Fishery management is an endless argument about how many fish there are in the sea until all doubt has been removed – but so have all the fish.

– John Gulland

There is a sufficiency in the world for man’s need but not for man’s greed.

– Mahatma Gandhi

We go about our days assuming the comforts we’ve built will always be there. Flip a switch, and the lights come on. Turn a knob, and clean water flows. Step outside, and food is waiting at the grocery store. Hop in a car or bus, and we’re off to wherever we need to go. With a phone or computer, information is at our fingertips. These conveniences have become so ingrained in our lives that it’s hard to imagine a time—just 100 years ago—when most of these things didn’t exist.

We trust others to fix what breaks and rely on countless systems to maintain our comfort and security. With our technology and ingenuity, we believe we can solve almost anything. Many look to governments and corporations to address the world’s most pressing issues, assuming they’re on top of things. But are they really? Are they so consumed by power, profits, and biases that they fail to see—or choose to ignore—the civilization-ending disasters looming on the horizon?

This series explores the critical issues we continue to overlook at our own peril.

In the first part of this series, we examined the fragility of the electrical grid—the lifeblood of modern societies—and how it could vanish in an instant.

https://romanbystrianyk.substack.com/p/we-are-not-prepared

Now, we turn our focus to the oceans, the blue heart of our planet, which are spiraling toward collapse under the weight of human activity. Our oceans, once thought inexhaustible, are buckling from overfishing, pollution, habitat destruction, and other factors. Over the past decades, we’ve stripped billions of tons of life from their depths, destabilizing ecosystems that have taken millennia to evolve. Entire species are disappearing, and the intricate web of marine biodiversity is unraveling. Without immediate and transformative action, we risk reaching a point where the oceans—critical to regulating Earth's climate and providing sustenance for billions—may no longer support the life they once teemed with.

In this exploration, we’ll uncover the drivers of this collapse and what can still be done to chart a course toward restoration and sustainability.

A brief history of overfishing

In the early sixteenth century, with the New World’s discovery, later called the Americas, numerous stories were reported to Europe of an endless abundance of Atlantic cod. This seemingly never-ending supply of cod helped fuel the new American colonies for generations and even gave Massachusetts’ famous cape its name, Cape Cod. At the turn of the sixteenth century, John Mason, an English fishing skipper working out of Newfoundland shore-station, noted,

Cods are so thick by the shore that we hardly have been able to row a boat through them... Three men going to Sea in a boat, with some on shore to dress them, in 30 days will commonly kill between 25 and thirty thousand...[i]

At that time, cod were reported to be up to six and seven feet in length (roughly 2 meters) and weigh as much as 200 pounds (90 kilograms), with their numbers dense enough to slow down boats.[ii] Hundreds of fishing vessels caught thousands of tons of cod off the New England coast. Boats took in a daily catch of 15,000 to 30,000 fish, and it seemed the fish were an “inexhaustible manna.”[iii] Nearly 200 years later, by the end of the seventeenth century, travelers such as Baron De Lahontan still commented on the seemingly endless quantities of cod off Newfoundland, Canada:

You can scarce imagine what quantities of Cod-Fish were catch’d [caught] there by our Seamen... yet the Hook was no sooner at the bottom, than the Fish was catch’d; so that had nothing to do but throw in, and take up without interruption.[iv]

Cod fishing off the coast of New England was a huge business. In 1763, the English at Newfoundland’s fisheries caught and cured 386,274 quintals (A quintal is an antiquated unit of weight equivalent to 100 kilograms or 220 pounds.) or about 42,500 tons of cod. That year, there were 106 fishing vessels with 265 ships transporting the salted cod to England and British Colonies. In 1783 the amount had increased to 591,276 quintals or over 65,000 tons of fish.[v] Presumably, due to centuries of intense fishing, by 1827, the largest cod had decreased in size to just over four feet long (1.3 meters), weighing in at 46 pounds (20 kilograms). As many as 1,500 English, American, and French fishing vessels extracted thousands of tons of cod off Newfoundland’s coast. A single fisherman was recorded to have caught about 12,000 cod annually, with the average fisherman catching about 7,000.[vi]

Still, the iconic cod proved not to be inexhaustible. After about 400 years of a strong fishing industry, the population of cod collapsed in 1992. Cod catches decreased from 500,000 tons in the Grand Banks in the 1960s to 50,000 tons.[vii] This led to a fishing moratorium that caused 40,000 people in Newfoundland to be thrown out of work.[viii] Inshore fishermen, like 76-year-old Wilson Hayward, believed the seeds of the collapse were sown after the Second World War. Hundreds of factory trawlers had arrived on the Grand Banks, which stretch out more than 320 kilometers (200 miles) off Newfoundland’s coast.

I remember going out on to the cape in the night, and all you could see were dragger (fishing trawler) lights as far as the eye could see, just like a city in the sea. We all knew it was wrong. They were taking the mother fish, which had been out there spawning over the years. They cleaned it all up; they dragged the ocean floor like the paved road.[ix]

Trawling is a fishing method involving dragging a net through the water behind a boat. Bottom trawling is when a fishing net is pulled across the seafloor.

Over the decades, fishing vessels advanced in size, power, and technology. In 1954, the first new factory freezer trawlers appeared. These ships could sweep up as many cod in two 30-minute trawls as could be caught during the entire summer season in the sixteenth century.[x] Factory trawlers, mostly from Europe but some from as far as East Asia, began large fishing operations with massive increases in catches by the 1960s and early 1970s. By the 1960s, pair trawlers – two vessels that tow a single net – had tripled in size and engine power in only a decade.[xi]

Atlantic cod, a relatively long-lived and slow-growing species, could not keep up with the increasing fishing rate. As the vast majority of spawning adults were packed into ships’ freezers, catches began to decline until they collapsed in the early 1990s.[xii] In 1492, the amount of fish off the coast of Nova Scotia was estimated to be 4,000,000 tons. By the early 2000s, that number had suffered a massive crash of nearly 99%, with only 50,000 tons remaining.[xiii]

The cod stocks off the coast of the United States still remain significantly below sustainable levels.[xiv] A study on Newfoundland's coast indicated the start of a recovery. The authors attributed the recovery to improved environmental conditions, better fish management, and the increased availability of the small fish they feed on, capelin, whose populations also fell drastically in the early 1990s. Even so, today’s cod, at an average length of about 2.2 feet (0.68 meters) and a weight of 8 pounds (3.6 kilograms),[xv] is at a meager less than 5% of the size of the legendary cod of the sixteenth century.

The collapse of the Atlanto-Scandian herring stands as one of the most dramatic and well-documented fish stock collapses in history. In just a few years during the late 1960s, annual catches plummeted from 600,000 tonnes to nearly zero. This crisis followed a prolonged decline in the herring population, exacerbated by relentless fishing pressure that drove the stock to the brink of disappearance.

The causes for this are also well known. In the 1960s a new technology, the power block, came on the scene and increased the fishing power of the boats many times over. Adverse environmental conditions, reflected in a falling ocean temperature, also helped. Lastly, the law of the sea at the time did not permit coastal states to exercise jurisdiction over fishing outside 12 nautical miles... The fishery was put under a moratorium, supported by Norwegian laws and regulations, and after nearly twenty years it recovered and has since supported catch volumes comparable to or even larger than before the collapse. [xvi]

Other fish stocks experienced similar overfishing and collapse. In the mid-seventeenth century, Nicolas Denys described his time along the Miramichi River, which flows through New Brunswick, Canada. He experienced sleepless nights because of the noise made by the massive amounts of salmon swimming in that river:

So large a quantity of salmon enters the river at night one is unable to sleep, so great is the noise they make in falling upon the water after having thrown or darted themselves into the air passing over the river flats. I found a little river which I named Riviere au Saulmon... I made a cast of the seine net [a fishing net that hangs vertically in the water with floats at the top and weights at the bottom edge] at its entrance where it took so great a quantity of salmon that then men could not haul it to land and... had it not broken the salmon would have carried it off. We had a boat full of them, the smallest three feet long.[xvii]

George Cartwright fished salmon for export in the late 1700s. He noted that the salmon were so thick that he could not have fired a shot into the river without hitting one. In 1799, he said, “In the Eagle River [Labrador, Canada], we are killing 750 salmon a day, and we would have killed more had we had more nets... the fish averaging from 15 to 32 pounds apiece.”[xviii]

Overfishing combined with lumber mills, damming of rivers, and pollution from tanneries and iron smelters caused the salmon populations to decline. John Rowan, an English visitor to Canada, noted as early as 1870 that the salmon fishing in Nova Scotia had already decreased due to these factors, and he predicted that eventually, the rivers would be “rendered barren.”[xix] Rowan’s prescient forecast came to pass in just a few years. By 1900, salmon were virtually extinct in Connecticut and Massachusetts and most New Hampshire and Maine rivers.[xx],[xxi] In the mid-1970s, North America's total population of Atlantic salmon was close to 1.8 million. By 2013, the population had fallen to one-third of that level.[xxii] As of 2017, the number of Atlantic salmon has continued to decline. A 2021 paper in Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture warned of the extinction of the wild North Atlantic salmon.

