“From that fateful day when stinking bits of slime first crawled from the sea and shouted to the cold stars, "I am man.", our greatest dread has always been the knowledge of our mortality. But tonight, we shall hurl the gauntlet of science into the frightful face of death itself. Tonight, we shall ascend into the heavens. We shall mock the earthquake. We shall command the thunders, and penetrate into the very womb of impervious nature herself.” — Dr. Frederick Frankenstein

“It is only within the shadowy realm of ignorance that knowledge is perceived as absolute and all-encompassing.” — Sir Henry Holland, 1800s

“...nearly 90% of the decline in infectious disease mortality among US children occurred before 1940, when few antibiotics or vaccines were available.”[1]

We often experience a strong emotional response when we hear the word vaccination. The term is deeply ingrained in our collective consciousness, evoking a positive mental image tied to safety and progress. Infectious plagues were once a grim reality, and we are conditioned to believe that vaccines have all but eradicated them. The phrase “safe and effective” is frequently attached to vaccines, regardless of their ingredients, manufacturers, or necessity, continuously indoctrinating society into this positive notion.

Vaccination also stirs a deep-seated fear: the notion that if everyone doesn’t comply, the devastating plagues of the past will return, leaving millions to perish in the streets. But is this perception grounded in truth—or is it simply a modern myth we’ve come to accept without question?

Data from the United States, England and Wales, Massachusetts, and other regions around the world all tell the same story: deaths from infectious diseases—measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, diphtheria, tuberculosis, typhoid, paratyphoid, and others—plummeted to zero or near zero without the widespread use of vaccines or even antibiotics. This data clearly unravels the myth and challenges the prevailing narrative.

Let’s take a closer look at one specific disease: whooping cough. Between the mid-1800s and the mid-1900s, deaths from whooping cough dropped by over 99%. In 1981, Gordon T. Stewart observed that mortality from all infectious diseases had significantly declined during this period—and whooping cough was no exception.

Historically, the dominant and obvious fact is that most, if not all, major communicable diseases have become less serious in all developed countries for 50 years or more. Whooping cough is no exception. It has behaved in this respect like measles and similarly to scarlet fever and diphtheria, in each of which at least 80% of the total decline in mortality, since records began to be kept in the United Kingdom in 1860, occurred before any vaccine or antimicrobial drugs were available and 90% or more before there was any national vaccine programme.[2]

The remarkable decline in mortality from infectious diseases before the advent of vaccines has been virtually ignored, leaving us with the prevailing belief that vaccines and antibiotics are the sole solutions to combating these illnesses. Rather than recognizing the true factors behind this dramatic reduction, the medical profession doubled down on vaccination as its primary tool. There was little interest in exploring how vastly improved human and societal health transformed infectious diseases from widespread killers to relatively minor concerns. As noted by Douglas Jenkinson when he examined 500 cases of natural whooping cough:

Most cases of whooping cough are relatively mild. Such cases are difficult to diagnose without a high index of suspicion because doctors are unlikely to hear the characteristic cough, which may be the only symptom. Parents can be reassured that a serious outcome is unlikely. Adults also get whooping cough, especially from their children, and get the same symptoms as children.[3]

But we have a vaccine that at least stops whooping cough altogether. Right?

A 2011 study by Dr. David Witt, chief of infectious diseases at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Rafael, California, found that the DTaP [Diphtheria Tetanus and attenuated Pertussis] vaccine lost effectiveness in children in as little as three years.

The whooping cough vaccine given to babies and toddlers loses much of its effectiveness after just three years—a lot faster than doctors believed... “I was disturbed to find maybe we had a little more confidence in the vaccine than it might deserve,” said the lead researcher, Dr. David Witt.[4]

The 2012 study showed that the majority of children who had whooping cough—as confirmed by laboratory testing—had been vaccinated.

