It broke one’s heart to think of man, the civiliser, wasting treasures in a few years to which savages and animals had done no harm for centuries.

– Marianne North, 1875

What we are doing to the forests of the world is but a mirror reflection of what we are doing to ourselves and to one another.

– Chris Maser, Forest Primeval: The Natural History of an Ancient Forest

We go about our days assuming the comforts we’ve built will always be there. Flip a switch, and the lights come on. Turn a knob, and clean water flows. Step outside, and food is waiting at the grocery store. Hop in a car or bus, and we’re off to wherever we need to go. With a phone or computer, information is at our fingertips. These conveniences have become so ingrained in our lives that it’s hard to imagine a time—just 100 years ago—when most of these things didn’t exist.

We trust others to fix what breaks and rely on countless systems to maintain our comfort and security. With our technology and ingenuity, we believe we can solve almost anything. Many look to governments and corporations to address the world’s most pressing issues, assuming they’re on top of things. But are they really? Are they so consumed by power, profits, and biases that they fail to see—or choose to ignore—the civilization-ending disasters looming on the horizon?

This series explores the critical issues we continue to overlook at our own peril.

In part 1, we examined the fragility of the electrical grid—the lifeblood of modern societies—and how it could vanish in an instant.

https://romanbystrianyk.substack.com/p/we-are-not-prepared

In part 2, we looked at life in our oceans, which are spiraling toward collapse under the weight of overfishing and other human activities.

https://romanbystrianyk.substack.com/p/we-are-not-prepared-47b

Now, we turn our attention to tropical rainforests, focusing on the most expansive and iconic of them all—the Amazon rainforest. These vital ecosystems, often called the "lungs of the Earth," are under relentless assault as humanity exploits them for commodities such as beef, lumber, soy, gold, and more. Already, the Amazon has lost a staggering 20% of its trees, edging dangerously close to a tipping point that could trigger its collapse. Without intervention, vast swaths of lush rainforest could transform into barren desert or scrubland. The destruction of this invaluable natural resource would be nothing short of catastrophic, threatening biodiversity, destabilizing the global climate, and imperiling the future of humanity and all life on Earth.

The world’s largest rainforest

The Amazon River Basin is an immense region made up of a mosaic of ecosystems ranging from savannas to swamps and is home to the largest contiguous rainforest on Earth. With its intricacy and vastness, the Amazon contains a magnificent diversity of life, providing a home to one out of every five mammal, fish, bird, and tree species in the world.[i] While the Amazon rainforest covers only 4% of the Earth’s surface[ii], the more than 400 mammal, 40,000 plant, and 2,500,000 identified insect species and a myriad of other invertebrates, microbial and fungal life forms, make it the most abundant habitat on the planet.[iii]

The Amazon Rainforest is defined by the vast Amazon River. It is the second-largest river in the world, flowing for more than 6,600 kilometers (4,100 miles.)[iv] It is the world’s most voluminous river, delivering more water into the oceans than the next eight biggest rivers in the world combined,[v] accounting for 15-20% of the global freshwater input into the oceans.[vi] The Amazon River Basin’s hundreds of tributaries and streams contain the largest number of freshwater fish species in the world.[vii] The more than 2,000 identified species of fish are greater than that of the entire Atlantic Ocean.[viii] While 60% of the Amazon lies in Brazil, the rainforest spans nine countries, covering about 40% of South America. It is equal in size to approximately two-thirds of the continental United States.[ix]

Known as the “Lungs of the World,” the Amazon is one of Earth’s most critical environmental filters, absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere to use in a biochemical process called photosynthesis.[x] Each leaf in the forest uses the sun’s energy and chlorophyll to convert water (H2O) and CO2 into sugars, which the plants use for energy through photosynthesis. During this process, twelve molecules of H2O and six molecules of CO2 react to form one glucose molecule (C6H12O6), six molecules of oxygen (O2), and six molecules of H2O.[xi]

Through the action of each leaf of almost 400 billion trees, made up of 16,000 tree species,[xii] the Amazon produces 20% of the world’s oxygen.[xiii] Also, by absorbing CO2, the Amazon has effectively negated the fossil fuel emissions and emissions from forest loss and degradation from the nine Amazon nations of Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela since the 1980s.[xiv] The Amazon is a vast carbon repository. Between 81 to 127 gigatons (90 to 140 billion tons) of carbon are stored in the Amazon Basin,[xv] equal to the total carbon emissions discharged into the atmosphere by all human activity over an 8 to 13-year period.[xvi]

Flying rivers

While creating energy to support its life, each tropical tree pumps a geyser of water into the atmosphere. About 760 liters (200 gallons) of water evaporates each year from all the leaves of each tree that make up the Amazon canopy, or roughly 76,000 liters (20,000 gallons) for each acre of canopy trees.[xvii] This amounts to about 18.1 billion metric tons (20 billion tons) of water emitted by all of the Amazon’s trees every day,[xviii] which is more water than the Amazon River’s daily discharge into the Atlantic Ocean and is equal in weight to over 32 million Airbus A380 Passenger Jets.[xix] This tree-generated moisture helps create the thick cloud cover that hangs over the forest. Through this process, the Amazon generates as much as 50% of its own rainfall. The remaining moisture comes from winds that bring it from the ocean.[xx]

Rainfall in much of South America depends on moisture coming from the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Westward-blowing trade winds carry water transporting it across the Amazon Basin. The clouds eventually collide with the Andes Mountains 3,200 kilometers (2,000 miles) to the west, forcing them to move south and east to the rest of the continent.[xxi] As the air stream travels west from the coast, it picks up water vapor that has evaporated from the forest and deposits it as rain further on.

It may be more than just the tropical trade winds that simply carry moisture from the east coast across the continent and then further south. According to the “biotic pump” theory, the forests, through the enormous amount of water that evaporates from the trees, create the mechanism in which the rainforest “sucks in” moist air from the ocean.[xxii] The combined force of the billions of trees in the rainforest irrigates the atmosphere, generating massive, invisible, flying rivers and creating ocean-to-land winds that pump the moisture-laden currents over the continent.[xxiii] This theory explains how deep interiors of forested continents get as much rain as the coast.[xxiv] According to Doug Sheil of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, near Oslo,

Traditionally, people have said areas like the Congo and the Amazon have high rainfall because they are located in parts of the world that experience high precipitation. But the forests cause the rainfall, and if they weren’t there the interior of these continental areas would be deserts.[xxv]

Deforestation

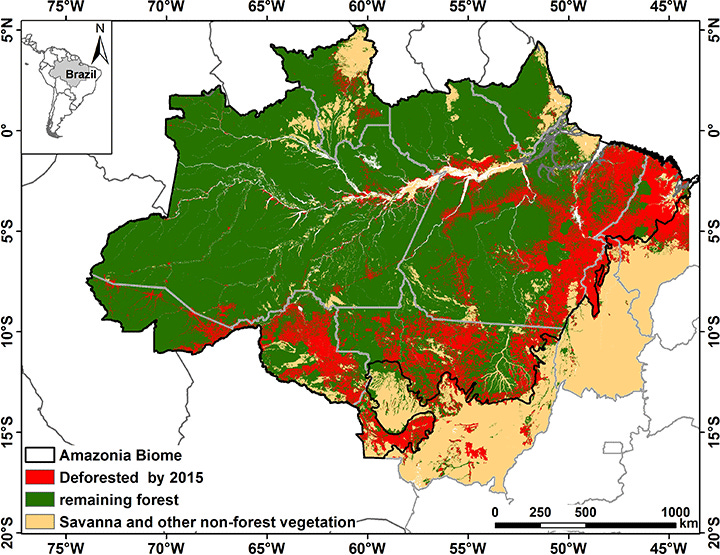

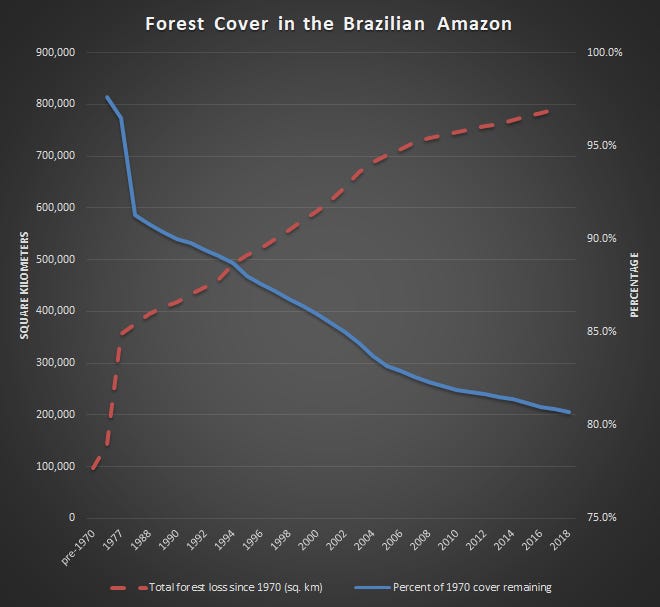

The entire Amazon rainforest is estimated to have initially covered a staggering 5.7 million square kilometers (2.2 million square miles), with approximately 12% of that area lost since the dawn of industrialization.[xxvi] By 1970, about 2.4% of the rainforest had been cleared. Since then, it has continuously been stripped of forest at varying rates.[xxvii] In 1995, loggers, cattle ranchers, and farmers set a new deforestation record, clearing 29,000 square kilometers (11,200 square miles.) In 2005, annual deforestation turned a corner, and rates began to decrease, falling to 4,575 square kilometers (1,766 square miles) by 2012 – a fall of more than 83% over eight years.[xxviii] Yet, after about a decade of decreasing deforestation rates, they reversed direction and are now growing. From August 2015 to July 2016, an estimated 7,989 square kilometers (3,085 square miles) were deforested, equal to 3 times the size of Rhode Island.[xxix]

The policy director of Greenpeace, Marcio Astrini, says among the causes of the increased deforestation were actions taken by the federal [Brazilian] government between 2012 and 2015, such as the waiving of fines for illegal deforestation, the abandonment of protected areas — that is, ‘conservation units’ and indigenous lands — and the announcement, which he calls ‘shameful,’ that the government doesn’t plan to completely stop illegal deforestation until the year 2030.

