145

[106] C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, pp. 1073–1075.

[107] Transcript of the Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices held at the Atlanta Marriott Century Center, Atlanta, Georgia, on June 19 and 20, 2002.

Well-said: "the story", because smallpox is nothing more than a story. Viruses don't exist.

Oh, and Jenner just was a corrupt idiot.

https://odysee.com/@katie.su:7/thetruthaboutsmallpox:9

"Edward Jenner went with his nephew George Jenner to look at a horse with diseased heels. Edward Jenner proclaimed, “There,” said he, pointing to the horse’s heels, “is the source of smallpox."

Comedic gold..