If the decline of the wild North Atlantic salmon population is not arrested, we suggest that more stocks will continue to collapse into a flatline state and others will disappear during the coming decade. Unless decisive action is taken wild Atlantic salmon could go the way of the anadromous houting, Coregonus oxyrinchus (Linneaus, 1758), which is virtually extinct except for a few isolated populations.[xxiii]

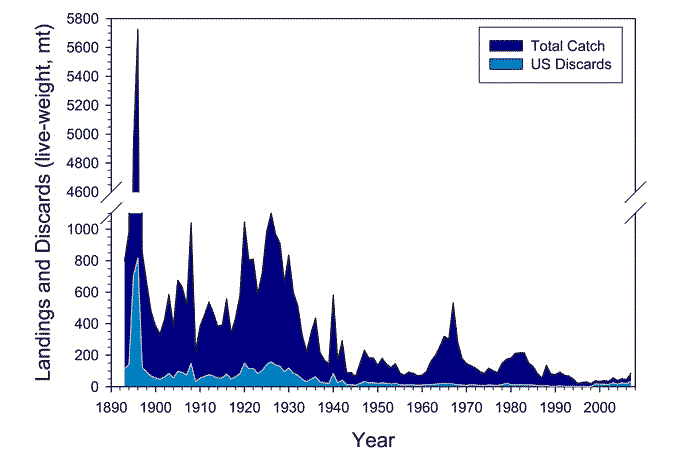

As fishing greatly expanded off the coast of New England in the early years of the New World, cod was the fish of choice. Although halibut was also incredibly abundant, it was discarded mainly because the meat was considered a poor choice for salting, which was the method of preserving fish at the time. Later, from the 1830s to the 1840s, many fishing vessels shifted to using ice to store fish, which was ideal for preserving halibut. This new preservation technology, along with a preferential cultural shift to fresh from salted fish, led to the halibut fishery’s height from the 1840s to the 1870s.

Atlantic halibut catches from the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank peaked in 1896 at 5,725 metric tons and decreased over the decades. In 1974, that number fell to 84 metric tons, peaking again in 1982 at 215 metric tons and then reducing to a low of 18 metric tons in 1998. The numbers remained well below 100 metric tons during the early 2000s, a tiny fraction of their once bountiful level during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Ravaging the oceans

Overall, the Northwest Atlantic has seen a significant decline in fish catch, down from about 4.2 million metric tons (4.6 million tons) in the early 1970s to 1.9 million metric tons (2.1 million tons) in 2013, more than a 50% drop. Strict regulations have been in place to allow for fish stock recovery, but some historically plentiful fish, such as cod, flounder, and redfish, are still showing little or no improvement.[xxiv] Atlantic cod catches remain extremely low since their collapse in the early 1990s.

The Bay of Bengal lies off the coast of India. The Bay’s fisheries have been severely depleted due to decades of overfishing. Many once-abundant species have all but vanished. Most unfavorably affected are the species at the top of the food chain. The man-eating sharks that were once feared by sailors are now rarely found in these waters. Other top predators like grouper, croaker, and rays have also been decimated. Fishing catches now are mainly made up of species like sardines, which are near the bottom of the marine food web.

Good intentions have played no small part in creating the current situation. In the 1960s, western aid agencies encouraged the growth of trawling in India, so that fishermen could profit from the demand for prawns in foreign markets. This led to a “pink gold rush,” in which prawns were trawled with fine mesh nets that were dragged along the sea floor. But along with hauls of “pink gold,” these nets also scooped up whole seafloor ecosystems as well as vulnerable species like turtles, dolphins, sea snakes, rays, and sharks. These were once called bycatch and were largely discarded. Today the collateral damage of the trawling industry is processed and sold to the fast-growing poultry and aquaculture industries of the region. In effect, the processes that sustain the Bay of Bengal’s fisheries are being destroyed in order to produce dirt-cheap chicken feed and fish feed.[xxv]

As many as 44,000 fishing boats and 147 trawlers skim the Bay of Bengal daily with sea-floor-scraping nets that rake up everything. Many fishing boats operate illegally, making the situation even worse. From 1985 to 2005, the amount of fish caught per net had dropped by about 80%, indicating the rapid decimation of fish stocks.[xxvi] This overexploitation may be disastrous for the region as the ever-shrinking Bay’s resources already endanger millions of livelihoods. A 2020 report on the state of fish in the Bay of Bengal indicates that most fish species are in decline, with some nearing extinction.[xxvii]

“Some seas in the world, like the Gulf of Thailand, have run out of fish,” one of the authors of the report, Sayedur Rahman Chowdhury, told BBC Bengali. Hundreds of large vessels are overfishing at an unsustainable rate, monitors suggest. Local fishermen say the government is turning a blind eye as the trawlers target key fish species they rely on.

In the 1980s and 1990s, fisheries expanded into new areas and began to target different species. Catch rates increased for some time but began declining in the late 1990s, forcing trawlers to move increasingly further from their home waters.

The Mergui archipelago on the Thai-Myanmar border is one of the more secluded parts of the Bay. In the late 19th century, an English fisheries officer described this area as being “literally alive with fish.” Today the archipelago’s sparsely populated islands remain pristinely beautiful while some of its underwater landscapes present scenes of utter devastation. Fish stocks have been decimated by methods that include cyanide poisoning.[xxviii]

Historically, the oceans were considered limitless and thought to be able to supply enough fish to feed an ever-increasing number of people. However, the demands of this ever-growing world population far outstrip the seas' sustainable yield. Historically, Fish has been a vital human food source, providing approximately 16% of the world’s animal protein. One billion people rely on fish as their primary source of protein.[xxix] As fisheries depleted and fish were more challenging to catch, many fishermen and governments responded with equipment and technology investments to fish longer and farther away from their home ports.

Consumer tastes in the First World have largely contributed to the problem. Increasing demand for top predators, such as swordfish or tuna, has put severe pressure on existing stocks... Long-line fishing for swordfish and other billfish

esmay significantly diminish the populations of many shark species, which are known to have slow reproductive rates and thereby slow recovery rates.

Having exhausted the ocean of fish close to Chinese shores, vast numbers of Chinese trawlers sail beyond their local waters to exploit other countries’ waters. These fishermen are subsidized by the Chinese government, which is not primarily concerned with the health of the world’s oceans and the other countries that depend on them. Increasingly, China’s expanding fleet of fishing vessels is heading to the waters of West Africa and off the coast of countries such as Senegal. Local fishermen cannot hope to compete with Chinese ships that are so massive that they drag up as many fish in one week as Senegalese boats catch in a year.[xxx]

In Senegal, an impoverished nation of 14 million, fishing stocks are plummeting. Local fishermen working out of hand-hewn canoes compete with megatrawlers whose mile-long nets sweep up virtually every living thing. Most of the fish they catch is sent abroad, with a lot ending up as fishmeal fodder for chickens and pigs in the United States and Europe.[xxxi]

Overfishing and habitat degradation have profoundly altered populations of marine animals, especially sharks and rays. Sharks are primarily caught to meet the demand for shark fin soup, a traditional and expensive Asian delicacy.[xxxii] After a shark is caught, its fins are cut off and kept, and then in a final cruel and heartless act, the maimed animal is often thrown back into the ocean, where it sinks and dies. Millions of finless shark carcasses litter the ocean bottom every year.[xxxiii]

Queensland’s shark control program, established in 1962 to “minimize the threat of shark attack on humans,” has caught and killed 50,000 sharks to date. As a result, shark populations have fallen off Australia’s east coast over the last 55 years. Hammerhead and great white sharks have plummeted by 92%, whaler sharks by 82%, and tiger sharks by 74%.[xxxiv]

An estimated 63 to 273 million sharks are killed yearly, 6 to 8% of all sharks in the ocean.[xxxv] This is equivalent to as many as 8 sharks being slaughtered per second. Because sharks are slow maturing and slow reproducing animals, their populations are being decimated. Elizabeth Wilson, Senior Director of Environmental Policy at The Pew Charitable Trusts, noted,

We are now the predators. Humans have mounted an unrelenting assault on sharks, and their numbers are crashing throughout the world’s oceans.[xxxvi]

A study published in the journal Nature in 2021 found that 18 shark and ray species populations have declined by 70% since 1970. The authors caution that many of these species might disappear entirely in a decade or two.[xxxvii]