Of the 132 patients 18 years of age or under at time of illness, 81% were fully vaccinated, 11% under-vaccinated, and 8% never vaccinated. Of the 103 individuals 12 years of age or younger 85% were fully vaccinated, 7% under-vaccinated, and 8% never vaccinated.[5]

Contrary to broad medical belief, the disease did not strike the unvaccinated more than the vaccinated, as is generally expected by vaccine proponents. The highest incidence of disease was actually in the 8- to 12-year-olds who had previously been fully vaccinated.

Our unvaccinated and under-vaccinated population did not appear to contribute significantly to the increased rate of clinical pertussis. Surprisingly, the highest incidence of disease was among previously vaccinated children in the eight to twelve year age group... Surprisingly, in the 2-7 and 8-12 age groups, there was no significant difference in attack rates between fully vaccinated and under- and un-vaccinated children...[6]

Some estimate that as many as one-third of adolescents and adults with a prolonged cough are infected with B. pertussis bacteria. This applies even to those who have been vaccinated or had natural disease.

It is important to note that all 13 studies of adolescents and adults with prolonged cough illnesses have found evidence of B. pertussis infection. These studies have been conducted in 6 countries and 7 geographic areas of the United States over a 16-year period. These data suggest that B. pertussis infection in adolescents and adults is endemic...[7]

Although pertussis traditionally has been considered a disease of childhood, it was well-documented in adults nearly a century ago and is currently recognized as an important cause of respiratory disease in adolescents and adults, including the elderly. Because of waning immunity, adult and adolescent pertussis can occur even when there is a history of full immunization or natural disease... Studies from Canada, Denmark, Germany, France, and the United States indicate that between 12 and 32% of adults and adolescents with a coughing illness for at least 1 week are infected with Bordetella pertussis.[8]

Why is whooping cough so widespread when a vaccine has been available since the 1940s? A 2003 study showed that the vaccine was nowhere near as effective as generally believed. Although the vaccination rate in New Zealand was at least 80%, the effective protection against the disease may have been as low as 33%, which indicates that the vaccine has a high failure rate.

The obtained figures indicate that in New Zealand the effective vaccination rate against pertussis is lower than 50%, and perhaps even as low as 33% of the population. These figures contradict the medical statistics which claim that more than 80% of the newborns in New Zealand are vaccinated against pertussis. This contradiction is due to the mentioned unreliability of the available vaccine. The fact that the fraction of immune population obtained here is considerably lower than the fraction of vaccinated population implies a high level of vaccination failure.[9]

How many whooping cough shots did children get when you were growing up? Now we are in a situation where whooping cough vaccines are pretty much a regular event, cradle to grave, and the incidence of clinical whooping cough today—in the most heavily vaccinated populations—is increasing, inciting panic where the drug-sponsored media ramps up unnecessary fear. Most countries consider the use of whooping cough vaccines a success.

Yet occasionally, doctors publish statements like:

Despite high levels of vaccination coverage, pertussis circulation cannot be controlled at all. The results question the efficacy of the present immunization programmes.[10]

Or:

The time interval between outbreaks of pertussis was not changed by the introduction of the pertussis vaccine in New Zealand in 1945. Between 1873 and 1944 the average time interval between peak epidemic years was 3.9 years and between 1945 and 2004 it was 3.5 years (p=0.26 for comparison of mean inter-epidemic time interval 1873–1944 vs 1945–2004). This implies that the introduction of pertussis vaccine and the immunization of large proportions of the birth cohort each year has had no impact on the circulation of Bordetella pertussis, the bacteria that causes virtually all cases of pertussis.[11]

