Infectious Disease, Antibiotics, and Vaccination

Unlearning how medical interventions saved us

“It is not true each individual must run the gamut of measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, diphtheria, tuberculosis, and the like if proper precautionary measures be taken at the outset. Sunshine, fresh air, wholesome nutrition, exercise, rest, and the hygienic mode of living are far more effectual than all the subsequent medication in existence.”[i]

— F. M. Buckley, 1911

“You must unlearn what you have learned.”

— Yoda

When we think of infectious diseases, our minds often gravitate toward vaccines and antibiotics as the ultimate solutions for defeating these deadly threats. I used to believe that millions of lives were lost to infectious diseases every year until, long ago, scientists developed vaccines that eradicated them entirely. I’m not sure where or when I absorbed that idea, but it was a deeply ingrained certainty—something I never thought to question.

So, when I encourage people to question this premise, I’m often met with blank stares or the unmistakable “you must be a lunatic” look. I completely understand—I used to think the same way. Many others, including countless doctors over the decades, started with this “miracle of medical science” belief as well—until they took a closer look at the data and historical evidence.

National mortality data in the United States began being systematically collected in 1900. These records, along with statistics on births, marriages, and other vital events, were compiled in the United States Vital Statistics. We can better understand health trends over time by examining this data alongside the historical timeline for introducing various medical interventions.

1920: Diphtheria vaccine

1944: Penicillin mass production

1947: Streptomycin

Late 1940s: Whooping cough vaccine / England 1957

1954: BCG (Tuberculosis) vaccine

1963: Measles vaccine / England 1968

When I examined the chart based on United States Vital Statistics data, I fully expected to see dramatic declines in mortality following the introduction of various medical interventions. What I discovered instead was astonishing. As shown in the following chart, with the exception of the diphtheria vaccine, most of these interventions were introduced well after most of the mortality decline had already occurred. In the case of the diphtheria vaccine, there is an initial spike in deaths, followed by a gradual and steady decline—without any dramatic drop associated with the vaccine's introduction. It appears to have had very little impact, if any.

Before vaccines were introduced, whooping cough deaths had already declined by over 90%, and measles deaths by more than 98%. Meanwhile, deaths from scarlet fever and typhoid dropped to zero without any vaccine at all. It's important to note that antibiotics only became widely available after World War II, so they were not responsible for these declines. While this historic reduction in deaths from infectious diseases is rarely highlighted, it was acknowledged in an article published in the 2000 issue of Pediatrics.

“For children older than 1 year of age, the overall decline in mortality experienced during the 20th century has been spectacular (Fig 8). In 1900 > 3 in 100 children died between their first and 20th birthday; today, <2 in 1,000 die. Nearly 85% of this decline took place before World War II, a period when few antibiotics or modern vaccines and medications were available.”

[The percentage decrease in deaths from “3 in 100” to less than “2 in 1,000” is at least 93.3%.]

“...nearly 90% of the decline in infectious disease mortality among US children occurred before 1940, when few antibiotics or vaccines were available.”[ii]