Worldwide, fish extraction from the oceans peaked in 1996 at just over 86 million metric tons (94 million tons) and has generally declined since.[xxxviii] However, that number in 1996 may have actually been 130 million metric tons (143 million tons) if discarded and illegally caught fish are included. Thus, the already severe decline in fish stocks since the mid-1990s becomes three times larger than initially thought by including unaccounted for catches. Since 1996, fish catches have dropped, on average, a massive 1.2 million metric tons (1.3 million tons) every year.[xxxix] By 2010, fishers had a reduced yield of 109 million metric tons (120 million tons), a 16% decline since the peak in 1996 just 14 years earlier.[xl]

The fish killed but tossed back overboard, called bycatch or “trash fish,” and non-industrial levels of fishing account for one-fourth of fish catches. In the 1990s, between 20 and 27 million metric tons (22-30 million tons) of bycatch were discarded annually in the world’s commercial fisheries.[xli],[xlii] For shrimpers, 80% of everything caught is bycatch and thrown back for dead.[xliii] Today, nearly 10 million metric tons are still discarded, or about 10% of annual catches, despite declining fish stocks worldwide.[xliv] Fishers sometimes reject a portion of their catch because some caught fish are damaged and unmarketable, the fish are too small, the species is out of season, or the caught fish were not of interest. According to Dirk Zeller, a professor at the University of Western Australia,

Discards also happen because of a nasty practice known as high-grading where fishers continue fishing even after they’ve caught fish that they can sell. If they catch bigger fish, they throw away the smaller ones; they usually can’t keep both loads because they run out of freezer space or go over their quota.[xlv]

Still worse, a new phenomenon has emerged in Asia and elsewhere, where some trawlers no longer target particular fish. Instead, they scoop up any and all sea life that they find, turning this indiscriminate catch into fishmeal, fish oil, chicken feed, or surimi, the compressed white paste used to make fish cakes. Amanda Vincent, a professor at the University of British Columbia, has termed this extremely destructive practice “annihilation trawling.”[xlvi]

According to a United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) 2020 report on the state of the world’s fisheries, 34.2% of the world’s stocks are now overfished and unsustainable.[xlvii] An additional 59.6% of fish stocks are the maximum limit and have no room for further expansion. This leaves only 6.2% of the world’s fish stocks as so-called underfished. The over-exploitation of the planet’s fish has more than tripled since the 1970s. Lasse Gustavssin, the director of Oceana, a marine conservation body, stated,

We now have a fifth more of global fish stocks at worrying levels than we did in 2000. The global environmental impact of overfishing is incalculable, and the knock-on impact for coastal economies is simply too great for this to be swept under the rug anymore.[xlviii]

Still more concerning is a 2024 study that analyzed data from 230 fish stocks worldwide. It revealed that stock assessments frequently overestimated fish abundance while underestimating the time required for populations to recover and that the situation was worse that the FAO report.

The study also revealed that nearly a third of the stocks classified by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as “maximally sustainably fished” have actually crossed into the “overfished” category. Additionally, the number of collapsed stocks—those with less than 10% of their original biomass—is likely an astonishing 85% higher than previously estimated. [xlix]

Recent research by the North Atlantic Pelagic Advocacy Group (NAPA) says that if overfishing continues, the Atlanto-Scandian herring stock will repeat the collapse of the 1960s.

“The declining health of AS herring and the latest alarming forecast should send a sharp reminder to governments that stocks are at risk of collapse when they are overexploited year on year," said Erin Priddle, Regional Director for the Marine Stewardship Council in North Europe. The North-East Atlantic pelagic stocks represent one of the largest fish populations in Europe and are fished by some of the richest nations in the world. It would be an indictment of all governments involved if they continue to exceed the scientific advice by setting unilateral TACs [total allowable catch]. [l]

The populations of all large predator fish in the oceans have declined by 90% in the 50 years since modern industrial fishing became widespread worldwide.[li] Dr. Maria Salta, a biological oceanographer and lecturer in environmental microbiology in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Portsmouth, echoed this dire outlook on the state of the oceans:

It is clear that if we continue like this, in a few years time, there is not going to be much left. We are losing species every day without ever knowing about them. Sometimes humans can be like a plague to the environment. The oceanic white-tip shark populations declined by 99 percent from 1950 to 1999, making it now an endangered species. [lii]

According to an NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) report on killing marine mammals in foreign fisheries, more than 650,000 marine mammals are killed or seriously injured every year in foreign fisheries after being hooked, entangled, or trapped in fishing gear.[liii] Seals, sea lions, whales, dolphins, porpoises, and others are killed due to indiscriminate fishing practices, threatening the survival of numerous marine mammal populations.

Seabirds, such as terns and penguins, are starving because industrial fisheries are catching their food sources. The diminishing food supply for seabirds has caused a 70% population decline over the last 70 years. Since the 1970s and 80s, nearly 50% of terns, frigate birds, and 25% of penguins are gone. Not only are seabirds starving to death trying to compete with massive fishing vessels, but they are also getting tangled in fishing gear and dying from eating the plastic waste that has flooded into the oceans.[liv]

Longline fishing alone is estimated to kill 160,000 to 320,000 seabirds every year.[lv] Bristling with hooks and longlines, which can be up to 80 miles long, unintentionally traps, drowns, and harms seabirds, as well as turtles, dolphins, and other marine life. Industrial fishing vessels accidentally kill tens of thousands of albatrosses each year, bringing them ever closer to extinction.[lvi] The population of leatherback turtles has plummeted by 97% over the last 30 years in no small measure due to longline fishing. Every year, tens of thousands of sea turtles drown after getting snagged due to longline fishing.

“Outside national waters, in the high seas, it is essentially a no man’s land when it comes to protecting sensitive environments and their inhabitants,” says Paul Snelgrove, a deep-sea biologist at Memorial University in St John’s, Canada. “It is a highly unsatisfactory state of affairs.”[lvii]

In 2018, there were 4.56 million fishing vessels, with 67,800 of them 24 meters (78 feet) or longer.[lviii] Fishing operations have expanded to, quite literally, every corner of the ocean over the last 100 years. Technological advances have enabled humans to find and catch every single fish in the sea, no matter where they are located on the planet. A huge problem associated directly with overfishing is the widespread use of trawling. Doctor Maria Salta comments,

It’s the equivalent of forest clear-cutting, but in the ocean, because when they trawl the entire bottom, whatever is there, is removed from the environment and changes the entire ecosystem. Biomass of the deep sea is in sharp decline because of trawling.[lix]

The rapid depletion of fish stocks on continental shelves helped create pressure to find alternative fishing grounds. At the end of the twentieth century, fleets of ships began fishing seamounts, which are mountains that rise from the ocean seafloor and do not quite reach the ocean’s surface. These more remote fishing areas are more easily prone to fish stock collapse as the fish targeted over seamounts are typically long-lived, slow-growing, and slow-maturing. Many of these fisheries more closely resemble mining operations than sustainable fisheries, with targeted fish stocks showing signs of overexploitation within a short period from the start of fishing. This has been the case for the orange roughy fisheries off New Zealand, Australia, Namibia, and the North Atlantic.[lx]

...on seamounts and on continental slopes, where virgin communities are fished, similar dynamics of extremely high catch rates are observed, which decline rapidly over the first 3–5 years of exploitation.[lxi]

The problem is worsened by the dangers of trawling, which damages seamount surface communities. In addition, the fact that many seamounts are located in international waters makes proper monitoring nearly impossible.

It is widely accepted that seamounts are fragile habitats. Trawl gear is today being deployed across steeply irregular, and often boulder-strewn, sea floor surfaces at depths typically lying between 500 and 1000/2000m [1640 and 3280/6560 feet]. Netting caught during passage across the seabed can cause considerable damage to seabed environments (e.g., deep water coral reefs), and if not recovered, may remain there, out of sight, and continue ghost fishing almost indefinitely. The potential magnitude of disturbance to seabed environments can be likened ‘forest clear cutting.’[lxii]

It takes an average of only 4 years for seamount fisheries to collapse and 5 to 15 years after the collapse for recovery, making these seamount fisheries unsustainable.[lxiii]

Expanding fishing areas, using bigger vessels, better nets, and new technology for spotting fish are not bringing the world’s fleets more significant returns. These technological advances put immense pressure on fish stocks and leave fewer regions out of reach where fish can reproduce unmolested, thus worsening the effects of over-harvesting.