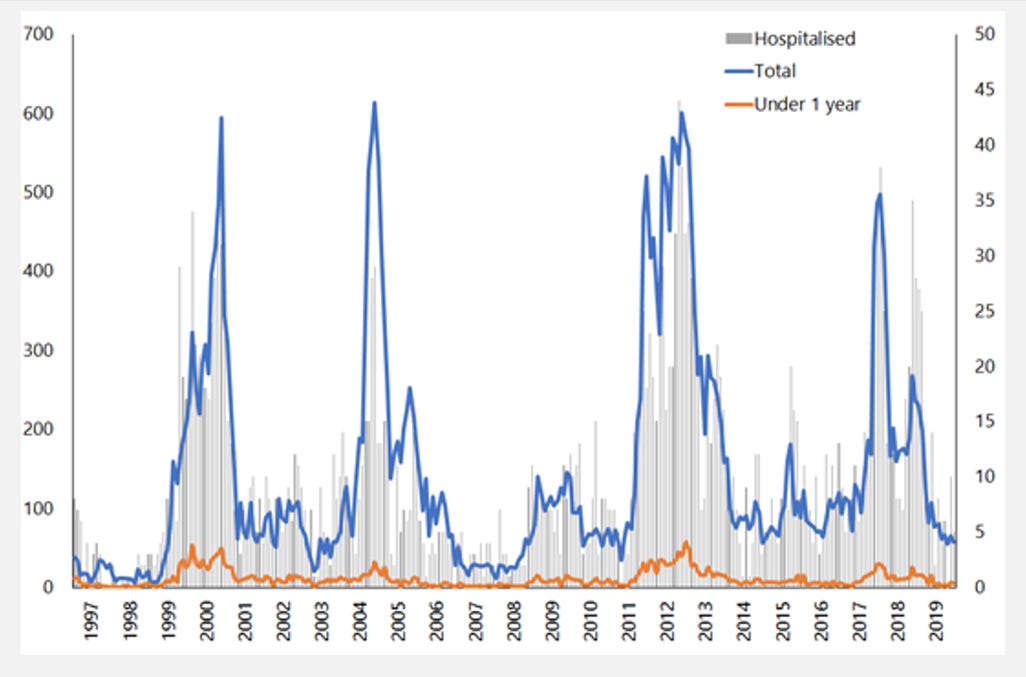

The 2020 New Zealand Immunisation Handbook[12] has this graph showing how whooping cough notifications and hospitalizations have not changed over 20 years.

Before the vaccine era, naturally acquired disease usually provided comprehensive long-term immunity because natural immunity involves a more broad-spectrum response to the entirety of the bacteria and their toxins. Remember that being immune does not stop bacteria from entering the airway. When a naturally immune person reencounters whooping cough bacteria, the body will efficiently respond and clear them from the system. This is not necessarily true of vaccinated people.

The term “original antigenic sin” (OAS) was originally coined by Dr. Thomas Francis, who became well known during the Salk vaccine era when he oversaw and interpreted the results of the largest (and most controversial) polio vaccine trial in history. He explained the phenomenon of OAS using the natural influenza virus as an example.[13]

First, let’s define how the body responds to natural infection. When a person gets an infectious disease for the first time, the body’s immune system uses its innate powers, which mostly involve pre-existing antibodies and some cellular immunity. In the process, it prepares for the future. The next time that same infectious agent comes around, the body will use its memory of the first experience to manufacture antibodies and clones of cells that recognize the invaders and react faster.

But after a vaccine is given, and then the natural microorganism comes along later, the body will act according to how it was programmed by the vaccination, and that is what is meant by original antigenic sin (OAS). Vaccination programming is very different and much less effective than natural immunity.

Dr. Cherry later sanitized the wording when referring to the phenomenon. His new terminology pointed to the same problem and was changed to “linked epitope suppression.”

In a previous study, it was observed that children who were DTaP vaccine failures had a blunted antibody response to the nonvaccine antigen ACT, whereas unvaccinated children with pertussis had a vigorous antibody response to this antigen... Linked epitope suppression applies as the immune response to the new epitopes is suppressed by the strong response to the original vaccine components.[14]

Another doctor later affirmed this in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The lesser protection provided by DTaP, both as the initial vaccine or full primary course, may be due to linked epitope suppression, when the initial exposure locks in the immune response to certain epitopes and inhibits response to other linked epitopes on subsequent exposures.[15]