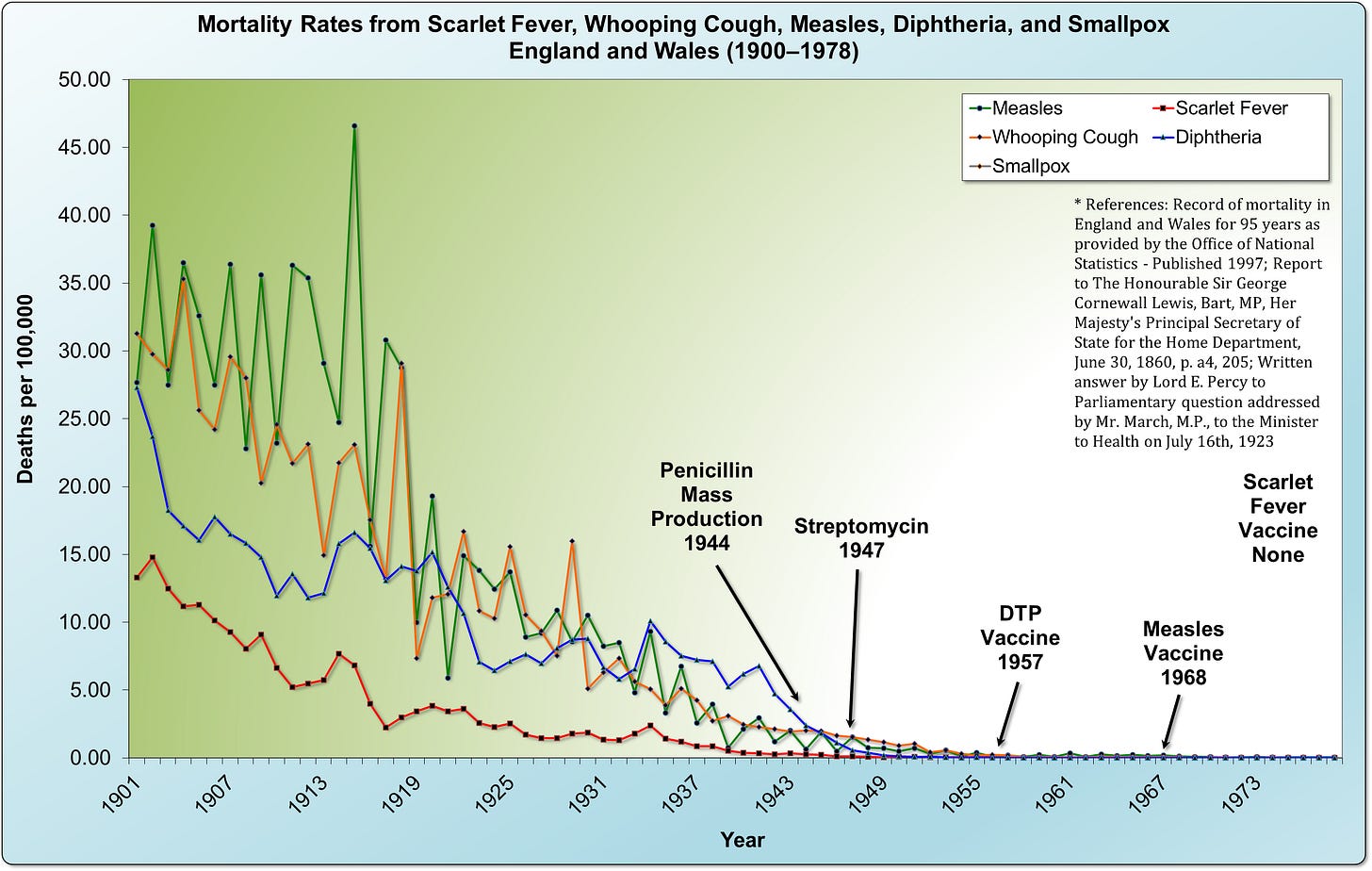

While the United States began collecting mortality data in 1900, England and Wales began much earlier, in 1838. The data from this earlier period highlights the staggering number of deaths caused by various infectious diseases, with scarlet fever claiming far more lives than the more widely recognized measles and whooping cough. Notably, the mortality rates for measles and whooping cough had already dropped by nearly 100% before the introduction of vaccines.

Around 1875, the high mortality rates began to decline, and by the mid-1900s, they had dropped to remarkably low levels. In 1914, C. Killick Millard, MD, observed this decline, emphasizing that vaccination was not the driving factor behind the reduction in smallpox deaths, as similar declines were occurring in deaths from enteric fever and scarlet fever.

“Moreover, it will be noticed that the drop in the mortality from ‘other zymotics’ was almost as striking. So much is this the case, that, without being informed, it is difficult to tell which line represents small-pox, and which ‘other zymotics.’ Obviously, causes other than vaccination must have been at work to have produced this fall in ‘other zymotics,’ and we cannot say that the same cause did not also influence the mortality from smallpox.”[iii]