Fisheries experts trying to quantify illegal fishing along the African coast say tens of thousands of tons of fish are stolen by foreign fishing vessels just along Senegal’s coast alone.[lxiv] This ongoing practice of fishing fleets moving their operations from depleted areas to new areas causes a long-term decline in global catches as overfishing spreads.[lxv]

Slavery on the high seas

When there are too few fish to catch in an area, fishing vessels venture farther from shore into deeper waters, staying out at sea longer. Investigative reports reveal how the fishing industry, especially in Southeast Asia, coerces or forces men against their will into modern-day slavery in vast fishing fleets. Men sometimes remain at sea for years on end. An exploited migrant worker from Myanmar describes the living conditions onboard illegal Thai trawlers:

When working, we invest our whole life. We’re in their hands, and there is nothing we can do about it. When they give orders, we have to follow. It’s quite dangerous. We have to eat when they tell us to, sleep when they tell us to. There’s absolutely no excuse. When I make a mistake, they beat me with a metal rod.[lxvi]

Impoverished villagers are offered what seems to be a well-paying fishing job but then incur debt for food and lodging. According to Doctor Jessica Sparks, course director at the Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health at Tufts University, who researches the connections between fishing stock declines worldwide and forced labor on the open seas,

That’s called debt bondage. There are stories of fisherman being out at sea for five to ten years, without ever setting foot on land, getting transferred from one vessel to another at sea. There’s a lot of physical violence, sexual violence, mental violence—people getting thrown overboard to fish for sharks.[lxvii]

According to a study by the anti-trafficking group International Justice Mission (IJM), more than a third of migrant fishermen in Thailand have been victims of trafficking.[lxviii] Thailand is the world’s third-largest seafood exporter and, as of 2014, has more than 42,000 active fishing vessels with more than 172,000 people employed as fishermen. Three-quarters of migrants working on Thai fishing vessels are in debt bondage and struggle to pay that obligation. They are routinely underpaid and physically abused.

Thailand’s multibillion-dollar seafood sector came under fire in recent years after investigations showed widespread slavery, trafficking and violence on fishing boats and in onshore food processing factories.[lxix]

Most of these fishermen work at least 16 hours a day, and only 11% were paid the legal monthly minimum of $272 per month. Working 16 hours, 7 days a week, means these virtual slaves are paid just over $0.50 per hour. One indebted fisherman owed a debt to his supervisor fisherman’s brother, “I fear for my life as he has killed in front of me before. I don’t dare to run. He would kill my children.”[lxx]

Aung Ye Tun was 17 years old when he was tricked and forced to work on a Thai fishing boat under slave-like conditions.[lxxi] He described how they worked around the clock with only half an hour’s rest a day, and anyone caught sleeping without permission would be beaten. Food was scarce, and some of them resorted to eating raw squid. For five years, he was exploited along with other trafficked youths. “When the situation was at its worst, we used to say it was hell,” he said. The big boats work for three months without enough food supplies and let the workers starve. Some people take their own lives by jumping into the water.

According to the UK-based Business and Human Rights Resource Center (BHRRC), little has been done to combat slavery in the tuna supply chain.[lxxii] As of 2019, about 80% of the world’s biggest canned tuna brands do not know who caught their fish, putting workers in the industry at risk of exploitation and slavery. According to Amy Sinclair of BHRRC,

Modern slavery is endemic in the fishing industry, where the tuna supply chain is remote, complex and opaque. Yet despite years of shocking abuses being exposed, tuna companies are taking little action to protect workers.[lxxiii]

A 2015 investigation found men held in cages who had not heard from their families in five or even ten years. Caught in perpetual debt bondage, these modern-day slaves, who are frequently beaten, must pay for food and shelter and work 22-hour days to settle that bottomless debt.[lxxiv] Investigations found that Thai captains torture their slaves, and those who resist are often murdered. A former Cambodian slave shared a typical story,

I once saw a captain grab a metal spike used to mend nets and stab a fisherman in the chest. The crew pulled a sleeping bag over his corpse and rolled it overboard.[lxxv]

Reporters following the supply chain found it ended up under labels including Iams, Meow Mix, Fancy Feast, and other types of cat food.[lxxvi] The distributors in the United States receive some of the seafood from these factories and sell it to Wal-Mart, Kroger, Albertson’s, Safeway, and others. As much as 70% of seafood for export markets is produced in developing countries where labor costs are relatively low as the risk of abuse and slavery is high. Cargo ships loaded with slave-caught seafood destined for Western markets are widespread in the industry. According to a study in Science Advances,

Seafood is made with a significant incidence of forced labor, child labor, or forced child labor in the seafood hub countries of Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Peru. In 2016, widespread forced labor in seafood work was reported in 47 countries, with incidents reported in additional countries, including New Zealand, Ireland, the United States, and Taiwan.[lxxvii]

The 2022 Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage report revealed:

128,000 fishers who are trapped in forced labour aboard fishing vessels, often at deep sea, a workplace characterised by extreme isolation, hazardousness, and gaps in regulatory oversight.[lxxviii]

Warming waters

The Gulf of Maine extends from Cape Cod in Massachusetts to Cape Sable at the southern tip of Nova Scotia. Years of strict fishing limits were instituted in this area to repopulate cod stocks. Historically, establishing fishing quotas has helped various fish stocks recover. Yet, despite these limits, this wasn’t happening with cod in the Gulf of Maine. In fact, populations were continuing to decline. As researchers investigated, they found that cod spawning and survival have been hampered by rapid, extraordinary ocean warming in the Gulf of Maine, where sea surface temperatures rose faster than anywhere else on the planet between 2003 and 2014.[lxxix] According to Dr. Simon Boxall, an associate professor of oceanography at the University of Southampton,

Cod were overfished, but we also see climate change kicking in and warming the waters, and cod, which like a cooler climate, are being pushed further north. Our cod are migrating to Iceland.[lxxx]

Andy Pershing, chief scientific officer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland, says, “We’re really in the crosshairs of climate change right now.”[lxxxi] The dramatic warming in the Gulf of Maine during the summer and early fall has extended “summer conditions” by 66 days over the last 33 years. Warming in the previous 10 years has occurred faster than 99% of the global oceans,[lxxxii] and in 2012, average water temperatures reached the highest level in the 150 years that humans have recorded them.[lxxxiii] Andrew Thomas, a professor at the University of Maine School of Marine Sciences, noted,

There are going to be winners, and there are going to be losers. If you’re a tourist and you want to swim on the beaches, a longer, warmer summer sounds fine. But there are definitely marine species that are going to have trouble adapting to that kind of change because it’s happening very rapidly.[lxxxiv]

An update in 2020 by Andrew Pershing, Ph.D., shows the warming continues.[lxxxv] Since 2010, the Gulf of Maine’s temperature has been above average at 92% and at heatwave levels for 55% of the time. Dr. Pershing comments,

Whether it’s the temperatures alone, or some of the species that come with them (e.g., recent reports of black sea bass and bonito), observations that would have surprised us a decade ago now feel expected. Like so many other parts of our lives this year, what used to be unimaginable is now a new normal.[lxxxvi]

It’s not only cod that is being affected by increasing water temperatures. According to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) researchers, about 50% of 36 fish stocks in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, many of them commercially valuable species, have been shifting northward over the last four decades. Some stocks have nearly disappeared from United States waters as they move farther offshore. Janet Nye, a postdoctoral researcher at NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, commented,

During the last 40 years, many familiar species have been shifting to the north where ocean waters are cooler, or staying in the same general area but moving into deeper waters than where they traditionally have been found. They all seem to be adapting to changing temperatures and finding places where their chances of survival as a population are greater.[lxxxvii]

A 2013 paper in the journal Nature showed that ocean warming has already affected global fisheries in the past four decades. Shifts in fish populations in most of the world’s coastal and shelf areas have significantly and positively been related to regional changes in sea surface temperature.[lxxxviii] The study’s lead author, William Cheung, an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia’s Fisheries Centre, noted,

One way for marine animals to respond to ocean warming is by moving to cooler regions. As a result, places like New England on the northeast coast of the U.S. saw new species typically found in warmer waters, closer to the tropics. Meanwhile, in the tropics, climate change meant fewer marine species and reduced catches, with serious implications for food security. We’ve been talking about climate change as if it’s something that’s going to happen in the distant future -- our study shows that it has been affecting our fisheries and oceans for decades.[lxxxix]

Farmed fish

Until recently, fish have been the only remaining important food source that is still mainly gathered from the wild rather than farmed. Yet, as the amount of global wild fish caught continues to decline, aquaculture, also known as fish or shellfish farming, has increasingly filled the gap. Because of this seafood alternative, fish consumption has continued without much public notice of wild fish stocks’ devastation. Aquaculture has grown enormously since the 1980s.[xc] By 2021, it was forecast to overtake wild-caught as the primary source of fish.[xci] As of 2020 they are nearly tied with capture fisheries contributed 90 million tonnes (51%) and aquaculture 88 million tonnes (49%).[xcii] However, aquaculture's significant adverse effects on the environment and wild fish are worth considering.