Immunologists and vaccine scientists prefer not to use the term “original antigenic sin” because if they did, they would have to explain that vaccination breaches all natural, fundamental immunological processes and that vaccine immunity is vastly inferior to natural immunity and actually deleterious. As an aside, OAS was also a factor in the morbidity of the influenza vaccinated when the 2009 H1N1 infection arrived.[16],[17]

A 2021 paper[18] discussing what is now called “the airway epithelial cell landscape” starts out by saying, “It is now well accepted that the cells lining the airways constitute more than just a barrier between the external environment and the underlying mesenchyme [a type of undifferentiated connective tissue].” Those cells were previously thought to be just a physical barrier somewhat responsive to the “inhaled environment,” but now “this view has changed to one of a dynamic cellular structure encompassing a wide range of highly specialized cells…”

The paper clarifies some components of a vast semi-separate immune system, along with extensive crosstalk between neuronal and immune cells. The airways have specialized chemosensory pulmonary epithelial cells vital for regulating tissue homeostasis. There are continuous neuroimmune interactions. Not only do sensory neurons detect pathogens and trigger immune functions, but they also orchestrate and mediate respiratory responses like coughing. Developing lung immunity is critical to later developing the downstream blood “memory” antibodies, which provide backup immunity. This is important when discussing injected vaccines because injections only yield limited protection (at best) on the lung interface.

In a 2019 article titled “The 112-Year Odyssey of Pertussis and Pertussis Vaccines—Mistakes Made and Implications for the Future”, Dr. Cherry commented on the problem of misprogramming children’s immune system with DTaP causing an increased lifetime of susceptibility:

“Because of linked-epitope suppression, all children who were primed by DTaP vaccines will be more susceptible to pertussis throughout their lifetimes, and there is no easy way to decrease this increased lifetime susceptibility.” [19]

Who would have thought a “mistake” was being made with DTaP on children, causing a lifetime of increased susceptibility to whooping cough? Back in the day, when vaccines were being developed, they didn’t.

Attention has only turned to the “epithelial airway landscape” in the last 50 years. The pertussis vaccination immune program does not provide effective sterilizing immunity because it doesn’t give immunity at the lung surface, which is essential for stopping transmission and reinfection. If bacteria can attach to the airway surface and multiply, they can be spread to vulnerable people when the colonized person talks, coughs, or sneezes. The injected vaccines failed because vaccinologists thought the cells in the lung surface were just a physical barrier and all that mattered was blood antibodies. They were wrong.

It’s also instructive to know that in 2011, Stanford University acknowledged that even the immune system measured in the blood was, and still is, very superficially understood by even the most accomplished immunologists.

...“the immune system remains a black box,” says Garry Fathman, MD, a professor of immunology and rheumatology and associate director of the Institute for Immunology, Transplantation and Infection... “Right now we’re still doing the same tests I did when I was a medical student in the late 1960s...” It’s staggeringly complex, comprising at least 15 different interacting cell types that spew dozens of different molecules into the blood to communicate with one another and to do battle. Within each of those cells sit tens of thousands of genes whose activity can be altered by age, exercise, infection, vaccination status, diet, stress, you name it... That’s an awful lot of moving parts. And we don’t really know what the vast majority of them do, or should be doing... We can’t even be sure how to tell when the immune system’s not working right, let alone why not, because we don’t have good metrics of what a healthy human immune system looks like. Despite billions spent on immune stimulants in supermarkets and drugstores last year, we don’t know what—if anything—those really do, or what “immune stimulant” even means.[20]

How comforting. . .

A 2005 article[21] on pertussis had a telling introduction:

The diagnosis of pertussis is frequently missed, often because of misconceptions that whooping cough is solely a pediatric illness that has been controlled by routine childhood immunizations and that immunity resulting from pertussis disease or immunization is lifelong.

The only problem with that statement is the assumption that natural immunity is not lifelong. Before the pertussis vaccine was introduced, lengthy natural immunity was, in fact, the norm because of the natural family and community dynamics. In the 1940s, pertussis was considered only a childhood illness. If an adolescent or adult got it, everyone was astonished.