In the Brazilian Amazon, ranching has been the most common land use for over four decades and is the leading source of deforestation.[xxx] Brazil has the world’s largest commercial cattle herd and is the largest exporter of beef and leather.[xxxi] Cattle ranching accounts for about 70% of land use, requiring two acres of cleared rainforest to raise one steer.[xxxii] Other land uses, such as soybeans, sugar cane, and palm oil for biofuels, cotton, and rice, are all expanding. Brazil is second only to the United States as a global producer of soybeans.[xxxiii] Only about 6% of soybeans grown worldwide are turned directly into food products for human consumption. The rest is used as animal feed, vegetable oil, or non-food products such as biodiesel. About 75% of the world’s soy ends up as feed for chickens, pigs, cows, and farmed fish.[xxxiv]

Rainforest land is cleared for agricultural purposes. While tropical rainforest trees are well-adapted to their environment, the soils they grow in are actually very thin and lacking in nutrients.[xxxv] Farmers use slash-and-burn agriculture, burning the trees and vegetation in deforested areas to create a fertilizing layer of ash.

In the Amazon, fires aren’t naturally occurring, but rather are set after deforestation to clear the land for cattle ranching and soy farming. In 2021, more than 44,000 hectares (109,000 acres) burned in Brazil alone. A 2021 study found that the Brazilian Amazon is emitting more carbon than it captures, mostly due to fires.[xxxvi]

However, tropical high temperatures and heavy rains over time wash most minerals from the soil. Land overtaken by weeds often becomes unable to support crops in just a few years.[xxxvii] Cattle ranching's deforestation releases 308 metric tons (340 million tons) of carbon into the atmosphere every year, making up about 3.4% of current global emissions.[xxxviii]

Once trees have been removed and replaced with grass cattle pastures, they rapidly dry out during periods of limited rains, significantly increasing fire risk. Frequent fires expose the land to heavy rains, resulting in high levels of soil erosion.[xxxix] Forest fires alone destroyed more than 85,500 square kilometers (33,000 square miles) of the Amazon rainforest between 1999 and 2010, an area larger than the state of South Carolina.[xl] Since 2000, the region has been hit by three unprecedented droughts, which have led to substantially worse fires. Anja Rammig, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Germany, said,

Today, the wet season is getting wetter and the dry season drier in southern and eastern Amazonia due to changing sea-surface temperatures that influence moisture transport across the tropics. It is unclear whether this will continue, but recent projections constrained with observations indicate that widespread drying during the dry season is possible in the region.[xli]

Once a tract of land can no longer support agriculture, farmers clear adjoining forest sections, leaving swaths of unproductive, deforested land in their wake, leading to a vicious cycle of deforestation. Untouched rainforest land has little direct monetary value, but cleared pastureland can produce cattle or be sold to large-scale farmers. The cattle supply domestic and international markets with beef, leather products, and items such as rawhide dog treats. Many of these products are shipped to Europe, the Middle East, and Russia.[xlii] China is the leader in growing affluent classes, which consume increasing amounts of beef and other types of meat. In 2018, Brazil exported an estimated 1.6 million metric tons (1.7 million tons) of beef, driven by a strong demand from Hong Kong, and China imported 44% of that amount. In 2019, Brazil was expected to increase its beef export to 1.8 million metric tons (2 million tons).[xliii]

Meat from the cattle is canned, packaged and processed into convenience foods. Hides become leather for shoes and trainers. Fat stripped from the carcasses is rendered and used to make toothpaste, face creams and soap. Gelatin squeezed from bones, intestines and ligaments thickens yoghurt and makes chewy sweets.[xliv]

In the Amazon, land grabbing and illegal encroachment are rampant. A preferred method to lay claim to an area is to deforest it, making that parcel of land 5 to 10 times more valuable. After that piece of land has become unproductive, it can be sold to larger landholders, who then use massive amounts of industrial fertilizers and pesticides to make it profitable. The original settlers then move on to grab another part of the rainforest.[xlv] In addition to cattle farming, soy plantations, logging, biofuel crops, mining for diamonds, bauxite, manganese, iron, tin, copper, lead, and gold, and the construction of dams and roads all contribute to deforestation.[xlvi] In Peru, between 2005 and 2011, some 7,000 hectares (27 square miles) of Amazon forest were leveled to create three palm oil plantations by just one Palm oil company.[xlvii] In 2017 alone, over 155,000 hectares (600 square miles) of Peruvian forests were cut down.[xlviii]

“Illegal deforestation” encompasses a range of unlawful activities, including logging without permits—often on public lands such as Indigenous territories or protected areas—land clearing that exceeds the Forest Code’s limits for agricultural use on private properties and actions associated with grilagem. Grilagem is a term used in Brazil to describe the illegal practice of forging or falsifying land titles to claim ownership of public or private land.[xlix]

The pathways to deforestation are often interconnected. For instance, in areas where land is undesignated and there are weak forest protections, individuals or companies may employ loggers to extract valuable hardwoods like mahogany and ipê (also known as Brazilian walnut or lapacho). Harvesting these trees not only removes keystone species but also causes significant damage to the surrounding ecosystem due to the heavy equipment used for extraction and transport. The profits from selling these high-value woods are frequently reinvested into clearing the remaining forest. Once deforested, the land is typically converted into pasture and populated with cattle, providing a basis to claim the land is in productive use. This facilitates the eventual acquisition of a fraudulent private title—effectively completing the process of grilagem.

Poverty plays a role in deforestation, as some of the most impoverished communities are located near rainforests. To the rural poor, the rainforest becomes a source of survival where few other options exist.[l] Because they lack the resources to improve the existing cleared land, they are forced to move and deforest another piece of land, continuing the destruction cycle. These poor farm households have little incentive to care about the environmental effects of their actions.

Deforestation is affected mainly by the uneven distribution of wealth. Shifting cultivators at the forest frontier are among the poorest and most marginalized sections of the population. They usually own no land and have little capital. Consequently they have no option but to clear the virgin forest. Deforestation including clearing for agricultural activities is often the only option available for the livelihoods of farmers living in forested areas.[li]

A 2022 report by the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information reveals that 232 Indigenous community leaders in the Amazon region were killed over land and natural resource disputes between 2015 and the first half of 2019.[lii] Colombia has the highest number of murders of Indigenous leaders and environmental activists in the region and the world. Ángela Kaxuyana, an Indigenous leader with the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB), highlights the grim connection between environmental destruction and violence: “There is a significant increase in deforestation, and related to this deforestation is the killing of Indigenous leaders defending their territory.” This troubling trend underscores the dangers faced by those on the front lines of protecting the Amazon’s ecosystems and Indigenous lands.

Gold mining has rapidly increased in parts of the Amazon, with small clandestine operations making up more than 50% of all gold mining activities. In the Madre de Dios region of the Peruvian Amazon, from 1999 to 2012, the area of gold mining increased by 400%, and following the 2008 global economic recession, gold mining tripled. From 2008 to 2012, mines expand by deforesting approximately 61 square kilometers (23 square miles) per year in just this area.[liii] The 500 square kilometers (193 square miles) of cleared rainforest is equal to double the size of the city of Boston. Illegal gold mining is rampant and is either simply informal or run by criminal mining organizations, driving other criminal activities such as human trafficking, forced labor, prostitution, and money laundering.[liv] In Peru, illegal mining is an enormous business estimated in 2012 to be worth more financially than the cocaine trade.[lv]

With this Peruvian gold rush, as many as 30,000 miners[lvi] swarmed along the Madre de Dios River, not only clearing forests but using mercury as the easiest, yet highly toxic, way to extract the gold.[lvii] Artisanal, or small-scale, miners release an estimated 1.32 kilograms (2.9 pounds) of mercury into waterways for every 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of gold extracted.[lviii] Worldwide, artisanal gold mining releases 900 metric tons (1,000 tons) of mercury into the environment annually.[lix] This accounts for one-third of all environmental mercury contamination and is the second-worst source of mercury pollution globally after the burning of fossil fuels.[lx] Mercury enters the air when burned off during the gold extraction process or enters waterways, where plants, fish, and humans eventually take it up. The mercury damages the nervous system of miners and their families. It also travels thousands of miles in the atmosphere, settling in oceans and river beds worldwide, and then it biomagnifies up the food chain.