At the core of industrial food production is monoculture, which is growing single crops intensively on a large scale. Corn, wheat, soybeans, cotton, and rice are commonly grown this way. Monoculture farming relies heavily on chemical inputs such as synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Fertilizers are needed because growing the same plant in the same place year after year quickly depletes the plant’s nutrients. These crops are also susceptible to disease and pests because a lack of genetic variety makes them ecologically vulnerable. Farmers attempt to control these problems with chemicals, pesticides, and genetically modified (GMO) crops.

Aquaculture uses the same methods to achieve large-scale and profitable outputs as other industrial food production systems. When using these intense monoculture methods, aquaculture operations also experience similar types of negative consequences. The salmon farming industry uses open-net cages placed directly in the ocean, where farm waste, chemicals, disease, and parasites are released into the surrounding waters, harming other marine life.

Sea lice are small ectoparasitic copepods [small crustaceans] that attach onto the scales of fish, feeding on tissue, mucus, and sometimes blood. In naturally occurring systems, lice infestation usually occurs in adults whilst they are at sea. Since sea lice cannot survive in fresh water, they fall off the adult salmon or die when they return to freshwater spawning streams. The problem for farmed salmon is that they are confined to a limited area. If a louse originating from a wild salmon infects a farmed salmon, the farmed salmon never migrates to freshwater and so can’t shed the lice. In farmed salmon, typically kept in high densities, lice can easily increase to levels not normally experienced in the natural environment.[xciii]

Since the start of large-scale salmon farming in the 1970s, sea lice have primarily been managed using chemotherapy. This has been effective and simple to use but also creates unwanted environmental effects, occupational hazards, and drug resistance problems.[xciv]

Fish excreta [waste] and uneaten feeds from fed aquaculture diminish water quality. Increased production has combined with greater use of antibiotics, fungicides, and anti-fouling agents, which in turn may contribute to pollute downstream eco-systems.[xcv]

When over half a million or more farmed salmon are crowded in a small area, an enormous amount of fish feces and waste feed is produced. For example, in Scotland, the discharge of untreated organic waste from salmon production equals 75% of Scotland’s human population’s pollution.[xcvi] This can significantly impact the ocean bottom and surrounding ecosystems, making the farmed salmon more vulnerable to sea lice. Sea lice proliferate on salmon farms and spread to surrounding waters, attacking younger, vulnerable wild salmon as they swim in their natural environment, causing disease in the wild salmon populations.

The evidence that salmon farms are the most significant source of... sea lice on juvenile wild salmonids [a fish of the salmon family] in Europe and North America is now convincing. Farms may contain millions of fishes almost year round in coastal waters and, unless lice control is effective, may provide a continuous source of sea lice, although the amount of infestation pressure will vary over time owing to seasonal and farm management practices.[xcvii]

Another inescapable consequence of open-pen salmon farming is that predators are naturally attracted to the vast quantities of fish confined in artificial environments. Just as ranchers shoot predators, such as wolves and coyotes, salmon farmers shoot predators, such as seals and sea lions, that endanger their salmon stocks.

Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) statistics show that since 1990, the B.C. [British Columbia] industry has shot and killed more than 7,000 of our marine mammals: almost 6,000 harbour seals, 1,200 California sea lions, and 363 endangered Steller sea lions.[xcviii]

The United States imports about 86% of its seafood, about half of which is grown in aquaculture. Almost 90% of farmed fish and shellfish come from Asia.[xcix] China produces about 70% of the farmed fish in the world, employing 4.5 million fish farmers. Fish farms can be found in lakes, ponds, rivers, reservoirs, or sizeable rectangular fish ponds dug into the earth.

Fish and shellfish in Asian countries are often raised in filthy, overcrowded conditions. In China, water supplies are contaminated by sewage, industrial waste, and agricultural runoff, including pesticides. Half of the rivers in China are too polluted to even serve as a source of drinking water. Nearby coastal waters, which are also heavily fish-farmed, are polluted with oil, lead, mercury, and copper.[c] Farmers have been known to feed tilapia fish with the feces of pigs and geese to lower production costs.[ci] The heavily polluted Yangtze River, contaminated with heavy metals, fertilizers, pesticides, and weed killers, is bordered by 20,000 chemical plants[cii] and lined with fish farms. In 2007, one fish farm along that river sent about 2.7 million catfish fillets yearly to the United States through an importer in Virginia.[ciii]

In China and other countries with lax environmental standards, to keep the animals alive in these low-quality water conditions and overflowing farms, they are liberally dosed with powerful and often illegal antibiotics and pesticides. This keeps the animals living yet leaves poisonous and carcinogenic residues in seafood.[civ] The contaminated output from all of these farms also has a tremendous impact on the surrounding environment. Reservoirs used by fish farmers become toxic waste dumps because of the liberal use of animal manure, fertilizers, and antibiotics.[cv]

Industrial fish farming has destroyed mangrove forests in Thailand, Vietnam, and China, heavily polluted waterways, and radically altered the ecological balance of coastal areas, mostly through the discharge of wastewater. Aquaculture waste contains fish feces, rotting fish feed, and residues of pesticides and veterinary drugs as well as other pollutants that were already mixed into the poor quality water supplied to farmers. [cvi]

In the United States, most shrimp is imported and grown in industrial-sized, man-made ponds along the coasts of Southeast Asia and South and Central America. Thailand is the leading shrimp exporter to the United States, followed by Ecuador, Indonesia, China, Mexico, and Vietnam.[cvii] Coastal mangroves, which provide a thriving habitat for many species, are frequently demolished to make way for shrimp ponds. Almost 10% of the world’s mangrove forests have been destroyed[cviii] by the building of shrimp ponds, considered the world’s most significant cause of coastal mangrove destruction.[cix] In addition, these shrimp farms produce a tremendous amount of waste that pollutes the surrounding land and water, depleting the freshwater supply. In Bangladesh, shrimp aquaculture generates 600 metric tons (660 tons) of waste daily.[cx] After an average of seven years, the ponds, crammed with millions of shrimp, become so polluted with shrimp waste and chemicals that shrimp farmers move on to build new ponds, leaving behind abandoned wastelands.

The explosive growth of shrimp farms in Ecuador, Honduras, and Mexico has negatively impacted water quality and destroyed large areas of mangroves. Nearly 75% of the fish caught at sea hatch or breed in mangroves or rely on the intact mangrove system. The destruction of these mangroves has caused a decline in wild fish catch, with studies indicating that for every hectare of mangrove forest destroyed, an estimated 757 kilograms (1,669 pounds) of commercial fish are lost.[cxi]

In addition to their own environmental and health hazards, farmed fish are often fed large quantities of wild-caught fish. Fishmeal made from this wild-caught sea life utilizing “annihilation trawling” is used to feed farmed tiger prawns or salmon that are then sold to stores and restaurants.[cxii] According to a short film about fishing and fish meal:

By dragging small mesh nets along the bottom of the sea, the trawler pulls up virtually every living thing in its way. Everything from endangered species, such as sharks, to seahorses and sea snakes. Most of the catch consists of small fish. These are not only vital to larger fish, but if left to grow could be used as food by people living there. This is how ecosystems are destroyed, and a large number of animals, like dolphins and seabirds, can no longer find enough food.[cxiii]

Many intensive aquaculture farms use two to five times more fish feed to fatten their farmed fish than is actually produced. So, for example, it can take 2.8 pounds of wild fish to produce a pound of shrimp, 3.2 pounds to produce a pound of salmon, and 4.7 pounds to produce a pound of eel.[cxiv] So, in many instances, aquaculture, instead of reducing stress on our oceans, may actually increase it.

Ocean life collapse

The world’s oceans are under increasing stress, with nearly 6 billion metric tons (6.6 billion tons) — equal to more than the weight of 18,000 Empire State Buildings — of fish and invertebrates that have already been taken from the oceans since 1950.[cxv]

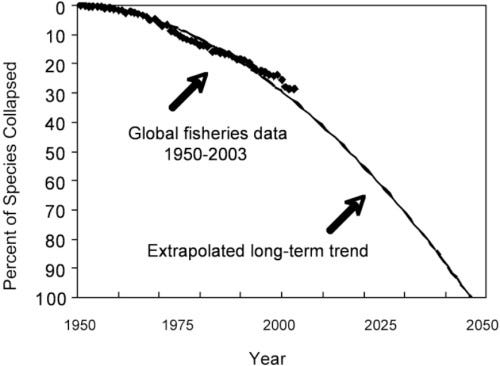

Dr. Boris Worm, a Marine Research Ecologist and Associate Professor at Dalhousie University, Canada, led an international team of researchers who found that fishery decline is closely tied to a broader marine biodiversity loss. These fisheries experts and ecologists predict that if fishing worldwide continues at its current pace, species will vanish, marine ecosystems will unravel, and there will be a global collapse of all species currently fished, possibly as soon as mid-century.