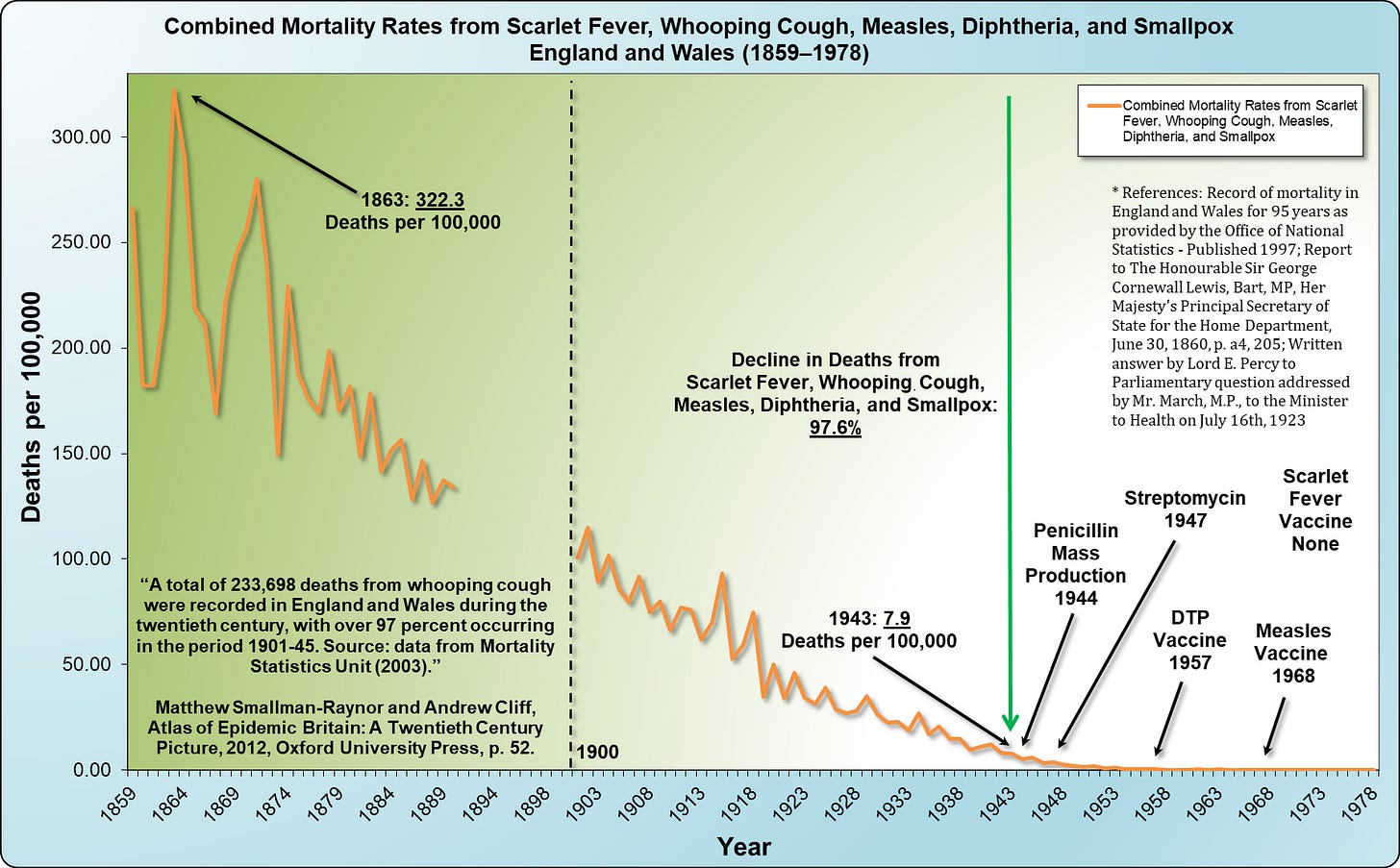

It’s fascinating to note that when the mortality rates from various infectious diseases are combined into a single rate, the data shows a steady decline beginning around 1875. By 1943, in the midst of World War II, deaths from these diseases had decreased by over 97%—a trend that occurred well before the introduction of antibiotics and vaccines. Even after their introduction, the trend continued with little impact from those interventions.

If we begin charting in 1901, it becomes still more evident that these medical interventions had little impact. By the time many of these medical measures were implemented, most of the decline in death rates had already occurred. Gordon T. Stewart highlighted this trend in 1977, specifically noting the significant reduction in whooping cough deaths.

“There was a continuous decline, equal in each sex, from 1937 onward. Vaccination [for whooping cough], beginning on a small scale in some places around 1948 and on a national scale in 1957, did not affect the rate of decline if it be assumed that one attack usually confers immunity, as in most major communicable diseases of childhood... With this pattern well established before 1957, there is no evidence that vaccination played a major role in the decline in incidence and mortality in the trend of events.”[iv]