“The continued use of mercury in gold mining threatens millions of people all over the world, since mercury is a global air pollutant,” said Michael Bender, a coordinator for the Zero Mercury Working Group, a coalition of 40 groups worldwide that campaigns to reduce mercury use. “We’re talking about a neurotoxin that science clearly shows threatens pregnant women, their fetus and those who eat large amounts of fish.”[lxi]

In 1965, only one highway existed in the Brazilian Amazon. Now, numerous roads penetrate into the rainforest.[lxii] As of 2012, there were 96,500 kilometers (60,000 miles) of roads in the Amazon Basin,[lxiii] with 51,000 kilometers (over 31,600 miles) built just in Brazil between 2004 and 2007.[lxiv] Oil and gas access roads are also creeping deeper into the western Amazon. Oil and gas blocks now cover 730,000 square kilometers (281,800 square miles), which is larger than the state of Texas.[lxv]

Oil extraction poses a significant threat to the Amazon biome, contributing to deforestation, habitat destruction, and pollution. According to estimates from the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information, oil fields occupy approximately 9.4% of the Amazon's total area, equivalent to 80 million hectares.[lxvi] The environmental consequences of this activity are profound, including contamination of soil and waterways, loss of biodiversity, and disruption of indigenous communities. Ecuador, with “more than half (52%) of the Ecuadorian Amazon an oil field,” is the epicenter of oil extraction in the region and is responsible for a staggering 89% of Amazon's crude oil exports. This concentration of activity underscores the intense pressure placed on Ecuador’s portion of the rainforest, where oil infrastructure and operations carve into one of the world’s most vital ecosystems.

Roads are the primary drivers of deforestation and environmental degradation. They are often built by industries that directly cause deforestation, such as mining, energy exploitation, and commercial logging. Roads also allow access to settlers, land speculators, ranchers, farmers, and illegal miners and loggers. The hot winds that dry out forests along the edges of roadways can result in wildfires and forest degradation that weaken ecosystems.[lxvii] According to Dr. William Laurance of the Centre for Tropical Environmental & Sustainability Science at James Cook University in Australia,

The incredible expansion of roads into the last remaining tropical wildernesses—this is a true environmental crisis, because such roads open up a Pandora’s Box of problems, often leading to large-scale forest destruction and degradation.[lxviii]

Completing more paved roads allowed settlers to make their way north and west into the forest. Most of the Amazon deforestation has occurred along these highways in the southern part of the Amazon basin, known as the “Arc of Deforestation.”

Opening roads inevitably sets in motion a chain of land invasion, land speculation, and deforestation that quickly escapes government control. An urgent example of this is the planned reopening of the abandoned Manaus-Porto Velho highway, which, along with existing and planned roads linking to this highway, would open about half of what is left of Brazil’s Amazon rainforest to the soy growers, ranchers, loggers, and others from the notorious “arc of deforestation” that stretches along the southern edge of the region.[lxix]

End of the Amazon

From 1970 to 2017, nearly 20% of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest was lost, and an additional 6% is considered “highly degraded.”[lxx] By 2016, Brazil’s Amazon forest, initially the size of Western Europe, had been deforested by 784,666 square kilometers (over 300,000 square miles), or the size of France and the United Kingdom combined.[lxxi] The ever-growing deforestation of the Amazon will reach a point that scientists warn will have significant consequences.

As deforestation degrades the forest, there will be decreased rainfall and a longer dry season because fewer trees create moisture in the atmosphere. As its name implies, rainforests require large amounts of rain, and as precipitation decreases at some point, the area will no longer be able to support a rainforest ecosystem.[lxxii] A 2021 study in Nature found the impacts of deforestation policy scenarios on the region’s agriculture on the Amazon.[lxxiii]

Widespread deforestation results in a negative-sum hydrological and economic game because lower rainfall and agricultural productivity at larger scales outdo local gains. Under a weak governance scenario, SBA [Southern Brazilian Amazon] may lose 56% of its forests by 2050. Reducing deforestation prevents agricultural losses in SBA up to US$ 1 billion annually.

The end result of deforestation is that more than 50% of the rainforest can be radically transformed into degraded savanna, where the vegetation is made up of more coarse grasses and scattered tree growth.[lxxiv] In addition to direct deforestation, other factors impact the rainforest. A warming climate and utilizing fire to clear areas of felled trees and weedy vegetation for pasture or agricultural crops also affect the forest’s hydrological [water] cycle.[lxxv] Together, these forces are bringing the Amazon to a tipping point. In 2010, the World Bank released a report detailing Amazon’s dire situation and how it is close to this point of no return. Thomas Lovejoy, head of the committee responsible for this significant scientific investigation and world-renowned tropical biologist, warned,

The World Bank released a study that finally put the impacts of climate change, deforestation and fires together. The tipping point for the Amazon is 20 percent deforestation, and that is a scary result. The Amazon jungle is very close to a tipping point, and if destruction continues, it could shrink to one-third of its original size in just 65 years. The forest eventually converts to cerrado (the Brazilian savanna) after a lot of fire, human misery, loss of biodiversity and emission of carbon into the atmosphere.[lxxvi]

The Amazonian south and southeast will receive much less rainfall making those areas more prone to fires. This will destroy the forest and further dry out the surrounding forest, reducing the Amazon’s ability to produce rain. Clearing leads to more drought, leading to more fires and fewer trees, resulting in decreased rainfall and further drought. Extreme droughts have become more frequent and intense.[lxxvii] Once the tipping point is reached, it triggers a self-amplifying forest loss that pushes the Amazon into an irreversible downward slide. The World Bank report concluded,

For the Amazon as a whole, the remaining tropical forest will shrink to about three-quarters of its original area by 2025 and further to about only one-third of its original extension by 2075 as a result of these combined impacts of climate change, deforestation, and fire.[lxxviii]

In 2018, Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, a Brazilian Academy of Sciences member, stated that once 20-25% of the Amazon is deforested, the Amazon could “flip” to a non-forest ecosystem in eastern, southern, and central Amazonia.[lxxix] He warns that deforestation will be disastrous if it continues at current levels. The Amazon region could become drier and drier, unable to support healthy habitats or crops. Nobre stated,

Although we don’t know the exact tipping point, we estimate that the Amazon is very close to this irreversible limit. Deforestation of the Amazon has already reached 20 percent, equivalent to 1 million square kilometers [386,000 square miles].[lxxx]

In 2019, Nobre declared that Amazon had reached a critical tipping point and urged immediate and drastic action to stave off the global disaster of its collapse.

We are no longer in a situation where the tipping point is on the horizon. It is here and now. If allowed to tip, it will affect continental climate and produce dieback in the south and east part of the central Amazon. That would represent an unconscionable release of carbon, loss of biodiversity and impact on the local people.[lxxxi]

A 2024 study published in Nature warns that by 2050, between 10% and 47% of the Amazon rainforest could face “compounding disturbances” that “may trigger unexpected ecosystem transitions.”[lxxxii] This scenario raises the alarming possibility of vast areas of vibrant rainforest transforming into dry savannah. The researchers' analysis suggests that these combined pressures could drive the Amazon toward a large-scale tipping point within the next few decades.

Dr. Bernardo Flores, lead author and researcher at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil, reflects on the findings:

“It is surprising how the combination of stressors and disturbances are already affecting parts of the central Amazon… [which] can already transition into different ecosystems. Then, when you put everything together, the possibility that by 2050 we could cross this tipping point, a large-scale tipping point, is very scary and I didn’t really think it could be so soon.”[lxxxiii]

The Mato Grosso region in the southern Amazon, an area more than twice the size of California, is the most damaged region of the Amazon rainforest, which has already had 17% of its forest cleared. Mônica Carneiro Alves Senna and colleagues at the Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil, used computer models to simulate how the area would recover from various deforestation amounts. When 20% of the area was deforested, they found that the region became a dry, bare savanna and could not recover to its forested state even after 50 years.[lxxxiv] Patrick Keys of the Stockholm Resilience Center in Sweden warns that Brazil’s megacities of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, as well as Argentina’s Buenos Aires, could also be vulnerable because much of their rainfall originates in the Mato Grosso region, where forests and grasslands are rapidly being replaced by corn and soy fields.[lxxxv]

What would be even more devastating is that if the forest itself is drawing in moisture across South America from the Atlantic, as proposed by the “biotic pump” theory, then as it becomes more and more deforested, the force that drives moisture across the continent will significantly diminish. This would create a situation that could turn the area not into a savanna but into a much drier desert.