Our data highlight the societal consequences of an ongoing erosion of diversity that appears to be accelerating on a global scale. This trend is of serious concern because it projects the global collapse of all taxa [group of organisms] currently fished by the mid–21st century (based on the extrapolation of regression to 100% in the year 2048).[cxvi]

The decrease in biodiversity, or a variety of life, in the oceans, tends to reduce local fish stocks’ size and robustness. This loss of biodiversity is driving the decline in fish populations seen in large-scale studies.

“The image I use to explain why biodiversity is so important is that marine life is a bit like a house of cards,” said Dr. Worm. “All parts of it are integral to the structure; if you remove parts, particularly at the bottom, it’s detrimental to everything on top and threatens the whole structure.”[cxvii]

The global collapse of species being fished may come even earlier. According to Cyrill Gutsch, the founder of Parley for the Oceans, fish stocks’ viability may face a point of no return by 2030 if humanity keeps overfishing and does not step up efforts to reduce water pollution.

I would say the deadline of 2048 was a very optimistic one, we are already in the sixth mass extinction and we are losing 400 species every day. At Parley, we believe that if we do not turn things around in the next 10 years, we are reaching the point of no return. We are really thinking of 2030 deadline. 10 years is nothing and it means we have to organize ourselves really well. We have to innovate and prepare ourselves that we are not meeting this deadline.[cxviii]

Overfishing plays a pivotal role in this crisis by depleting fish stocks faster than they can replenish. Industrial fishing methods, including bottom trawling and over-harvesting of species at the top of the food chain such as tuna, sharks, and swordfish, as well as marine mammals like seals and whales, damage marine habitats and disrupt food webs. For example, around 40% of Atlantic stocks and 87% of Mediterranean ones are found to be fished unsustainably.[cxix] Javier López, policy manager for Oceana in Europe noted,

“Overfishing is one of the big threats currently facing European seas alongside other major problems such plastic pollution, acidification, global warming etc. However, overfishing is the issue that can more easily be solved, as the solutions are known and are simply a matter of political will.” [cxx]

According to Callum Roberts professor of marine conservation at the University of Exeter,

“Fishing is destroying these ecosystems, we’re reducing their functionality. We’re starting to see the consequences — jellyfish explosions, harmful algae blooms — these are signs of ocean dysfunction.”[cxxi]

“Now we’re seeing serial collapses of fisheries around the world. Many of the species that we caught in the fifties and sixties are no longer abundant. They’re essentially economically extinct.”[cxxii]

In 1883, Professor T. H. Huxley, a nineteenth-century English biologist and anthropologist, came to the following conclusion based on what he saw as the insignificant human impact on the inconceivably enormous numbers of fish in the ocean:

I believe, then, that the cod fishery, the herring fishery, the pilchard fishery, the mackerel fishery, and probably all the great sea-fisheries, are inexhaustible; that is to say that nothing we do seriously affects the number of the fish.[cxxiii]

Ultimately, time would prove Professor Huxley wrong. The unrelenting expansion of fishing operations due to the market-driven competition for resources means that the risks of overfishing and unsustainable natural resource use are tending to increase despite efforts to promote sustainable fishing and fish farming worldwide. Fueled by increased public demand as part of a desire for a “healthy and diversified” diet, the market for fish continues to soar, rising from 9 kilograms (19.8 pounds) per year in 1961 to over 20 kilograms (44 pounds) per year in 2015.[cxxiv] Market demand for tuna is still high, and the significant overcapacity of tuna fishing fleets remains. Growing seafood demand, combined with fewer fish, inadequate traceability systems, and a vast ocean virtually impossible to patrol, provide significant incentives for those willing to catch fish illegally and funnel them into the legitimate supply chain.

Pollution, environmental degradation, climate change, diseases, and natural and human-induced disasters threaten the livelihoods of those who rely on fishing. Shrinking catches and declining fish stocks, combined with pressure from growing coastal populations, particularly affect smaller fishing communities in many developing countries, where social protection and other employment opportunities are often lacking.

Ever-expanding global aquaculture is fraught with environmental impacts that are also negatively impacting wild fish populations. With a blind emphasis on economic growth, fish farms have destroyed mangroves, polluted waterways, and created seafood contaminated with antibiotics, pesticides, heavy metals, and potentially other dangerous chemicals. They also encourage overfishing/trawling of wild-caught fish used as fishmeal.

As human populations continue to grow, so does the insatiable appetite for seafood. The fish supply has been slowly collapsing for decades as bigger and better technologies are utilized to harvest every bit of the ocean. The once “inexhaustible manna” has proven to be finite and buckling under the pressure of human activities.

Without urgent, global transformation in how we manage and protect our marine resources, the oceans face an alarming future. The unchecked strain of overfishing, pollution, and climate impacts is rapidly driving us toward a tipping point. Without change, we may soon confront the grim reality of mostly lifeless seas, devoid of fish and the biodiversity that sustains life both underwater and on land. This is not merely an environmental crisis—it’s a threat to food security, livelihoods, and the stability of our planet. The time for decisive action is now, before the "inexhaustible manna" of the oceans disappears forever.

What you can do!

Life in oceans across the entire planet is under severe pressure from human activity and faces collapse. Here are some simple steps that you can take at a personal level to make a difference.

Move away from wild-caught seafood—For decades, vast numbers of profit-seeking commercial fishing fleets, armed with ever-improving technologies, have expanded to virtually every part of the ocean. Removal of fish from the world’s oceans peaked in the mid-1990s and has been declining since, with only 6% of the world’s fish stocks not overfished or at maximum. Simultaneously, vast numbers of mammals, sharks, seabirds, turtles, and more have been decimated either directly or because these vessels leave precious little for populations to eat, causing many to starve to death. Each year, lost or discarded fishing equipment only magnifies the destruction of “ghost fishing,” devastating life across the oceans.

Largely ignored, many tens of thousands of poor people work incredibly long hours as literal slaves to supply more affluent countries with cheap seafood. Slavery, trafficking, and physical, mental, and sexual violence are all entangled with decimating life in our oceans.

With the focus on “human nutrition” and “productive jobs,” the ever-increasing demand for fish[cxxv] continues to decimate life in the oceans. The human notion that there is no ceiling in the endless “sustainability” of the market ignores all other life on the planet. It could result in a mostly fishless ocean by mid-century or even as early as within 10 to 20 years.

Switch from fish to a primarily plant-based diet—It can supply a person with plenty of protein and nutrients. Eat foods such as quinoa, lentils, chickpeas, kidney beans, tempeh, broccoli, nuts, and nut butter to get proper, healthy amounts of protein.[cxxvi] Eat foods such as chia seeds, Brussels sprouts, hemp seeds, walnuts, and flax seeds to get healthy omega-3 fatty acids.[cxxvii] Omega-3 fatty acids (DHA and EPA) are available from sustainably grown algae and seaweed.

Move away from farmed seafood—Aquaculture continues to grow across the globe with devastating environmental impacts such as destroying mangroves and local aquatic environments. Using “annihilation trawling” to scoop up everything in the oceans to make fishmeal to feed farmed fish is an enormously destructive practice, wiping out entire ecosystems. Because it requires three times or more of the weight of wild fish to produce farmed fish for people to eat, it makes this an environmentally unsustainable practice. As recommended, change to a primarily plant-based diet when moving away from eating wild-caught fish.

Choose sustainable seafood—If you decide to eat seafood, choose the most sustainable fish. Use the Good Fish Guide from the Marine Conservation Society or other resources to determine the most sustainable fish.

Avoid industrial-raised foods—Indiscriminately caught fish is turned into fishmeal to feed fish, chicken, or other livestock. When consuming animal products, purchase those that use organic and sustainable methods. Switching to a primarily plant-based diet reduces the probability of inadvertently using products that destroy our oceans.

[i] Farley Mowat, Sea of Slaughter, 1984, Key Porter Books Limited, Toronto Canada, p. 208.

[ii] Steve Nicholls, Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery, 2009, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, p. 39.

[iii] Farley Mowat, Sea of Slaughter, 1984, Key Porter Books Limited, Toronto Canada, p. 153.

[iv] Baron De Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, Volume I, 1905, Chicago, A. C. McClurg & Co., p. 27.

[v] The Penny Cyclopaedia of The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, 1838, p. 288.

[vi] A Dictionary of Mechanical Science, Arts, Manufactures, and Miscellaneous Knowledge, 1827, London, p. 33.

