“[measles is a] …self-limiting infection of short duration, moderate severity, and low fatality.”[1]

—Alexander D. Langmuir, MD, 1962

“Effective use of these vaccines during the coming winter and spring should insure the eradication of measles from the United States in 1967.”[2]

—David J. Sencer, MD; H. Bruce Dull, MD; and Alexander D. Langmuir, MD, March 1967

“…in 1935, I was in private practice in the coal-mining town of

Bedlington, England when the triennial measles epidemic struck. Walking or cycling, I would visit the homes of sick children, and in one day would see 20-30 new measles cases. Those were the Depression years, and the children’s diets were decidedly subnormal. It was also the days before antibiotics, so that the treatment was mostly symptomatic and ineffectual. Yet out of more than 500 sick children under my care, not a single one died.”

– Aidan Cockburn, 1971

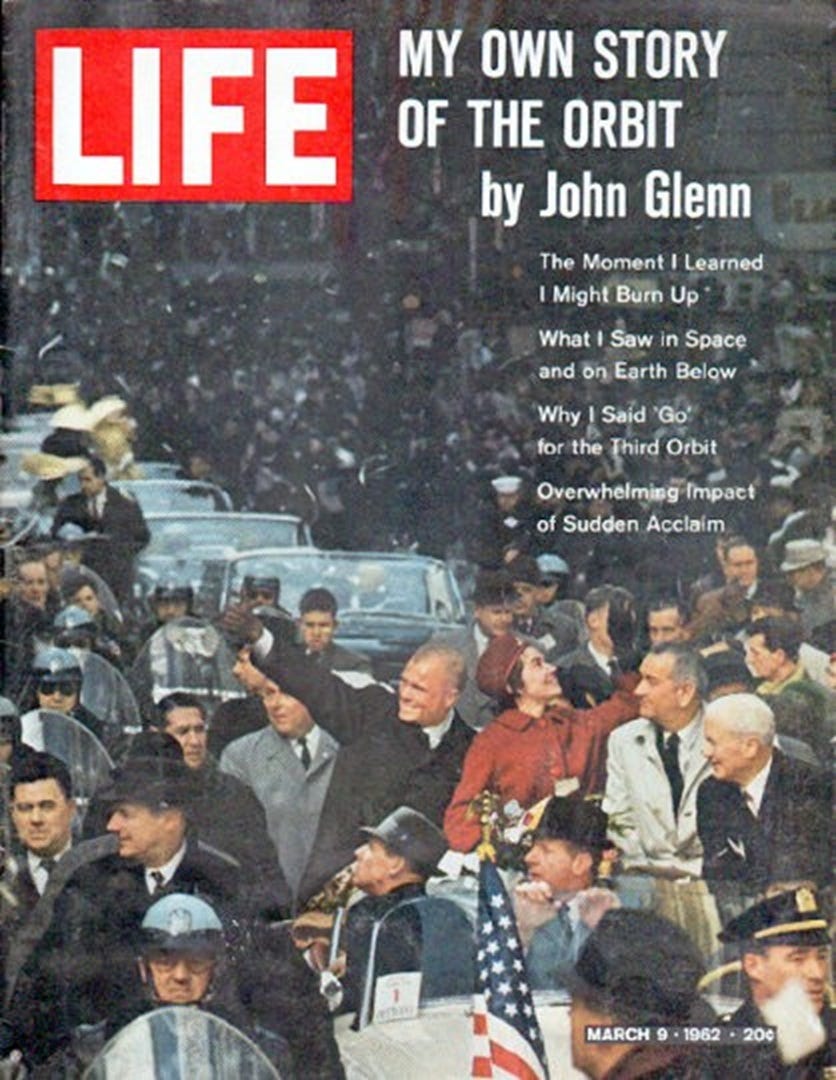

The year was 1962, a time of extraordinary global developments and cultural shifts. On February 20, astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth aboard the Mercury spacecraft Friendship 7, marking a major triumph in the Space Race and a pivotal moment in Cold War-era technological rivalry. Just months later, the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolded—a tense 13-day standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war and underscored the fragility of peace in the atomic age. In August, the world was stunned by the tragic death of Marilyn Monroe, the iconic actress whose untimely passing at age 36 sparked both heartbreak and enduring speculation over the circumstances surrounding her apparent overdose.

It was also the year before a much-publicized medical milestone—the 1963 licensing of the first widely used measles vaccine in the United States. At the time, measles was a common childhood illness, usually self-limiting, but sometimes resulting in complications or, rarely, death.

The above pie chart presents the leading causes of death in 1962.[3] But take a closer look—these categories are presented without context or nuance. They list immediate causes, but overlook the broader social, economic, and systemic conditions contributing to mortality.

Measles, with 408 deaths in 1962 (ranked #36, just 0.022% of total mortality), occurred before the vaccine was introduced—a small slice of the chart.

Meanwhile, syphilis (ranked #30, 2,811 deaths, 0.15% of the total) and scarlet fever (ranked #38, 102 deaths, 0.006% of the total), both acute infectious diseases, are rarely emphasized in public discourse—perhaps because no vaccines are administered for them.

Whooping cough, diphtheria (DTP vaccine introduced in the late 1940s), and polio (vaccine introduced in 1955)—despite the availability of vaccines—still resulted in deaths.

Perhaps most telling is tuberculosis, ranked #17, with 9,506 deaths (about 0.52% of total mortality). Though a vaccine (BCG) was available and used in many countries, it was never adopted as part of routine immunization in the United States, in part due to questions about its variable efficacy and low perceived domestic risk.