…were the forest to disappear, then according to the [biotic pump] theory, moisture would no longer be sucked in and, given the natural fall-out rate of rainfall, some 600 kilometres [370 miles] from evaporation to precipitation, the land would dry out and in all likelihood turn to desert. Were that the case it would be a disaster of momentous proportions, not just dwarfing the likely changes resulting from global warming but indeed compounding them.[lxxxvi]

In the Colombian Amazon, Leticia is about 2,500 kilometers (1,500 miles) west of the Brazilian coast and is currently a rainforest that receives 2,500 millimeters (98 inches) a year. If the moisture transportation system collapses, it could be altered to be as dry as Israel’s Negev Desert, which only gets 10 centimeters (4 inches) of rain yearly.[lxxxvii]

The tremendous amount of moisture pumped into the atmosphere by the billions of trees in the Amazon plays a significant role in regulating the earth’s climate. If disrupted, the climate throughout the region and beyond will be significantly impacted.

The importance of the Amazon rainforest in regulating not only South America’s climate but also that of the entire world cannot be overestimated. Like the Earth’s cryosphere, the Amazon and other rainforests are essential geographic features of the planet that help regulate the climate and provide habitat for unique wildlife. As with the melting polar regions, the loss of the Amazon to capitalist “resource development” will prove to be a self-destructive act for all of mankind.[lxxxviii]

In 2015, much of Brazil was gripped by one of the worst droughts in its history. Massive reservoirs were dry, and water was rationed in São Paulo, a megacity of 20 million people, Rio, and many other places.[lxxxix] In October 2014, which is usually the beginning of the rainy season, it was drier than any time since 1930, leaving the volume of the water reserve system that supplies the state of São Paulo, Brazil, down to 5% of capacity.[xc]

A Princeton study suggested that deforesting the Amazon could potentially contribute to drought in places as far away as California.[xci] Other research indicates that recent droughts from Mexico to Texas have been linked to tree-cutting in the Amazon. Specifically, deforestation of the Amazon was found to severely reduce rainfall in the Gulf of Mexico, Texas, and northern Mexico during the spring and summer seasons when water is crucial for agricultural productivity.

Associated changes in air pressure distribution shift the typical global circulation patterns, sending storm systems off their typical paths. And, because of the Amazon’s location, any sort of weather hiccup from the area could signal serious changes for the rest of the world like droughts and severe storms.[xcii]

Each year, the eight trillion tons of water evaporating from Amazon forests[xciii] produce rainfall in the Andes Mountains in the west and agricultural areas in southern Brazil, Paraguay, and northern Argentina. Moisture from the Amazon reaches all the way up to the Midwestern United States when farmers are planting. Losing the Amazon rainforest could diminish rainfall across the Americas, with potentially severe consequences for farmers. Adrian Forsyth, a tropical ecologist who is the president and co-founder of the Amazon Conservation Association, noted,

There’s this trillion-dollar subsidy of rainfall coming to agricultural and urban areas that people simply didn’t know about until recently.[xciv]

For decades, economic and political forces have been steadily gnawing away at the Amazon, pushing it ever closer to tipping into an unstoppable downward spiral. Permissive land-use policies and cheap farm acreage have helped catapult Brazil into an agricultural superpower. Brazil is the world’s largest soy, beef, and chicken exporter and a major pork and corn producer.[xcv] More international markets for Brazilian beef have opened, with exports steadily increasing.[xcvi]

Agriculture is not only impacting the Amazon rainforest. Roughly the size of Mexico, the largest savanna in South America, the cerrado, is rapidly being converted to mega-farms to grow products such as soy to feed livestock and sugarcane to make biofuels. From 2008 to 2018, this habitat lost 105,000 square kilometers (40,541 square miles), or about the size of South Korea.[xcvii] The cerrado has seen about 50% of its native forests and grasslands converted to farms, pastures, and urban areas over the past 50 years. Every year, some 51,800 square kilometers (20,000 square miles), an area the size of New Jersey, is cleared to make room for crops such as soy, wheat, and cotton.

Propelled by the worldwide growing desire for biofuels, meat, chicken, and pork, large portions of South America’s natural environment are being remade into massive mega-farms to feed these human appetites. Brazil’s large-scale agribusiness is plowing under the cerrado and could disappear entirely by 2030[xcviii], destroying 11,000 plant species, 199 species of mammals, and 837 species of birds. Deforestation in the cerrado is also changing Brazil’s water cycle, further raising the likelihood of drought in the coming decades.

The fruits of converting the cerrado are fed into the maw of the global commodity market — soybeans to feed livestock in China, sugar cane to make ethanol to meet U.S. biofuel mandates, beef to feed the world’s growing middle classes. The market — animated by our desires — moves so much faster than our learning curve. Our loyalties are to our own interests. Our affections rarely extend to scrubby woodlands and carnivorous plants. Our convictions don’t run that deep underground.[xcix]

There is an ever-increasing demand for Brazil’s agricultural commodities worldwide and a push for large-scale transportation and energy infrastructure projects, including Amazon dams, roads, and railways.[c] Furthermore, despite cities like São Paulo already experiencing drought due to deforestation, the clear-cutting is likely to continue. Richard George, forest campaigner for Greenpeace U.K., explains,

Ironically, the drought is already affecting Brazil’s agribusiness sector, a major cause of forest destruction in the Amazon. The risk, of course, is that instead of putting pressure on the government to stop deforestation, Brazil’s powerful agribusiness lobby will demand the right to clear even more forest to make up for the declining yields.[ci]

Dr. Nobre and other climate experts are urging an immediate halt to deforestation, as well as large-scale planting of new forests, to bring the Amazon back to full health and stabilize its pivotal role in climate.[cii] Yet, the upturn in resource conversion and degradation of the Amazon’s natural habitat will likely gain further momentum. Moreover, with political and economic pressures, existing environmental protections are in danger of being rolled back, quickening deforestation. With the 2018 Brazilian election of Jair Bolsonaro as president, one group estimates a rapid increase in deforestation in the coming years. In addition, in 2019, the Brazilian government, under the leadership of Bolsonaro, unveiled plans to privatize the Trans-Amazonian Highway to complete and fully pave this 4,000-kilometer (2,485-mile) long road, which has already caused extensive deforestation.[ciii]

Based on an economic modeling approach that simulates the competition for land in order to meet a growing global demand for major commodities such as beef and soybeans, we estimate that, if environmental protections are removed by Brazil’s next president, the average annual loss of primary forest in the Amazon will quickly rise to 25,600 square kilometers (9,884 square miles) per year, a figure similar to the deforestation rates measured at the beginning of the 2000s and an increase of 268 percent from 2017.[civ]

Deforestation in Amazônia has seen significant fluctuations over the years. After peaking at 27,772 square kilometers in 2004, deforestation was dramatically reduced by 84%, reaching a low of 4,471 square kilometers in 2012. Although not as high as predicted, by 2021, the deforested area climbed to 13,235 square kilometers—equivalent to 1.8 million soccer fields.[cv]

Deforestation and fires in the Amazon have soared under the administration of Brazil’s current president, Jair Bolsonaro, who has adopted policies that undermine Brazil’s various environmental protection and monitoring agencies. Under Bolsonaro, the Brazilian Amazon has lost an area of forest larger than Belgium and recorded its highest deforestation rate in 15 years.[cvi]

With this estimated acceleration in deforestation by 2021, the tipping point of 20% is quickly crossed, and by 2029, it will exceed 25%, sending the Amazon into an unstoppable tailspin. Unfortunately, the situation could be even worse. A combination of expanding global demands for Amazonian products, Amazon forest fires, and drought may drive a more rapid dieback. By 2030, half the Amazon could be cleared or damaged, releasing 15 to 26 billion metric tons (16.5 to 28.6 billion tons) of carbon into the atmosphere.

Rising worldwide demands for biofuel and meat are creating powerful new incentives for agro-industrial expansion into Amazon forest regions. Forest fires, drought and logging increase susceptibility to further burning while deforestation and smoke can inhibit rainfall, exacerbating fire risk. If sea surface temperature anomalies (such as El Niño episodes) and associated Amazon droughts of the last decade continue into the future, approximately 55% of the forests of the Amazon will be cleared, logged, damaged by drought or burned over the next 20 years, emitting 15–26 Pg [1 petagram = 1 billion metric tons] of carbon to the atmosphere.[cvii]

Forests absorb and store CO2 from the atmosphere. That CO2 is released back into the atmosphere when trees are cut and burned. The Amazon rainforest absorbs one-fourth of the CO2 absorbed by all the land on Earth and is known as a carbon sink. However, because of deforestation, the amount absorbed today is 30% less than in the 1990s.[cviii] As the forest deteriorates and spirals down, a tremendous amount of stored carbon will be released into the atmosphere. So, the forest would flip from a carbon sink to a carbon source, amplifying the effects of a warming climate. Daniel Nepstad, executive director of the Earth Innovation Institute, noted,

There’s this 90 billion-ton pool of carbon leaking out slowly with deforestation, and the potential for large belches of CO2 going into the atmosphere through forest fire is very, very real. It’s actually happening; it’s not a hypothetical thing. Whether or not that locks us into a brand new climate in the Amazon [with half of the region dominated by grasslands instead of forest] remains to be seen, but it’s a potential. [cix]