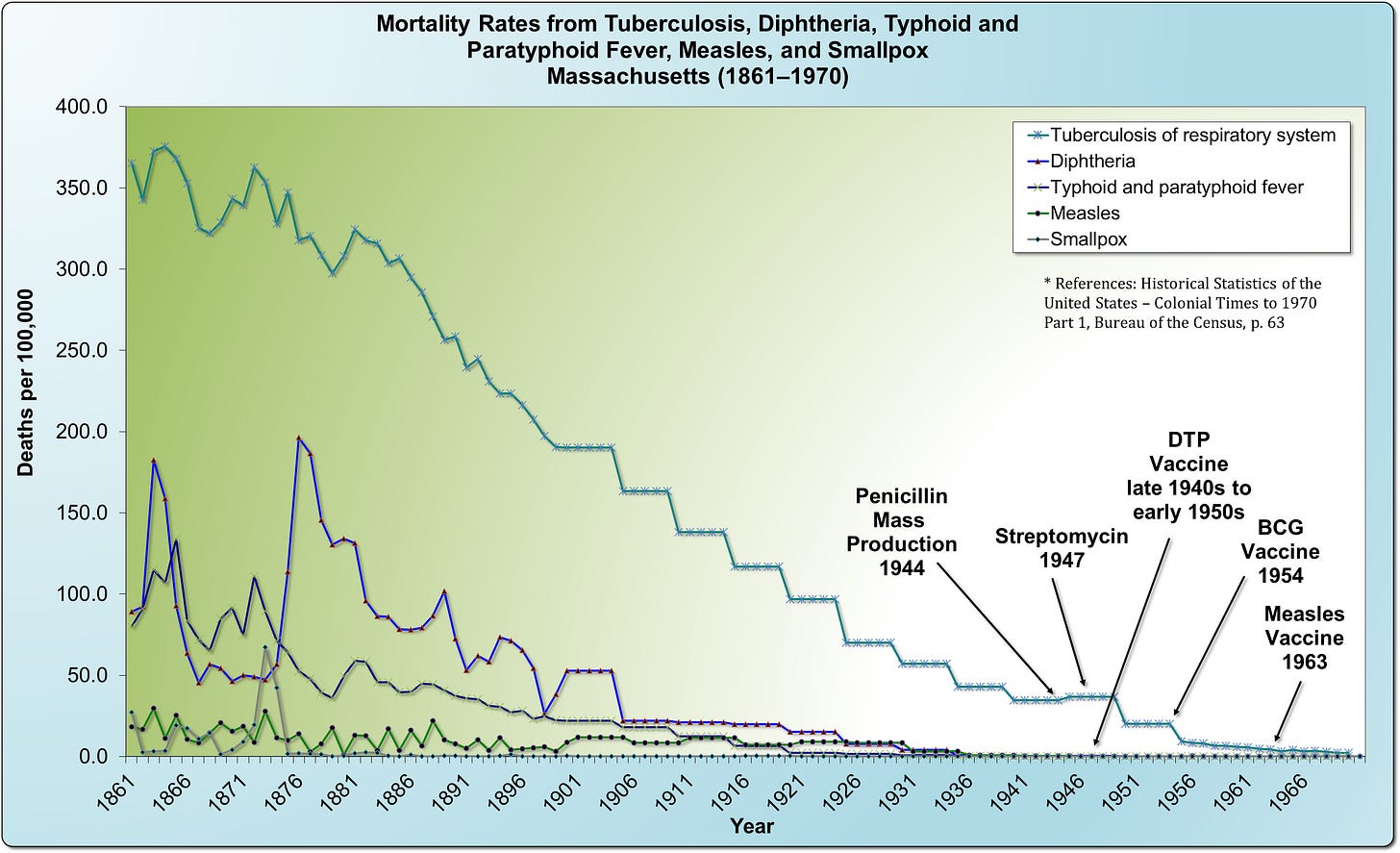

If we look at data from Massachusetts, we see that tuberculosis was one of the biggest killers during the 1800s, much larger than smallpox or measles. Again, medical interventions came in much later after much of the decline in mortality had occurred. In addition, the introduction of Streptomycin in 1947 and the BCG vaccine in 1954 had little to no impact on the trend of decline in the tuberculosis death rate.

When we examine measles deaths in Massachusetts closely, it’s clear that nearly 100% of the decline occurred before the introduction of the 1963 measles vaccine.

Today, the focus is often on measles and whooping cough vaccines and how critical they are. Yet, in both cases, the death rate had already fallen nearly 100% before these interventions. Other much more deadly diseases during the 1800s, typhoid, paratyphoid, scarlet fever, and tuberculosis, death rates have reached zero with or without an available vaccine. Despite tuberculosis being a massive killer in its day, the BCG vaccine hardly gets a mention.

We like to consider ourselves a society grounded in data and facts, where evidence drives decisions and beliefs. But when we examine the information available, we must ask: Are we truly living up to that ideal? Given the data we've just explored, do we really make choices based on what’s supported by the facts, or do we let other forces—bias, tradition, group think, profits—shape our understanding?

[i] F. M. Buckley, Oral Hygiene, vol. 1, no. 1, January 1911, pp. 183–184.

[ii] “Annual Summary of Vital Statistics: Trends in the Health of Americans During the 20th Century,” Pediatrics, December 2000, pp. 1307-1317.

[iii] C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, 1914.

[iv] Gordon T. Stewart, “Vaccination Against Whooping-Cough: Efficacy Versus Risks,” The Lancet, January 29, 1977, pp. 236, 237.

Unfortunately most people do not read books anymore and have a TikTok attention span.

Unlearning and relearning is difficult. Roman was influential for me as I began that journey five years ago. To question the efficacy of vaccination was anathema, unthinkable...yet, I persisted.

From that beginning from 'Dissolving illusions" I discovered those who question virology and the existence of viruses. It now seems to me beyond doubt that virology is a product of medical tyranny that has gripped us for over a hundred years. There is more unlearning to be done, but it remains hard, as it challenges long held dogma that we leaned, seemingly from birth.

I recommend for anyone interested this excellent paper, recently published by Denis Rancourt https://denisrancourt.substack.com/ and Correlation Research:

https://correlation-canada.org/respiratory-epidemics-without-viral-transmission/