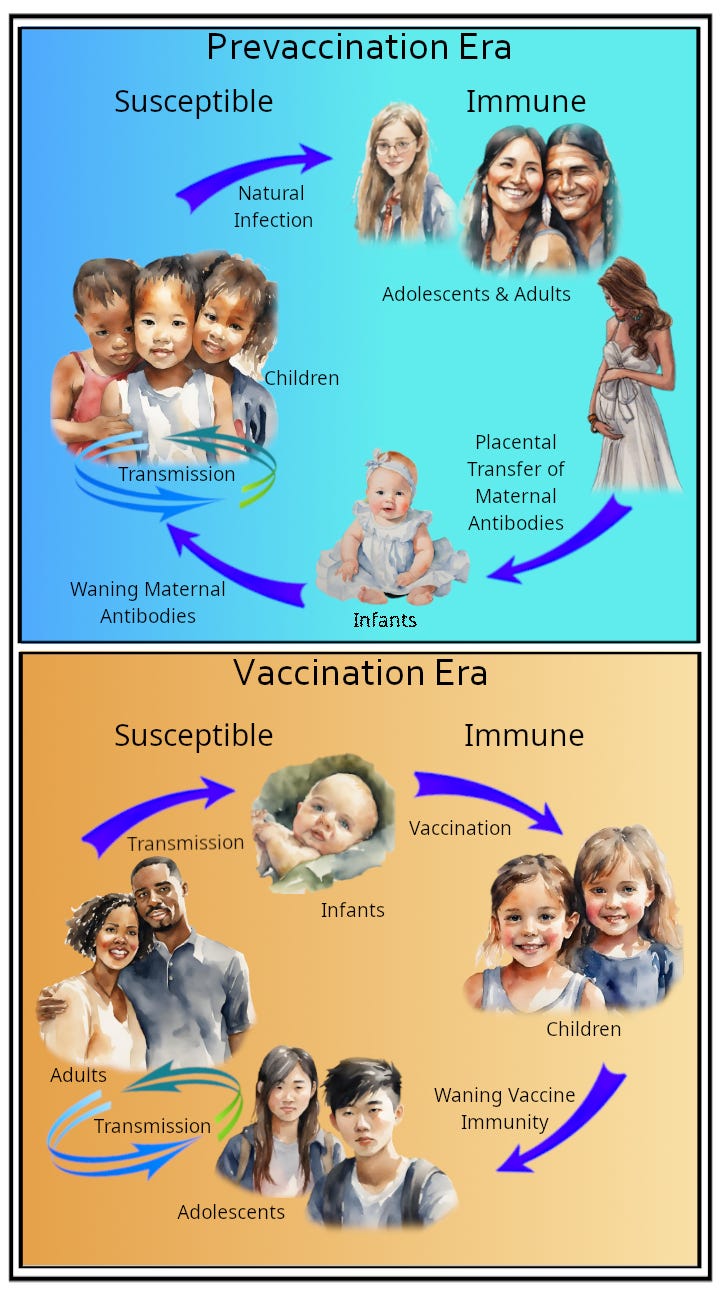

A diagram from the same article shows that only children had a clinical episode of pertussis, and generational family interactions ensured that those naturally immune from infection retained their immunity due to regular exposure to the younger generations being infected.

Vaccination turned that on its head because vaccinologists were ignorant about the immunological pathways that result in solid, durable, real herd immunity, as opposed to the fake hijacked idea of vaccine herd immunity. The ignorance of the past has brought us to the position we are in now, which is illustrated in the figure.[22] Instead of being a predominantly childhood disease, pertussis now affects adolescents and adults. Worse still, infants that once had strong maternal antibodies are now vulnerable. The pertussis vaccinations have totally changed the face of pertussis epidemiology; they have wrecked how people became immune in the first place, resulting in the vaccinated becoming walking laboratories, colonized with pertussis bacteria that mutate into new strains.