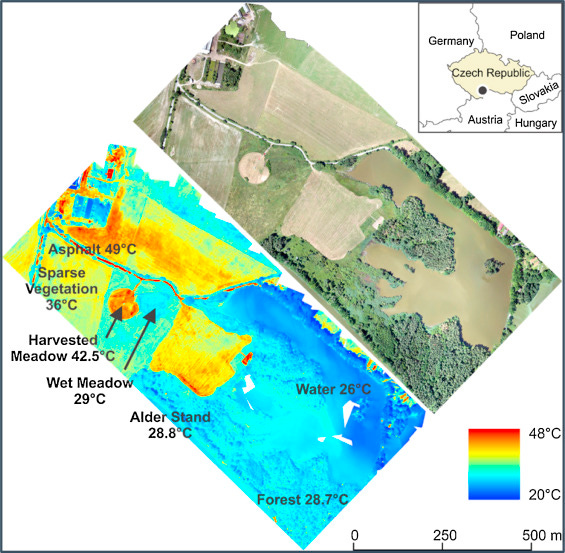

Tropical forests in the crosshairs

Tropical forests cover about 7% of the Earth’s land surface yet produce 40% of its oxygen and are home to about half of all species on Earth.[cx] Forests help moderate local climates, keeping them cool. This effect is partly due to shading and the trees releasing moisture into the air through their leaves. This process extracts energy from the surrounding air, which cools it. This evaporation of hundreds of liters of water daily from a tree’s leaves results in the forests’ climate-cooling effects. Every 100 liters of water equals 70kWh [kilowatt hours] of cooling power or enough to power two 1,440-watt air-conditioning units daily.[cxi]

Deforestation occurs not only in the Amazon but in tropical forests worldwide. Africa and Asia have lost about 55% and 35% of their tropical forests, respectively.[cxii] An estimated 130,000 square kilometers (over 50,000 square miles) of tropical forests are demolished annually.[cxiii] The deforestation rate accelerated from 1980 to 1990 when it was 92,000 square kilometers (over 35,500 square miles) per year.[cxiv] Approximately one-sixth of global carbon emissions are due to cleared or degraded forests.[cxv]

In 2017, slash-and-burn deforestation was primarily responsible for destroying an area the size of Italy. This was the second-worst year for tree loss since records began to be kept in 2001. A total of 292,000 square kilometers (113,000 square miles) were cleared from the Amazon, Congo, Indonesia, and Malaysia.[cxvi] Over 10 years, the planet has lost 945,345 square kilometers (370,000 square miles) of natural forests, or a little over the total size of Venezuela. The forest cover loss rate has doubled since 2003, and deforestation in tropical rainforests has doubled since 2008.[cxvii] Frances Seymour of the World Resources Institute (WRI) said,

Tropical forests were lost at a rate equivalent to 40 football fields per minute. Vast areas continue to be cleared for soy, beef, palm oil and other globally traded commodities. Much of this clearing is illegal. We are trying to put out a house fire with a teaspoon.[cxviii]

In Indonesia and Malaysia, deforestation has been mainly due to substantial global demand for palm oil. The Indonesian Island of Sumatra has been losing forests to palm oil cultivation faster than almost anywhere else on the planet.[cxix]

Off the coast of East Africa, the island country of Madagascar has the third-highest rate of biodiversity on Earth, after Brazil and Indonesia. Since humans’ arrival 2,000 years ago, Madagascar has lost more than 90% of its original forest. Almost 40% of forest cover disappeared from the 1950s to 2000.[cxx] The Makira Forest, located in the northeast part of Madagascar, is one of the largest remaining contiguous tropical rainforest areas in Madagascar. Less than 10% of the Makira Forest remains. The causes of the destruction of Madagascar’s forests are agriculture, uncontrolled wildfires, and lands burned for grazing.

Forests that once blanketed the eastern third of the island were degraded and fragmented, while endemic spiny forests have been diminished by subsistence agriculture, cattle grazing, and charcoal production. The central highlands have mostly been cleared for pasture, rice paddies, and eucalyptus and pine plantations. Each year as much as a third of the country burns, the result of fires set by farmers and cattle herders clearing land for subsistence agriculture. Meanwhile industrial miners from developed countries are tearing away at some of Madagascar’s last remaining forest tracts.[cxxi]

Rosewood logging has affected tens of thousands of acres of protected rainforest. Much of the wood shipped to China to make wood products was eventually sold in Europe and the United States. Illegal sapphire mines have also caused deforestation across Madagascar. Tens of thousands of Madagascans uproot trees and divert streams to find these gemstones, helping them to survive in a country where 70% live in poverty.[cxxii]

Deforestation is likely to reduce rainfall in many parts of the world while increasing it in others, considerably pushing up the global mean temperature. A case study of the effect of deforestation can be found in the Mau Forest in western Kenya, which is part of East Africa. It was once called the “water tower” because it stored rain during the wet seasons and pumped it out to the Rift Valley and Lake Victoria during dry months. From 1998 to 2013, approximately 200,000 hectares (770 square miles or larger than the size of the Hawaiian island of Maui) of the forest were converted to agricultural land.[cxxiii] Conversion of forest land into farms and settlements, illegal logging, and charcoal burning contribute to the destruction,[cxxiv] with 12,600 hectares (48 square miles) of forest lost every year.[cxxv] Only 2% of the country is now forested when, at one time, half of the country was covered with jungles. From 1990 to 2010, East Africa’s Forest shrank by over 20%, from 107 million hectares down to 85 million hectares. That is a loss of 22 million hectares (84,900 square miles) or roughly the size of Utah.[cxxvi]

Now, the region suffers from severe drought and temperature extremes, and the formerly productive land has gone barren. The forest is the source of 11 main rivers feeding into five major lakes, including Lake Victoria, the source of the Nile.[cxxvii] As the rivers that flow from the forest are drying up, Kenya’s harvest, tea industry, cattle ranching, hydroelectricity, lakes, and famous wildlife parks have suffered.[cxxviii] The deforestation at the heart of Kenya has triggered a “cascade of drought and despair in the surrounding valleys.” In 2009, the normal rains failed. The breadbasket of Kenya, Narok County, became a barren dustbowl in April, the year’s wettest month. Millions of cattle died, and the government declared a national emergency, with millions of Kenyans facing starvation.

In the Mau Forest, land surface temperatures measure 19°C (66°F), whereas in the agricultural land, which until recently had been forest, they hover close to 50°C (122°F). Kenya Sarah Higgins, a conservationist who runs the Little Owl Sanctuary for injured birds near Lake Naivasha east of the Mau Forest, has seen clear indications that the weather has changed with the forest’s destruction.

When she started farming 30 years ago “we were almost guaranteed sufficient rainfall for our crops.” Then came the destruction of the Mau Forest, and the area above and on either side of the farm was “denuded of trees and overgrazed, down to bare Earth. Our regular rainfall started to fail and we were seeing dry years, poor yields and more droughts.”[cxxix]

In February 2017, the Kenyan government declared a national drought emergency. Severe drought had dried up water resources in half of Kenya’s 47 counties, and an estimated 3 million people lacked access to clean water.[cxxx] UNICEF reported in 2017 that 3.4 million people faced starvation in the country following a drought that ravaged the country that year.[cxxxi] Oxfam stated that the 2017 drought was “worse in a number of ways than in 2011, with some areas experiencing the failure of three rains in a row.”

Thousands of herders fled their traditional grazing lands, searching for water and pasture as a biting drought engulfed East Africa, and their animals have swept through farms and conservation areas.[cxxxii] Dozens have been killed and injured in Kenya’s drought-stricken Laikipia region as armed herders searching for scarce grazing land drove tens of thousands of cattle onto private farms and ranches from poor-quality common land.[cxxxiii] Increased droughts due to deforestation exacerbated by climate change and population growth are increasing stress and conflicts throughout the area. More disasters loom on the horizon as deforestation of the Mau Forest continues.

As in the Mau Forest case, the loss of tropical forests worldwide will significantly impact the climate. Michael Wolosin and Nancy Harris of the World Resources Institute published a study that noted the global impact of tropical forest deforestation.

Tropical forest loss is having a larger impact on the climate than has been commonly understood. Deforestation contributes to warming and disrupts rainfall patterns at multiple scales. These changes will impact all of us, threatening agricultural productivity in the tropics and beyond... changes in rainfall driven by tropical deforestation combined with warmer temperatures could pose a substantial risk to agriculture in key breadbaskets halfway around the world in parts of the U.S., India, and China.[cxxxiv]

Altering land use to agriculture or pastures by destroying forests significantly impacts the climate’s warming. This human activity accounts for a rise in CO2 and increases in methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), which are also greenhouse gases. These factors could account for as much as 40% of the warming in the climate since 1850.[cxxxv] This makes deforestation a critical component of the Paris Climate Agreement to keep the global temperature from rising less than 1.5°C (2.7°F) or, at worst, 2°C (3.6°F). The authors of a 2017 study noted that if land conversion changes continued unabated, temperatures would increase significantly even if all other human-caused climate-related activities, such as fossil fuel burning, were halted entirely. Temperatures could even exceed the upper agreed limit of 2°C (3.6°F).

Using a more realistic estimate of tropical-business-as-usual conversion of forests, we estimate about 1°C rise in temperature will result by 2100 solely due to LULCC (land use and land cover change), with a substantial probability of exceeding 2°C warming relative to preindustrial temperatures even without non-LULCC (e.g., burning of fossil fuels) emissions.