[vii] The Nordic Fisheries in the New Consumer Era: Challenges Ahead for Nordic Fisheries Sector, April 1998, p. 54.

[viii] David Able, “Something new in the chill, salt air: Hope,” The Boston Globe, August 6, 2016, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/08/06/after-years-decline-cod-and-community-rebound-newfoundland/oNxKF14RpE47yc65OOAy6O/story.html

[ix] Tim Hirsch, “Cod's warning from Newfoundland,” BBC News, December 16, 2002, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2580733.stm

[x] Steve Nicholls, Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery, 2009, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, p. 39.

[xi] Rosa Garcia-Orellan, Terranova: The Spanish Cod Fishery on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in the Twentieth Century, 2010, p. 115.

[xii] Ashley Strub, and Daniel Pauly, “Atlantic cod: past and present,” The Sea Around Us Project Newsletter, March/April 2011, p. 1.

[xiii] Steve Nicholls, Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery, 2009, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, p. 39.

[xiv] Gib Brogan, “A Knockout Blow for American Fish Stocks,” The New York Times, July 7, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/07/opinion/a-knockout-blow-for-american-fish-stocks.html

[xv] Ashley Strub, and Daniel Pauly, “Atlantic cod: past and present,” The Sea Around Us Project Newsletter, March/April 2011, p. 3.

[xvi] Rögnvaldur Hannesson, “Stock crash and recovery: The Norwegian spring spawning herring,” Economic Analysis and Policy, vol. 74, June 2022, pp. 45-50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.01.007

[xvii] Steve Nicholls, Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery, 2009, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, p. 13.

[xviii] Farley Mowat, Sea of Slaughter, 1984, Stackpole books, Mechanicsburg, PA, p. 167.

[xix] Steve Nicholls, Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery, 2009, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, p. 16.

[xx] Mowat, Farley, Sea of Slaughter, 1984, Stackpole books, Mechanicsburg, PA, p. 168.

[xxi] Patrick Whittle, “Conservationists: Imperiled Atlantic Salmon Decline Worsens,” US News and World Report, June 18, 2017, https://www.usnews.com/news/news/articles/2017-06-18/conservationists-imperiled-atlantic-salmon-decline-worsens

[xxii] Monte Burke, “Endangered Atlantic Salmon Are Facing A New And Potentially Devastating Threat,” Forbes, June 14, 2013, https://www.forbes.com/sites/monteburke/2013/06/14/endangered-atlantic-salmon-are-facing-a-new-and-potentially-devastating-threat

[xxiii] Michael Dadswell, Aaron Spares, Jeffrey Reader, Montana McLean, Tom McDermott, Kurt Samways and Jessie Lilly, “The Decline and Impending Collapse of the Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) Population in the North Atlantic Ocean: A Review of Possible Causes,” Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, 2021, p. 31., https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2021.1937044

[xxiv] “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), p. 43, www.fao.org

[xxv] Amitav Ghosh and Aaron Savio Lobo, “Bay of Bengal: depleted fish stocks and huge dead zone signal tipping point,” January 31 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jan/31/bay-bengal-depleted-fish-stocks-pollution-climate-change-migration

[xxvi] Inam Ahmed and Sohel Parvex, “Fish stock set to crash,” The Daily Star, August 7, 2010, http://www.thedailystar.net/news-detail-149731

[xxvii] Abul Kalam Azad and Charlotte Pamment, “Bangladesh overfishing: Almost all species pushed to brink,” BBC, April 16 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52227735

[xxviii] Amitav Ghosh and Aaron Savio Lobo, “Bay of Bengal: depleted fish stocks and huge dead zone signal tipping point,” January 31, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jan/31/bay-bengal-depleted-fish-stocks-pollution-climate-change-migration

[xxix] James H. Tidwell, and Geoff L. Allan, “Fish as food: aquaculture’s contribution - Ecological and economic impacts and contributions of fish farming and capture fisheries,” European Molecular Biology Organization Reports, 2001, vol. 2, no. 11, pp. 958-962.

[xxx] Andrew Jacbos, “China’s Appetite Pushes Fisheries to the Brink,” New York Times, April 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/30/world/asia/chinas-appetite-pushes-fisheries-to-the-brink.html

[xxxi] Andrew Jacbos, “China’s Appetite Pushes Fisheries to the Brink,” New York Times, April 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/30/world/asia/chinas-appetite-pushes-fisheries-to-the-brink.html

[xxxii] Nicholas K. Dulvy, et al., “Extinction risk and conservation of the world's sharks and rays,” eLife Sciences, January 2014, DOI: 10.7554/eLife.00590

[xxxiii] Erik Vance, “The Push to Stop the Killing of Sharks for Their Fins,” National Geographic, June 2016, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/07/shark-fin-soup-campaign-illegal

[xxxiv] Rhian Deutrom, “Aussie shark population in staggering decline,” news.com.au, December 13, 2018, https://www.news.com.au/technology/science/animals/aussie-shark-population-is-staggering-decline/news-story/49e910c828b6e2b735d1c68e6b2c956e

[xxxv] “Sharks at risk of extinction from overfishing, say scientists,” The Guardian, March 2, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/mar/02/sharks-risk-extinction-overfishing-scientists

[xxxvi] “100 million sharks killed each year, say scientists,” The Guardian, March 1, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/mar/01/100-million-sharks-killed-each-year

[xxxvii] “Oceanic shark and ray populations have collapsed by 70 percent over 50 years,” National Geographic, January 27, 2021, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2021/01/oceanic-sharks-and-rays-collapsed-by-seventy-percent

[xxxviii] “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), p. 38, www.fao.org

[xxxix] James Wilt, “Global Fish Stocks Are in Even Worse Shape Than We Thought," The Vice, December 15, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/global-fish-stocks-are-in-even-worse-shape-than-we-thought

[xl] Christopher Pala, “Official statistics understate global fish catch, new estimate concludes,” Science Magazine, January 19, 2016, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/01/official-statistics-understate-global-fish-catch-new-estimate-concludes

[xli] Keiran Kelleher, Discards in the world’s marine fisheries - An update, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2005

[xlii] Ecological Effects of Fishing - NOAA's National Ocean Service

[xliii] Jamail Dahr, “Global Fisheries Are Collapsing—What Happens When There Are No Fish Left?” Alternet, April 17, 2016, http://www.alternet.org/environment/global-fisheries-are-collapsing-what-happens-when-there-are-no-fish-left

[xliv] Dirk Zeller, et al., “Global marine fisheries discards: A synthesis of reconstructed data,” Fish and Fisheries, 2017, DOI: 10.1111/faf.12233

[xlv] “Ten million tons of fish wasted every year despite declining fish stocks,” Science News, June 26, 2017, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/06/170626131743.htm

[xlvi] Rebecca Kessler, “‘Annihilation trawling’: Q&A with marine biologist Amanda Vincent,” Mongabay, March 27, 2018, https://news.mongabay.com/2018/03/annihilation-trawling-qa-with-marine-biologist-amanda-vincent

[xlvii] “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), p. 47, www.fao.org

[xlviii] Neslen Arthur, “Global fish production approaching sustainable limit, UN warns," The Guardian, July 7, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jul/07/global-fish-production-approaching-sustainable-limit-un-warns

[xlix] Louisa Gairn, “Fish stocks are in far worse shape than you think, say, scientists,” We Are Aquaculture, August 29, 2024, https://weareaquaculture.com/news/fisheries/fish-stocks-are-in-far-worse-shape-than-you-think-say-scientists

[l] Louisa Gairn, “Herring stocks on brink of collapse in North Atlantic, says advocacy group,” We Are Aquaculture, March 21, 2024, https://weareaquaculture.com/news/aquaculture/herring-stocks-on-brink-of-collapse-in-north-atlantic-says-advocacy-group

[li] Ransom A. Myers and Boris Worm, “Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities,” Nature, May 15, 2003, vol. 423

[lii] Jamail Dahr, “Global Fisheries Are Collapsing—What Happens When There Are No Fish Left?” Alternet, April 17, 2016, http://www.alternet.org/environment/global-fisheries-are-collapsing-what-happens-when-there-are-no-fish-left

[liii] Zak Smith, et al., “Net Loss: The Killing of Marine Mammals in Foreign Fisheries,” NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) Report, January 2014

[liv] “Industrial fisheries are starving seabirds all around the world,” Phys.org, December 6, 2018, https://phys.org/news/2018-12-industrial-fisheries-starving-seabirds-world.amp

[lv] Orea R. J. Anderson, et al., “Global seabird bycatch in longline fisheries,” Endangered Species Research, vol. 11, 2011, pp. 91-106, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00347

[lvi] Karen McVeigh, “Industrial fishing ushers the albatross closer to extinction, say researchers,” The Guardian, January 31, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/31/industrial-fishing-ushers-albatross-closer-to-extinction-say-researchers

[lvii] Robin McKie, “The oceans’ last chance: ‘It has taken years of negotiations to set this up’,” The Guardian, August 5, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/aug/05/last-chance-save-oceans-fishing-un-biodiversity-conference

[lviii] “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), p. 7, www.fao.org

[lix] Jamail Dahr, “Global Fisheries Are Collapsing—What Happens When There Are No Fish Left?” Alternet, April 17, 2016, http://www.alternet.org/environment/global-fisheries-are-collapsing-what-happens-when-there-are-no-fish-left

[lx] Morato Gomes, Telmo Alexandre Fernandes, and Pauly, Daniel, Seamounts: Biodiversity and Fisheries. Fisheries Centre Research Reports, 2004 vol. 12, no. 5, p. 61.