In the prevaccination era, the majority of pertussis cases occurred in children. Adults who had had pertussis as children had their acquired immunity boosted by recurrent exposures in the population, and mothers then passed protection to infants through the placental transfer of antibodies. After their use of pertussis vaccine has been established in a population, the newly immunized pediatric group is protected; an increasing proportion of cases occur in adolescents and adults, who have lost their vaccine-induced immunity, and in infants, who receive fewer passive antibodies than did infants in the prevaccination era and who are too young to be immunized according to the current immunization schedule.[23]

That process started in the 1950s due to the use of the whole cell vaccine, then accelerated once the less effective but “safer” acellular vaccine resulted in longer airway colonization upon re-exposure to pertussis bacteria.

What was the mistake vaccinologists made? They assumed they could manipulate the immune system with injections, and it would all work out okay. They made sweeping assumptions that what they knew was all there was to know. They were apparently naïve to the stepwise immunologic programming that results in durable natural immunity at the lung surface, in the lung tissue, and in the blood. In other words, a shot in the arm ended up not working in the same way as a natural infection that happens in the lungs.

The history of pertussis and its vaccines reveals the complexities and unintended consequences of altering natural immunological processes. Before widespread vaccination, natural immunity provided durable protection, reinforced by regular community exposure. However, the introduction of pertussis vaccines disrupted these dynamics, resulting in increased vulnerability among infants and a shift in disease burden to adolescents and adults. Vaccination, rather than eradicating pertussis, has inadvertently allowed the bacteria to persist and adapt, highlighting the limits of current immunization strategies.

This case underscores the importance of humility in scientific inquiry and the risks of oversimplifying the intricacies of the human immune system. While vaccines have aimed to mitigate severe disease, their long-term effects on immunity and disease epidemiology demand careful reconsideration. Moving forward, a deeper understanding of natural immunity and a commitment to respecting the body's innate complexity should guide future advancements in public health and immunology.

Vaccination is not a simple, straightforward, and cut-and-dried issue. As you have seen, developing natural immunity to infections is multi-faceted, and the human body, in general, is more complex than scientists understand. Over 200 years ago, Thomas Jefferson, American statesman, Founding Father, and the third President of the United States, understood that doctors should trust the human body and not make things worse “by conjectural experiments on a machine so complicated and so unknown as the human body.”[24]

Over the many decades since then, very few in medicine have heeded these wise words. Experimentation in almost every area of medicine has continued into the present. When the first whooping cough vaccines were proposed 100 years ago, immunologists thought that what little they knew about the immune system was all they needed to know and that whatever they invented would work. You could call it the arrogance of ignorance.

[1] “Annual Summary of Vital Statistics: Trends in the Health of Americans During the 20th Century,” Pediatrics, December 2000, pp. 1307-1317.

[2] Gordon T. Stewart, “Whooping Cough in Relation to Other Childhood Infections in 1977–9 in the United Kingdom,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, vol. 35, 1981, p. 144.

[3] Douglas Jenkinson, “Natural Course of 500 Consecutive Cases of Whooping Cough: A General Practice Population Study,” British Medical Journal, vol. 310, February 1995, p. 299.

[4] “Study: Whooping Cough Vaccination Fades in 3 Years,” Associated Press, September 19, 2011.

[5] Maxwell A. Witt; Paul H. Katz, MD, MPH; and David J. Witt, MD, “Unexpectedly Limited Durability of Immunity Following Acellular Pertussis Vaccination in Pre-Adolescents in a North American Outbreak,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, March 15, 2012.

[6] Maxwell A. Witt; Paul H. Katz, MD, MPH; and David J. Witt, MD, “Unexpectedly Limited Durability of Immunity Following Acellular Pertussis Vaccination in Pre-Adolescents in a North American Outbreak,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, March 15, 2012.

[7] James D. Cherry, MD, “The Epidemiology of Pertussis: A Comparison of the Epidemiology of the Disease Pertussis with the Epidemiology of Bordetella Pertussis Infection,” Pediatrics, vol. 115, no. 5, May 2005, p. 1425.