The Amazon rainforest is still the world's largest, pristine, and roadless wilderness. Yet, an increasing number of people in the Amazon region have more investment money pouring in for economic development every year. The virtually singular drive for profit-generating growth fuels the ever-expanding road system that increases legal and illegal enterprises of ranching, agriculture, logging, mining, and more at the expense of the long-term viability of the rainforest.

Hacking down our future

The ongoing destruction of this ever-dwindling jungle is occurring just as it has happened throughout modern human history. Once people find resources they value, they lay waste to the environment to acquire them. Short-term profits and their political power almost always trump long-term thinking and sustainability. Deforestation destroys the habitat for an immense diversity of species and threatens the welfare of more than a billion people who rely on forests for their livelihoods. Large-scale deforestation is a global catastrophe in the making. It is primarily driven by the rampant consumer desires in developed countries for commodities such as beef, soy, gold, timber, and palm oil. Harrison Ngau, an Indigenous tribesman from Sarawak, Malaysia, explains,

The roots of the problem of deforestation and waste of resources are located in the industrialized countries where most of our resources such as tropical timber end up. The rich nations with one-quarter of the world’s population consume four fifth of the world’s resources. It is the throw away culture of the industrialized countries now advertised in and forced on to the Third World countries that is leading to the throwing away of the world. Such so-called progress leads to destruction and despair.[cxxxvi]

Human societies are often dysfunctional and destructive, believing that nature is simply a limitless resource to be consumed. Clearing forests may make profits for those doing it, but it impoverishes and imperils the planet as a whole over the long run. Reducing deforestation and replanting forests need to be prioritized in the Amazon and forests across the globe. The WWF's (World Wide Fund for Nature) 2015 Living Forests report identified 11 major global deforestation hotspots.[cxxxvii] These are places where the most extensive forest loss concentrations or severe degradation are projected to occur between 2010 and 2030 under business-as-usual scenarios and without interventions to prevent losses. According to Alfonso Cauteruccio, president of Greenaccord,

The forests represent the balance and stability within the ecosystem. However, each year we lose 16 million hectares [160,000 square kilometers/62,000 square miles] of forest. These are astonishing figures and they should be enough to start immediate action since forests produce oxygen, filter air, regulate the humility of the surrounding area, absorb enormous quantities of greenhouse gas and provide refuge and sustenance to local populations. Forests should be considered universal resources because they guarantee the equilibrium of the planet and because their protection means the protection of all humanity, but instead, they depend on the weak legislation of every country.[cxxxviii]

If the governments and people of the world do not get serious about bringing the forces of destructive development under control, these magnificent rainforests will continue to disappear decade by decade. Not only do forests need to be conserved and restored, but so do other vital natural ecosystems, including mangroves and peatlands. Without a serious effort to solve this ecosystem destruction problem, the planet will lose its most valuable climate-stabilizing resources, vastly increasing the risk of a warming climate.

Reforestation removes CO2 from the atmosphere and thus cools the climate. Clearing tropical forests and draining peatlands for agriculture, ranching, logging, mining, and increased settlements transfers CO2 from these ecosystems to the atmosphere and heats the climate. In addition, the use of fire, often used in the tropics to quickly clear forest land, rapidly releases CO2, CH4, and N2O into the atmosphere, increasing the warming further.

The globalization of deforestation is far outpacing public understanding of the consequences of the resulting blowback. The Amazon, massive enough to influence global weather systems, may already be nearing an irreversible tipping point. If this vital rainforest collapses into a savanna or desert, the cascading effects on biodiversity, climate, and human civilization will be catastrophic.

No one can fully foresee the cascading impacts as it collapses into a savanna or desert. Yet, humankind proceeds on a reckless course forward toward impending devastation. Destroying the world’s rainforests endangers our civilizations, for it is those very ecosystems that provide climate stability that enable them to flourish. By the time most of the public acts - it may be too late, with disastrous results for biodiversity, climate, and all life on the planet.

What you can do!

Tropical forests are being destroyed at an alarming rate. If current deforestation rates continue, all of our planet’s original rainforest could be lost within decades, resulting in massive extinctions, accelerated climate change, and increased desertification. Here are some simple steps that you can take at a personal level to make a difference.

Avoid foods that cause deforestation—Many of the foods we eat are grown on deforested lands. For example, beef, soybean, and palm oil are principal drivers of deforestation in the Amazon basin. Fortunately, we can limit our contribution to these destructive industries. Reduce your meat intake, and buy your meat from local farms that use sustainable practices. Check your food product labels for soy or palm oil ingredients, and buy alternatives when possible. Choosing sustainably produced foods and products forces companies to change their practices.

Avoid products that cause deforestation. Choose products that are responsibly sourced or made from recycled materials. Mining for gold, mining for sapphires, and logging-threatened trees like ebony, mahogany, and rosewood all drive rainforest destruction—research before you buy.

Buy sustainable wood products—Go paperless or reduce your use of paper products. Purchase paper products from sustainable sources, such as recycled paper or cardboard, tissues, paper towel, and napkins. Purchase eco-friendly office supplies, school and craft supplies, etc.

Choose used furniture—Consider purchasing or repurposing used furniture you already own and refurbishing it when needed. Even if the piece requires some work, such as a new coat of paint or needing to be upholstered, you can create a piece that is uniquely yours while saving money.

Use fewer paper products. Support companies committed to reducing deforestation and harvesting wood from sustainably sourced forests. This ensures that any damage to the surrounding ecosystem can be monitored and managed.

Plant Trees—Plant native trees, where possible, near your home or in your community. Join organizations that are committed to stopping tropical deforestation and are engaged in replanting trees.

[i] Daniel C. Nepstad, “Interactions among Amazon land use, forests and climate: prospects for a near-term forest tipping point,” Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B, February 2008, pp. 1737–1746, doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.0036

[ii] Alexis Lassman, “New Theory on How the Amazon Controls the Earth’s Climate,” Uplift, March 17, 2017, https://upliftconnect.com/amazon-controls-earths-climate

[iii] Daniel Glick, “Can the Amazon Save the Planet? Scientists climb to perilous heights to gauge how much carbon dioxide the rainforest is absorbing,” Scientific American, April 3, 2017, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-the-amazon-save-the-planet

[iv] Amanda Paulson, “Camp Amazon: Inside the ‘lungs of the Earth’,” Christian Science Monitor, September 24, 2018, https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/2018/0924/Camp-Amazon-Inside-the-lungs-of-the-Earth

[v] Daniel Glick, “Can the Amazon Save the Planet? Scientists climb to perilous heights to gauge how much carbon dioxide the rainforest is absorbing,” Scientific American, April 3, 2017, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-the-amazon-save-the-planet

[vi] Rodrigo Hierro, et al., “The Amazon basin as a moisture source for an Atlantic Walker-type Circulation,” Atmospheric Research, October 2018, DOI: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2018.10.009

[vii] “Inside the Amazon,” WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature, http://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/amazon/about_the_amazon

[viii] Stephen Leahy, “The REAL Amazon-gate: On the Brink of Collapse Reveals Million $ Study,” February 104 2010, https://stephenleahy.net/2010/02/15/the-real-amazon-gate-on-the-brink-of-collapse-million-study

[ix] Daniel Glick, “Can the Amazon Save the Planet? Scientists climb to perilous heights to gauge how much carbon dioxide the rainforest is absorbing,” Scientific American, April 3, 2017, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/can-the-amazon-save-the-planet

[x] Amanda Paulson, “Camp Amazon: Inside the ‘lungs of the Earth’,” Christian Science Monitor, September 24, 2018, https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/2018/0924/Camp-Amazon-Inside-the-lungs-of-the-Earth

[xi] Doug Bennett, “What Are the Reactants & Products in the Equation for Photosynthesis?” Sciencing, April 30, 2018, https://sciencing.com/reactants-products-equation-photosynthesis-8460990.html

[xii] “Amazon rainforest is home to 16,000 tree species, estimate suggest,” The Guardian, October 18, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/oct/18/amazon-rainforest-tree-species-estimate

[xiii] David Wallace-Wells, “Could One Man Single-Handedly Ruin the Planet?” Intelligencer, October 31, 2018, http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/10/bolsanaros-amazon-deforestation-accelerates-climate-change.html

[xiv] Oliver L. Phillips, and Roel J. W. Brienen, “Carbon uptake by mature Amazon forests has mitigated Amazon nations’ carbon emissions” Carbon Balance Manage, February 15, 20178, DOI 10.1186/s13021-016-0069-2

[xv] “Climate Change and Tropical Forests,” Global Forest Atlas, https://globalforestatlas.yale.edu/climate-change/climate-change-and-tropical-forests

[xvi] Trends in Global CO2 Emissions 2016 Report, PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, The Hague, 2016, p. 43.