[lxi] Ransom A. Myers and Boris Worm, “Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities,” Nature, May 15, 2003, vol. 423, p. 282.

[lxii] Murray R. Gregory, “Environmental implications of plastic debris in marine settings—entanglement, ingestion, smothering, hangers-on, hitch-hiking and alien invasions,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2009, vol. 364, p. 2015, doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0265

[lxiii] Morato Gomes, Telmo Alexandre Fernandes, and Pauly, Daniel, Seamounts: Biodiversity and Fisheries. Fisheries Centre Research Reports, 2004 vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 63-64.

[lxiv] Andrew Jacbos, “China’s Appetite Pushes Fisheries to the Brink,” New York Times, April 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/30/world/asia/chinas-appetite-pushes-fisheries-to-the-brink.html

[lxv] Richard Black, “‘Only 50 years left’ for sea fish,” BBC News, November 2, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6108414.stm

[lxvi] “Grinding Nemo - a film about fish meal,” YouTube,

[lxvii] Taylor Mcneil, “Overfishing and modern-day slavery,” Phys.org, October 12, 2018, https://phys.org/news/2018-10-overfishing-modern-day-slavery.html

[lxviii] Zoe Tabary, “Trafficking, debt bondage rampant in Thai fishing industry, study finds,” Reuters, September 21, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trafficking-thailand-fishing-idUSKCN1BW2XP

[lxix] Zoe Tabary, “Trafficking, debt bondage rampant in Thai fishing industry, study finds,” Reuters, September 21, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trafficking-thailand-fishing-idUSKCN1BW2XP

[lxx] Zoe Tabary, “Trafficking, debt bondage rampant in Thai fishing industry, study finds,” Reuters, September 21, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trafficking-thailand-fishing-idUSKCN1BW2XP

[lxxi] Desmond Ng, “Thailand’s seafood slavery: Why the abuse of fishermen just won’t go away,” Channel News Asia, June 13, 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/cnainsider/thailand-seafood-slavery-why-abuse-fishermen-will-not-go-away-12831948

[lxxii] Lin Taylor, “Canned tuna brands found failing to combat slavery in supply chains,” Reuters, June 3, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-labour-fish-idUSKCN1T41AD

[lxxiii] Lin Taylor, “Canned tuna brands found failing to combat slavery in supply chains,” Reuters, June 3, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-labour-fish-idUSKCN1T41AD

[lxxiv] “Was Your Seafood Caught By Slaves? AP Uncovers Unsavory Trade,” NPR, March 27, 2015, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/03/27/395589154/was-your-seafood-caught-by-slaves-ap-uncovers-unsavory-trade

[lxxv] “Five Reasons Slaves Still Catch Your Seafood,” NBC News, March 10, 2014, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/five-reasons-slaves-still-catch-your-seafood-n48796

[lxxvi] Robin McDowell, “AP Investigation: Slaves may have caught the fish you bought,” Associated Press, March 25, 2015, https://www.ap.org/explore/seafood-from-slaves/ap-investigation-slaves-may-have-caught-the-fish-you-bought.html

[lxxvii] Katrina Nakamura, et al., “Seeing slavery in seafood supply chains,” Science Advances, July 25, 2018, vol. 4, no. 7, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1701833

[lxxviii] Global Estimates of Modern Slavery Forced Labour and Forced Marriage,” International Labour Organization, September 2022, p. 32.

[lxxix] Marianne Lavelle, “Collapse of New England’s iconic cod tied to climate change,” Science Magazine, October 29, 2015, http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/10/collapse-new-england-s-iconic-cod-tied-climate-change

[lxxx] Jamail Dahr, “Global Fisheries Are Collapsing—What Happens When There Are No Fish Left?” Alternet, April 17, 2016, https://www.alternet.org/2016/04/global-fisheries-are-collapsing-what-happens-when-there-are-no-fish-left

[lxxxi] Colin Woodard, “Big changes are occurring in one of the fastest-warming spots on Earth,” Portland Press Herald, October 25, 2015, https://www.pressherald.com/2015/10/25/climate-change-imperils-gulf-maine-people-plants-species-rely

[lxxxii] “Summer in the Gulf of Maine Getting Longer and Stronger,” The University of Maine, September 13, 2017, https://umaine.edu/marine/2017/09/13/summer-gulf-maine-getting-longer-stronger

[lxxxiii] Colin Woodard, “Big changes are occurring in one of the fastest-warming spots on Earth,” Portland Press Herald, October 25, 2015, https://www.pressherald.com/2015/10/25/climate-change-imperils-gulf-maine-people-plants-species-rely

[lxxxiv] “Summer in the Gulf of Maine Getting Longer and Stronger,” The University of Maine, September 13, 2017, https://umaine.edu/marine/2017/09/13/summer-gulf-maine-getting-longer-stronger

[lxxxv] Andrew Pershing, Ph.D., “2020 Gulf of Maine Warming Update,” Gulf of Maine Research Institute, August 13, 2020, https://gmri.org/stories/2020-gulf-maine-warming-update

[lxxxvi] Andrew Pershing, Ph.D., “2020 Gulf of Maine Warming Update,” Gulf of Maine Research Institute, August 13, 2020, https://gmri.org/stories/2020-gulf-maine-warming-update

[lxxxvii] “North Atlantic Fish Populations Shifting as Ocean Temperatures Warm,” November 2, 2009, http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/press_release/2009/SciSpot/SS0916

[lxxxviii] William W. L. Cheung, Reg Watson and Daniel Pauly, “Signature of ocean warming in global fisheries catch,” Nature, May 16, 2003, vol. 497, no. 365, doi:10.1038/nature12156

[lxxxix] “‘Fish thermometer’ reveals long-standing, global impact of climate change,” Science News, May 15, 2013, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/05/130515131552.htm

[xc] Water pollution from agriculture: a global review - Executive summary, FAO & IWMI, 2017.

[xci] Neslen Arthur, “Global fish production approaching sustainable limit, UN warns,” The Guardian, July 7, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jul/07/global-fish-production-approaching-sustainable-limit-un-warns

[xcii] “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), p. 1.

[xciii] Samantha Andrews, “Controlling the uncontrollable? Sea lice in salmon aquaculture,” sustainablefoodtrust.org, October 27, 2016, https://sustainablefoodtrust.org/articles/sea-lice-salmon-aquaculture

[xciv] O. Torrissen, et al., “Salmon lice – impact on wild salmonids and salmon aquaculture,” Journal of Fish Diseases, 2013, vol. 36, pp. 171-194, doi:10.1111/jfd.12061

[xcv] “Water pollution from agriculture: a global review,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the International Water Management Institute, 2017, p. 3.

[xcvi] Water pollution from agriculture: a global review - Executive summary, FAO & IWMI, 2017.

[xcvii] Mark J. Costello, “How sea lice from salmon farms may cause wild salmonid declines in Europe and North America and be a threat to fishes elsewhere.” Proceedings for the Royal Society B, July 8, 2009, pp. 3385–3394, doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0771

[xcviii] Jeff Matthews, “Seals And Sea Lions Pay The Price For B.C. Salmon Farming,” April 12 2017, Huffington Post CA, http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/jeff-matthews/salmon-farms-bc_b_9656554.html

[xcix] Jennifer Welsh, “The Disgusting Truth About Fish And Shrimp From Asian Farms,” Business Insider, October 23, 2012, http://www.businessinsider.com/disgusting-truths-about-asian-aquaculture-2012-10

[c] David Barboza, “In China, Farming Fish in Toxic Waters,” New York Times, December 15, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/15/world/asia/15fish.html

[ci] Irene Luo, “Are You Eating Tainted Seafood From China?” The Epoch Times, July 6, 2015, https://www.theepochtimes.com/why-you-should-beware-of-seafood-from-china_1418351.html