When we narrow our lens to the New England states—a region with relatively high living standards and access to healthcare—we find that measles-related mortality in 1962 was remarkably low. Just sixteen deaths were recorded across all six states:

Connecticut: 6 deaths

Maine: 4 deaths

Massachusetts: 5 deaths

New Hampshire: 0 deaths

Rhode Island: 1 death

Vermont: 0 deaths

These figures are striking when contrasted with today’s intense messaging around measles risk. The 1962 data suggest that by the early 1960s—prior to the vaccine's introduction—mortality from measles had already declined significantly in many parts of the U.S., especially in higher-income regions like New England. Improvements in nutrition, sanitation, supportive medical care, and living conditions played an essential role in reducing the fatality rate long before immunization began.

Moreover, these statistics fail to mention other crucial contributors to mortality: medical error, nutritional deficiencies, poverty, environmental exposures, and systemic inequities. By ignoring these underlying determinants of health, the pie chart simplifies complex causes of death into neat categories, raising an essential question: Do these classifications truly capture the root causes of mortality—or merely their final expression?

It’s also worth noting that public health reporting often focuses on the presence or absence of a vaccine, rather than examining the broader context of health outcomes. The emphasis on single solutions can obscure the value of holistic public health measures that include access to nutritious food, clean water, housing, education, and competent medical care.

In reflecting on the mortality data from 1962, it becomes clear that numbers alone cannot capture the full story. While the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, the data from the preceding year show a far more complex picture—one where measles accounted for a tiny fraction of deaths, even before widespread vaccination. This invites us to reconsider the oversimplified narratives we’ve come to accept and to look more deeply at the social conditions that shape health outcomes. Without acknowledging the broader social, economic, and environmental factors that influence mortality, we risk misrepresenting the challenges we face—and overlooking the most meaningful and sustainable solutions.

1. Major Cardiovascular-Renal Diseases — 968,809 deaths (53.20%)

2. Malignant Neoplasm — 278,562 deaths (15.30%)

3. Accidents — 97,139 deaths (5.33%)

4. Certain Diseases of Early Infancy — 64,205 deaths (3.53%)

5. Pneumonia — 56,564 deaths (3.11%)

6. All Other Diseases — 52,173 deaths (2.87%)

7. Other Diseases Peculiar to Early Infancy — 31,455 deaths (1.73%)

8. Diabetes Mellitus — 31,222 deaths (1.71%)

9. Birth Injuries — 28,199 deaths (1.55%)

10. Cirrhosis of Liver — 21,824 deaths (1.20%)

11. Congenital Malformations — 21,192 deaths (1.16%)

12. Suicide — 20,207 deaths (1.11%)

13. Other Bronchopulmonic Diseases — 20,072 deaths (1.10%)

14. Symptoms, Senility, and Ill-defined Conditions — 19,730 deaths (1.08%)

15. Ulcer of the Stomach and Duodenum — 12,228 deaths (0.67%)

16. Hernia and Intestinal Obstruction — 9,723 deaths (0.53%)

17. Tuberculosis — 9,506 deaths (0.52%)

18. Homicide — 9,013 deaths (0.49%)

19. Infections of Kidney — 8,744 deaths (0.48%)

20. Gastritis — 8,194 deaths (0.45%)

21. Other Infective Diseases — 5,791 deaths (0.32%)

22. Asthma — 4,896 deaths (0.27%)

23. Cholelithiasis — 4,831 deaths (0.27%)

24. Benign Neoplasms — 4,681 deaths (0.26%)

25. Bronchitis — 4,665 deaths (0.26%)

26. Infections of Newborn — 4,551 deaths (0.25%)

27. Hyperplasia of Prostate — 4,283 deaths (0.24%)

28. Influenza — 3,431 deaths (0.19%)

29. Anemias — 3,398 deaths (0.19%)

30. Syphilis — 2,811 deaths (0.15%)

31. Meningitis — 2,322 deaths (0.13%)

32. Appendicitis — 1,900 deaths (0.10%)

33. Acute Nephritis — 1,572 deaths (0.09%)

34. Delivery and other Complications of Pregnancy — 1,465 deaths (0.08%)

35. Meningococcal Infection — 649 deaths (0.036%)

36. Measles — 408 deaths (0.022%)

37. Dysentery — 323 deaths (0.018%)

38. Scarlet Fever — 102 deaths (0.006%)

39. Whooping Cough — 83 deaths (0.005%)

40. Acute Poliomyelitis — 60 deaths (0.003%)

41. Diphtheria — 41 deaths (0.002%)

[1] A. Langmuir, “The Importance of Measles as a Health Problem,” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 52, no. 2, 1962, pp. 1–4.

[2] David J. Sencer, MD; H. Bruce Dull, MD; and Alexander D. Langmuir, MD, “Epidemiologic Basis for Eradication of Measles in 1967,” Public Health Reports, vol. 82, no. 3, March 1967, p. 256.

[3] Causes of Death in the United States in 1962 — Vital Statistics of the United States, Vol II – Mortality, Part A, pp. 18-21.

The inventor of the polio vaccine, Dr. Sabin, testified before congress that the "official data shows that large scale vaccination has failed to obtain any significant improvement of the diseases against which they were supposed to provide protection."

Did anyone notice that today's measles hysteria is occurring in heavily vaccinated states and that the strain matches the one in the jab? Give a live virus, get a live virus especially in those who are probably immune compromised from mRNA jabs.