[xvii] Rhett Butler, “Rainforest Ecology,” Mongabay, January 26, 2017, https://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/rainforest_ecology.html

[xviii] Alexis Lassman, “New Theory on How the Amazon Controls the Earth’s Climate,” Uplift, March 17, 2017, https://upliftconnect.com/amazon-controls-earths-climate

[xix] Airbus A380 Specs, http://www.modernairliners.com/airbus-a380/airbus-a380-specs

[xx] “Trees in the Amazon Generate Their Own Clouds and Rain, Study Finds,” Yale Environment 360, August 7, 2017, https://e360.yale.edu/digest/trees-in-the-amazon-generate-their-own-clouds-and-rain-study-finds

[xxi] Niklas Boers, et al., “A deforestation-induced tipping point for the South American monsoon system,” Scientific Reports, January 25, 2017, DOI: 10.1038/srep41489

[xxii] Alexis Lassman, “New Theory on How the Amazon Controls the Earth’s Climate,” Uplift, March 17, 2017, https://upliftconnect.com/amazon-controls-earths-climate

[xxiii] Peter Bunyard, “Without its rainforest, the Amazon will turn to desert,” Ecologist, March 2, 2015, https://theecologist.org/2015/mar/02/without-its-rainforest-amazon-will-turn-desert

[xxiv] Fred Pearce, “Rainforests may pump winds worldwide,” New Scientist, April 1, 2009

[xxv] Fred Pearce, “Rivers in the Sky: How Deforestation Is Affecting Global Water Cycles,” Yale Environment 360, July 24, 2018, https://e360.yale.edu/features/how-deforestation-affecting-global-water-cycles-climate-change

[xxvi] Grennan Milliken, “Over Half Of All Amazonian Tree Species Are In Danger,” Popular Science, November 20, 2015, https://www.popsci.com/over-half-all-amazonian-tree-species-are-globally-threatened

[xxvii] “Rain Forests,” National Geographic, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rain-forests

[xxviii] Aline C. Soterroni, Fernando M. Ramos and Michael Obersteiner, “Fate of the Amazon is on the ballot in Brazil’s presidential election (commentary),” Mongabay, October 17, 2018, https://news.mongabay.com/2018/10/fate-of-the-amazon-is-on-the-ballot-in-brazils-presidential-election-commentary

[xxix] Camila Domonoske, “Deforestation Of The Amazon Up 29 Percent From Last Year, Study Finds,” NPR, November 30, 2016, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/11/30/503867628/deforestation-of-the-amazon-up-29-percent-from-last-year-study-finds

[xxx] “For cattle farmers in the Brazilian Amazon, money can’t buy happiness,” The Conversation, October 24, 2017, https://theconversation.com/for-cattle-farmers-in-the-brazilian-amazon-money-cant-buy-happiness-85349

[xxxi] Nathalie Walker, Barbara Bramble and Sabrina Patel, “From Major Driver of Deforestation and Greenhouse Gas Emissions to Forest Guardians? New Developments in Brazil’s Amazon Cattle Industry,” National Wildlife Federation, December 2010

[xxxii] Julie Kerr Casper, PhD, Forests - More than Trees, 2007, Chelsea House, p. 74.

[xxxiii] “Amazonian challenges: Cattle ranching and agriculture,” Open Learn, May 27, 2014, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/nature-environment/amazonian-challenges-cattle-ranching-and-agriculture

[xxxiv] “Soybeans,” Union of Concerned Scientists, https://www.ucsusa.org/global-warming/stop-deforestation/drivers-of-deforestation-2016-soybeans

[xxxv] Rebecca Simmon, “Tropical Deforestation,” NASA Earth Observatory, March 30, 2007, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/Deforestation/deforestation_update.php

[xxxvi] Liz Kimbrough, “How close is the Amazon tipping point? Forest loss in the east changes the equation,” Mongabay, September 20, 2022, https://news.mongabay.com/2022/09/how-close-is-the-amazon-tipping-point-forest-loss-in-the-east-changes-the-equation

[xxxvii] S. K. Chakravarty, et al. Deforestation: Causes, Effects and Control Strategies, DOI: 10.5772/33342

[xxxviii] “Amazonian challenges: Cattle ranching and agriculture,” Open Learn, May 27, 2014, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/nature-environment/amazonian-challenges-cattle-ranching-and-agriculture

[xxxix] “Amazonian challenges: Cattle ranching and agriculture,” Open Learn, May 27, 2014, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/nature-environment/amazonian-challenges-cattle-ranching-and-agriculture

[xl] Elizabeth Palermo, “More Than 30,000 Miles of Roads Built in Amazon in 3 Years,” Live Science, November 4, 2013, https://www.livescience.com/40914-amazon-road-building.html

[xli] Ian Johnston, “Amazon jungle faces death spiral of drought and deforestation, warn scientists,” Independent, March 13, 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/amazon-rainforest-drought-deforestation-jungle-death-spiral-potsdam-institute-a7627931.html

[xlii] David Adam, “Amazon rainforests pay the price as demand for beef soars,” The Guardian, May 31, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/may/31/cattle-trade-brazil-greenpeace-amazon-deforestation

[xliii] Ana Mano, “China-driven Brazil beef bonanza seen lasting: Abiec,” Reuters, December 11, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-beef-abiec/china-driven-brazil-beef-bonanza-seen-lasting-abiec-idUSKBN1OA1Z8

[xliv] David Adam, “Amazon rainforests pay the price as demand for beef soars,” The Guardian, May 31, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/may/31/cattle-trade-brazil-greenpeace-amazon-deforestation

[xlv] “Amazonian challenges: Cattle ranching and agriculture,” Open Learn, May 27, 2014, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/nature-environment/amazonian-challenges-cattle-ranching-and-agriculture

[xlvi] David Adam, “Amazon rainforests pay the price as demand for beef soars,” The Guardian, May 31, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/may/31/cattle-trade-brazil-greenpeace-amazon-deforestation

[xlvii] Rhett Butler, “Palm oil company destroys 7,000 ha of Amazon rainforest in Peru,” Mongabay, March 4, 2013, https://news.mongabay.com/2013/03/palm-oil-company-destroys-7000-ha-of-amazon-rainforest-in-peru

[xlviii] James Bargent, “Satellite Images Show Threat of Criminal Activities in Peru’s Amazon,” InSight Crime, March 20, 2019, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/brief/satellite-images-highlight-threat-to-perus-amazon-forest

[xlix] A Balancing Act for Brazil’s Amazonian States An Economic Memorandum, World Bank Group, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/brazil/publication/brazil-a-balancing-act-for-amazonian-states-report, p. 26.

[l] Rhett Butler, “Population, Poverty, and Deforestation,” Mongabay, July 11, 2012, https://rainforests.mongabay.com/0816.htm

[li] S. K. Chakravarty, et al. Deforestation: Causes, Effects and Control Strategies, DOI: 10.5772/33342

[lii] Yvette Sierra Praeli, “The Amazon will reach tipping point if current trend of deforestation continues,” Mongabay, October 3, 2022, https://news.mongabay.com/2022/10/the-amazon-will-reach-tipping-point-if-current-trend-of-deforestation-continues

[liii] Gregory P. Asnera, et al., “Elevated rates of gold mining in the Amazon revealed through high-resolution monitoring,” PNAS, November 12, 2013, vol. 110, no. 46, pp. 18454–18459, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1318271110

[liv] Camilo Carranza, “Peru Running Out of Ideas to Stop Illegal Mining in Madre de Dios,” InSight Crime, March 11, 2019, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/brief/peru-illegal-gold-mining

[lv] Miriam Wells, “Peru’s ‘Mining Mafia’ Seek To Legalize Their Operations,” InSight Crime, August 28, 2013, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/brief/perus-mining-mafias-seek-to-legalize-their-operations

[lvi] Katy Ashe, “Elevated Mercury Concentrations in Humans of Madre de Dios, Peru,” PLOS One, March 2012, vol. 7, issue 3, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033305

[lvii] Mac Margolis, “Gold Prices Cause Mining Boom That Threatens Amazon Rainforest,” The Daily Beast, August 19, 2011, https://www.thedailybeast.com/gold-prices-cause-mining-boom-that-threatens-amazon-rainforest

[lviii] Rhett Butler, “Environmental impact of mining in the rainforest,” Mongabay, July 27, 2012, https://rainforests.mongabay.com/0808.htm

[lix] Katy Ashe, “Elevated Mercury Concentrations in Humans of Madre de Dios, Peru,” PLOS One, March 2012, vol. 7, issue 3, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033305

[lx] “Mercury in gold mining poses toxic threat,” NBC News, January 10, 2009, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/28596948/ns/world_news-world_environment/t/mercury-gold-mining-poses-toxic-threat

[lxi] “Mercury in gold mining poses toxic threat,” NBC News, January 10, 2009, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/28596948/ns/world_news-world_environment/t/mercury-gold-mining-poses-toxic-threat

[lxii] Amanda Paulson, “Camp Amazon: Inside the ‘lungs of the Earth’,” Christian Science Monitor, September 24, 2018, https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/2018/0924/Camp-Amazon-Inside-the-lungs-of-the-Earth

[lxiii] “Amazon has nearly 100,000 km of roads,” Mongabay, December 8, 2012, https://news.mongabay.com/2012/12/amazon-has-nearly-100000-km-of-roads

[lxiv] Sadia Ahmed, et al., “Temporal patterns of road network development in the Brazilian Amazon,” Regional Environmental Change, October 2013, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 927-937, DOI 10.1007/s10113-012-0397-z