[8] Edward Rothstein, MD, and Kathryn Edwards, MD, “Health Burden of Pertussis in Adolescents and Adults,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, vol. 24, no. 5, May 2005, p. S44.

[9] A. Korobeinikova, P. K. Mainia, and W. J. Walker, “Estimation of Effective Vaccination Rate: Pertussis in New Zealand as a Case Study,” Journal of Theoretical Biology, vol. 224, 2003, p. 274.

[10] Maria Rosa Salle Farre, et al., “Pertussis epidemic despite high levels of vaccination coverage with acellular pertussis vaccine,” Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica, January 2015; 33 (1), pp. 27–31.

[11] Dr Cameron Grant, “An update on Pertussis immunisation in New Zealand,” 2015, https://www.researchreview.co.nz/getmedia/4fbd2266-47a4-4bee-9368-46584699ddf7/An-update-on-pertussis-immunisation-in-New-Zealand-Educational-Series.pdf.aspx?ext=.pdf, accessed February 14, 2024

[12] 2020 New Zealand Immunisation Handbook—15. Pertussis (whooping cough):

https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/immunisation-handbook-2020/15-pertussis-whooping-cough, accessed December 1, 2023

[13] T. Francis, “On the Doctrine of Original Antigenic Sin,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 104, no. 6, December 15, 1960, pp. 572–578.

[14] J. D. Cherry et al., “Antibody Response Patterns to Bordetella Pertussis Antigens in Vaccinated (Primed) and Unvaccinated (Unprimed) Young Children with Pertussis,” Clinical and Vaccine Immunology, vol. 17, no. 5, May 2010, pp. 741–747.

[15] S. L. Sheridan et al., “Number and Order of Whole Cell Pertussis Vaccines in Infancy and Disease,” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 308, no. 5, August 1, 2012, pp. 454–456.

[16] L. C. Rosella, “Assessing the Impact of Confounding (Measured and Unmeasured) in a Case-Control Study to Examine the Increased Risk of Pandemic A/H1N1 Associated with Receipt of the 2008–9 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine,” Vaccine, vol. 29, no. 49, November 15, 2011, pp. 9194–9200.

[17] R. Bodewes et al., “Annual Vaccination Against Influenza Virus Hampers Development of Virus-Specific CD8 T Cell Immunity in Children,” Journal of Virology, vol. 85, no. 22, November 2011, pp. 11995–12000.

[18] Richard J. Hewitt & Clare M. Lloyd, “Regulation of immune responses by the airway epithelial cell landscape,” Nature Reviews Immunology, January 2021, vol. 21, pp. 347–362, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33442032/, accessed February 14, 2024

[19] J. D. Cherry, MD, “The 112-Year Odyssey of Pertussis and Pertussis Vaccines—Mistakes Made and Implications for the Future,” Journal of the Paediatric Infectious Diseases Society, September 2019, pp. 334–341.

[20] B. Goldman, “The Bodyguard: Tapping the Immune System’s Secrets,” Stanford Medicine, Summer 2011.

[21] Erik L Hewlett and Kathryn M Edward, “Clinical practice. Pertussis—not just for kids,” New England Journal of Medicine, March 24, 2005 (12), pp. 1215–1222., doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp041025, PMID: 15788498, accessed February 14, 2024

[22] Ibid. Hewlett.

[23] Ibid. Hewlett.

[24] Andrew Adgate Lipscomb, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol 11, 1905, Washington DC, pp. 245–247.

Roman, as you have done consistently since Dissolving Illusions, this is an excellent piece, one of the best I've seen in terms of communicating all aspects of the problem with pertussis in an interesting and understandable fashion. Thanks very much; it will be very useful in the future.

The only thing I think would have enhanced it would have been a mention of the 2013 baboon study (https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.1314688110, by the FDA, of all people!). It made the point so clearly I put up a page on it during our battle against mandates in Maine: https://dickatlee.com/issues/health/vaccines/maine/baboons_pertussis_study.html.

Thank you, your work should be required reading in every medical profession.