[lxv] Dan Collyns, “Roads are encroaching deeper into the Amazon rainforest, study says,” The Guardian, January 28, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jan/28/roads-are-encroaching-deeper-into-the-amazon-rainforest-study-says

[lxvi] Yvette Sierra Praeli, “The Amazon will reach tipping point if current trend of deforestation continues,” Mongabay, October 3, 2022, https://news.mongabay.com/2022/10/the-amazon-will-reach-tipping-point-if-current-trend-of-deforestation-continues

[lxvii] Liz Kimbroug, “Roads through the rainforest: an overview of South America’s ‘arc of deforestation’,” Mongabay, July 21, 2014, https://news.mongabay.com/2014/07/roads-through-the-rainforest-an-overview-of-south-americas-arc-of-deforestation

[lxviii] Liz Kimbroug, “Roads through the rainforest: an overview of South America’s ‘arc of deforestation’,” Mongabay, July 21, 2014, https://news.mongabay.com/2014/07/roads-through-the-rainforest-an-overview-of-south-americas-arc-of-deforestation

[lxix] Philip Fearnside, “Business as Usual: A Resurgence of Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon,” Yale Environment 360, April 18 2017, https://e360.yale.edu/features/business-as-usual-a-resurgence-of-deforestation-in-the-brazilian-amazon

[lxx] Orla Dwyer, “As much as half of the Amazon will face several ‘unprecedented’ stressors that could push the forest towards a major tipping point by 2050, new research finds,” Caron Brief, February 2, 2024, https://www.carbonbrief.org/unprecedented-stress-in-up-to-half-of-the-amazon-may-lead-to-tipping-point-by-2050

[lxxi] Phillip Fearnside, “Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science, September 2017, DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.102

[lxxii] “Amazon deforestation is close to tipping point,” Phys.org, March 20, 2018, https://phys.org/news/2018-03-amazon-deforestation.html

[lxxiii] Argemiro Teixeira Leite-Filho, Britaldo Silveira Soares-Filho, Juliana Leroy Davis, Gabriel Medeiros Abrahão & Jan Börner, Deforestation reduces rainfall and agricultural revenues in the Brazilian Amazon, Nature, May 10, 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-22840-7

[lxxiv] Chelsea Gohd, “New Study Shows Just How Close The Amazon Rainforest Is to The Brink of Collapse,” Science Alert, February 24 2018, https://www.sciencealert.com/deforestation-amazon-collapse-savannah-imminent

[lxxv] Lovejoy and Nobre, “Amazon Tipping Point,” Science Advances, February 2018, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2340

[lxxvi] Stephen Leahy, “The REAL Amazon-gate: On the Brink of Collapse Reveals Million $ Study,” February 104 2010, https://stephenleahy.net/2010/02/15/the-real-amazon-gate-on-the-brink-of-collapse-million-study

[lxxvii] Delphine Zemp, et al., “Self-amplified Amazon forest loss due to vegetation-atmosphere feedbacks,” Nature Communications, March 13, 2017, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14681

[lxxviii] Delphine Zemp, et al., “Self-amplified Amazon forest loss due to vegetation-atmosphere feedbacks,” Nature Communications, March 13, 2017, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14681

[lxxix] Lovejoy and Nobre, “Amazon Tipping Point,” Science Advances, February 2018, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2340

[lxxx] “Amazon deforestation is close to tipping point,” Phys.org, March 20, 2018, https://phys.org/news/2018-03-amazon-deforestation.html

[lxxxi] John Hollis, “Mason’s Thomas Lovejoy says the time to act for the Amazon is now,” George Mason University News, December 10, 2019, https://science.gmu.edu/news/masons-thomas-lovejoy-says-time-act-amazon-now

[lxxxii] Orla Dwyer, “As much as half of the Amazon will face several ‘unprecedented’ stressors that could push the forest towards a major tipping point by 2050, new research finds,” Caron Brief, February 2, 2024, https://www.carbonbrief.org/unprecedented-stress-in-up-to-half-of-the-amazon-may-lead-to-tipping-point-by-2050

[lxxxiii] Orla Dwyer, “As much as half of the Amazon will face several ‘unprecedented’ stressors that could push the forest towards a major tipping point by 2050, new research finds,” Caron Brief, February 2, 2024, https://www.carbonbrief.org/unprecedented-stress-in-up-to-half-of-the-amazon-may-lead-to-tipping-point-by-2050

[lxxxiv] Catherine Brahic, “Parts of Amazon close to tipping point,” New Scientist, March 5, 2009, https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn16708-parts-of-amazon-close-to-tipping-point

[lxxxv] Fred Pearce, “Rivers in the Sky: How Deforestation Is Affecting Global Water Cycles,” Yale Environment 360, July 24, 2018, https://e360.yale.edu/features/how-deforestation-affecting-global-water-cycles-climate-change

[lxxxvi] Peter Bunyard, “Without its rainforest, the Amazon will turn to desert,” Ecologist, March 2, 2015, https://theecologist.org/2015/mar/02/without-its-rainforest-amazon-will-turn-desert

[lxxxvii] “Stark Beauty: Images of Israel's Negev Desert,” Live Science, https://www.livescience.com/31372-israel-negev-desert-photos.html

[lxxxviii] “Forests Precede Us, Deserts Follow,” Uncommon Thought, 2015, https://www.uncommonthought.com/mtblog/archives/2015/02/04/forests-precede.php

[lxxxix] Jim Robbins, “Deforestation and Drought,” New York Times, October 9, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/11/opinion/sunday/deforestation-and-drought.html

[xc] Jonathan Watts, “Amazon rainforest losing ability to regulate climate, scientist warns,” The Guardian, October 31, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/oct/31/amazon-rainforest-deforestation-weather-droughts-report

[xci] Morgan Kelly, “If a tree falls in Brazil…? Amazon deforestation could mean droughts for western U.S.,” Princeton News, November 7, 2013, https://www.princeton.edu/news/2013/11/07/if-tree-falls-brazil-amazon-deforestation-could-mean-droughts-western-us

[xcii] “Tropical Deforestation Affects Rainfall in the U.S. and Around the Globe,” NASA, September 13, 2005, https://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/news/topstory/2005/deforest_rainfall.html

[xciii] Daniel C. Nepstad, “Interactions among Amazon land use, forests and climate: prospects for a near-term forest tipping point,” Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B, February 2008, pp. 1737–1746, doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.0036

[xciv] Amanda Paulson, “Camp Amazon: Inside the ‘lungs of the Earth’,” Christian Science Monitor, September 24, 2018, https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/2018/0924/Camp-Amazon-Inside-the-lungs-of-the-Earth

[xcv] Jake Spring, “Soy boom devours Brazil’s tropical savanna,” Reuters, August 28, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/brazil-deforestation

[xcvi] Philip Fearnside, “Business as Usual: A Resurgence of Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon,” Yale Environment 360, April 18 2017, https://e360.yale.edu/features/business-as-usual-a-resurgence-of-deforestation-in-the-brazilian-amazon

[xcvii] Jake Spring, “Soy boom devours Brazil’s tropical savanna,” Reuters, August 28, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/brazil-deforestation

[xcviii] Michael Hopkin, “Brazilian savannah 'will disappear by 2030',” Nature, July 20, 2004, doi:10.1038/news040719-6

[xcix] Jonathan Mingle, “The Slow Death of Ecology’s Birthplace,” Undark.org, December 16, 2016, https://undark.org/article/slow-death-brazil-cerrado-ecology

[c] Aline C. Soterroni, Fernando M. Ramos and Michael Obersteiner, “Fate of the Amazon is on the ballot in Brazil’s presidential election (commentary),” Mongabay, October 17, 2018, https://news.mongabay.com/2018/10/fate-of-the-amazon-is-on-the-ballot-in-brazils-presidential-election-commentary

[ci] Chris Fitch, “Deforestation causing São Paulo drought,” Geographical, February 5, 2015, http://geographical.co.uk/places/cities/item/761-deforestation-behind-sao-paulo-drought

[cii] Jim Robbins, “Deforestation and Drought,” New York Times, October 9, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/11/opinion/sunday/deforestation-and-drought.html

[ciii] “Brazil reveals plans to privatize key stretches of Amazon highways,” The Guardian, January 23, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/22/brazils-government-reveals-plans-to-privatize-key-shipping-routes

[civ]Aline C. Soterroni, Fernando M. Ramos and Michael Obersteiner, “Fate of the Amazon is on the ballot in Brazil’s presidential election (commentary),” Mongabay, October 17, 2018, https://news.mongabay.com/2018/10/fate-of-the-amazon-is-on-the-ballot-in-brazils-presidential-election-commentary

[cv] A Balancing Act for Brazil’s Amazonian States An Economic Memorandum, World Bank Group, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/brazil/publication/brazil-a-balancing-act-for-amazonian-states-report, p. xvii.

[cvi] Liz Kimbrough, “How close is the Amazon tipping point? Forest loss in the east changes the equation,” Mongabay, September 20, 2022, https://news.mongabay.com/2022/09/how-close-is-the-amazon-tipping-point-forest-loss-in-the-east-changes-the-equation